A Forest is More Than Its Trees

From deep in the earth to high in the sky, forests shelter teeming life.

My shirt clings to my back as the midsummer sun pushes the temperature past 30C. I’m hiking the Dufferin County Forest Main Tract at 5 p.m. on July 17. Prime time for birdsong is early morning, but avian voices still ring out in the sweltering woods. Two male black-throated blue warblers call and respond, warning each other off. Each male guards a home territory containing the food and shelter necessary to attract females.

Black-throated blue warblers were not common in Headwaters during the time of the first Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Ontario project from 2001 to 2005. Since then, however, these dapper forest birds have increased here and elsewhere in southern Ontario. The reason is likely increased forest cover and the maturation of existing forests.

As I ramble onward, other forest birds also sing. The emphatic teacher-teacher-teacher of an ovenbird, another warbler species, resounds from the undergrowth. Somewhere among the mushrooms, tree seedlings and fading trilliums on the forest floor is the ovenbird’s unique domed nest. Its resemblance to an outdoor bread oven with a side entrance gave the ovenbird its name. So well concealed are these nests that in my five decades of birding I’ve found only one.

Red-eyed vireos call high above in the sugar maple canopy. These warbler relatives are champion vocalists. The late Ontario nature writer, Louise de Kiriline Lawrence, once counted 22,197 songs from a single male in a single day!

A wood thrush adds its voice to the modest symphony. Beautiful crystalline notes glide through green foliage backlit by the afternoon sun. I’m intrigued that the song of this bird can touch my heart, bridging the divide between bird and human.

More than trees

But what is this forest I’m hiking through? The pat answer is an expanse of trees. Not just one tree, or a copse, but thousands of trees covering a wide swath of terrain. And though you can’t have a forest without trees, a forest is much more than the oaks, pines, maples and basswoods contained within it. It is all the life that finds succour within its bounds: life underground, life on the forest floor, life on the trees themselves – on their bark, limbs and foliage.

Underground, a forest is a living community of mycorrhizal fungi entwined with tree roots in a nutrient-trading relationship that greatly benefits both trees and fungi. