Dufferin County’s Jail

With the notable exception of inmates charged with vagrancy (more on this later), the vast majority of time served at Dufferin County Jail was measured in days, weeks or a few months.

Inside an Unusual Jail

In 1881, before Dufferin County’s new jail in Orangeville was even finished, two young boys became its first occupants when they stole materials being used to build it! It was an interesting beginning for an unusual jail.

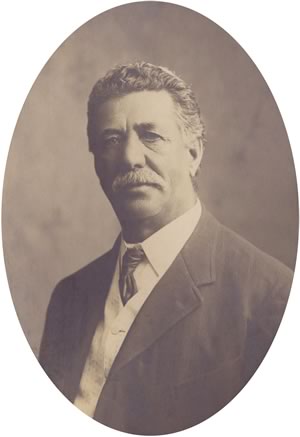

Charles Bowles, 1848–1925, was the jail’s turnkey at its opening in 1881 and became its longtime governor in 1894. Known as judicious, efficient and kind, he did much to establish the jail’s reputation for fairness and decency. Courtesy Museum of Dufferin P-1426I.

Special treatment for juvenile offenders was still years away in Ontario, but the constabulary opted for leniency and, after what they hoped was a good scare, set the two boys free. So the first official residents of the county’s 22 jail cells were two men from Richmond Hill. For stealing barrels of fish on display in front of a store on Broadway, they earned themselves a one-month stay.

A profile builds

The fish thieves soon had company. During their tenure and over the weeks following, the jail took in a number of vagrants, a larcenist, two farmers who refused to pay poll tax, a pair of men charged with assault (on each other, it seems), one “lunatik” [sic] and – always a sure bet – several inmates flagged as D&D – a wearily repeated entry in the records for drunk and disorderly. Thus at first it appeared that if year one was any indication, Dufferin County’s new jail was going to become a holding tank for regrettable, if fairly low-level, human frailty.

That image changed considerably late in 1881 when a cell door clanged behind Henry McCormick. In 1870 he captured national attention by fleeing a murder charge in Mulmur Township. Now, 11 years later, extradition from Michigan had brought him back to Orangeville where his case dramatically lifted the profile of Dufferin’s jail and the new courthouse that sat impressively in front of it. (He was convicted of manslaughter a few weeks later.)

The majority of inmates

The jail’s raised profile carried into 1882 when it took in a Shelburne man also charged with murder. He walked free with an acquittal, but his cell and others gradually filled with less newsworthy prisoners. Along with the inevitable D&D convictions that year, there were inmates serving time for assault (22), disorderly conduct (12), larceny (3), breach of the pharmacy act (2) and vagrancy (7). Except for three women among the seven vagrants, all the prisoners were men, including two jailed for abusive language, two for non-payment of wages and 16 for breach of a bylaw. The records also show inmates doing time for “failure to pay fine,” suggesting the offenders’ access to ready cash influenced who went to jail and for how long.

The punishment (mostly) fit the crime

With the notable exception of inmates charged with vagrancy (more on this later), the vast majority of time served at Dufferin County Jail was measured in days, weeks or a few months. It was not a facility like the famous Kingston Penitentiary, designed for multiple-year incarcerations. Over the century or so the county jail was in use, the longest sentences tended to be six months and even those were in the minority.

In the autumn of 1898, for example, an Amaranth man spent three weeks in a cell for defaulting on debts, and a young man from the same township spent just a few days, to cool down, the magistrate said, after threatening neighbours with a rifle when their daughter chose not to marry him. The only six-month sentence that fall was handed a Grand Valley hotelkeeper for liquor act violations. When he fled the county, a defence witness earned a week behind bars for refusing to reveal his whereabouts.

At the discretion of the court, a sentence to jail could be made more specific. Every inmate had to do general maintenance, but some, like the two men who stole barrels of fish, were sentenced to “hard labour.” That meant things like digging a well, splitting wood for winter and digging paupers’ graves in Greenwood cemetery.

Being local or not also had an effect, as a stranger learned in 1899. In the bar at Junction House in Cataract, he sold his winter coat for $2. When he took it off, he had another underneath. That one he sold for $2.50. When he was arrested in Charleston (Caledon Village), a third coat was found to have burglar tools in the lining. The coats were stolen in Orangeville and the stranger’s trial was in Orangeville, but his six-month sentence was spent at the notorious Central Prison in Toronto.

Still, being local was no guarantee of clemency. In 1894 an Orangeville man was convicted of indecent assault – on his stepmother. His sentence, which might have easily been accommodated in a Dufferin cell, was served at Central.

Jailing vagrants: cruel to be kind?

Newspapers in the county fell over themselves in July 1916 to tell the story of Martha McKitrick, formerly of East Garafraxa, who was being driven to Toronto (her first ride in a car) to live at the Aged Women’s Home on Belmont Street. What was the big deal? After spending 11 years in the cells of Dufferin County Jail on charges of vagrancy, Martha had come into a surprise $10,000 inheritance. And even more striking than her long stay is the story of George Lovell. In his obituary of March 1915, the Orangeville Banner reported Lovell had died in his cell after spending 37 years in jail on vagrancy charges.

Putting the indigent, the homeless and the disabled in jail was a thorn in the county’s side from day one. Unlike neighbouring counties, Dufferin never had a house of refuge, a poorhouse, so the county jail became the default placement. The impact of this policy was significant. For example, in the 1885 report there were 65 names on the inmate list, 39 of whom were held on the essentially harmless charge of vagrancy and two on the sad charge of being “lunatik.” (Four of the vagrants were under 14; six were female.) Ten years later, in a stinging editorial, the Orangeville Sun pointed out that of the 14 prisoners in the jail on May 2, 12 were vagrants. Numbers like those prevailed well into the next century. So did the stinging editorials.

The indignation expressed by every county newspaper primarily arose because many of the vagrancy prisoners were, like Martha McKitrick and George Lovell, essentially permanent residents. Yet the reality was that in Dufferin there was nowhere else to go, and to legally jail these unfortunate souls they had to be charged. (Notably, in Wellington County in 1876, a year before its house of refuge was built, over half the inmates in the county jail were there for vagrancy.)

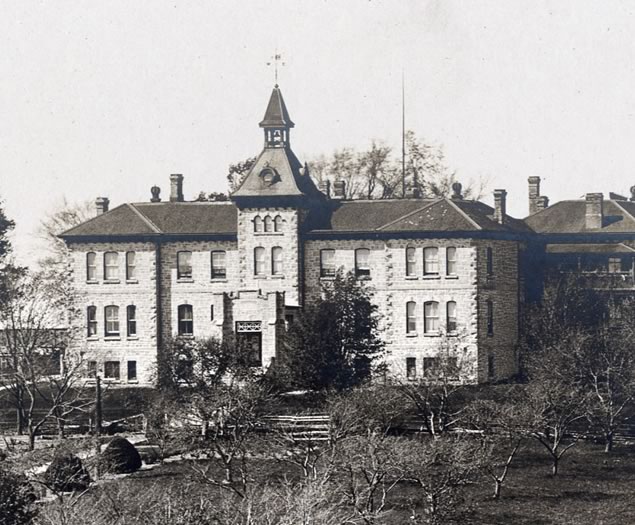

The walls of the Dufferin jail’s outdoor yard were built with an inward slant to prevent prisoners from scaling them. The slant can be seen in this exterior photo taken in 1986 after the jail was closed to be renovated to house municipal offices. De Ha Josef for the County of Dufferin.

A factor often glossed over is that Dufferin County Jail had a genuine reputation for treating prisoners fairly, reasonably and, in the case of vagrants, with kindness. The situation was an embarrassment to the county and leading citizens were certainly upset, but there is little evidence the vagrants either protested or complained.

Ultimately, a quite unusual jail

In keeping with the notion of a law-abiding society, provincial law in Ontario mandated that for a county to become officially established it first had to have a jail. Dufferin’s facility did its bit to meet the mandate but also distinguished itself in other ways. For one thing, over its century of duty it never held an execution, unlike its neighbours, Peel which had three, Wellington six, and Simcoe five. It did, however, host a wedding. In March 1898 Phoebe Hambly, in jail for, yes, vagrancy, married Austin Adams. The governor of the jail and his wife catered the wedding.

Related Stories

Behind the Scenes at Museum of Dufferin

Nov 20, 2018 | | HeritageWhat makes your old family heirlooms or bric-a-brac museum-worthy? It’s all in the story they tell.

A Tale of a Jail

Mar 21, 2010 | | Historic HillsWhen it came into service in 1867, built on land donated by the Village of Brampton, Peel County jail was a grim edifice modelled on England’s notorious Newgate Prison.

The Great Escaper

Mar 31, 2013 | | Historic HillsThe Orangeville Sun called him Robert the Bold. Local police called him ‘armed and dangerous.’ His neighbours called him ‘misunderstood.’ Bob Cook’s story fits all these descriptions – and then some.

A Place for the Deserving Poor

Jun 17, 2013 | | Historic HillsMales and females, including married couples, slept and ate separately.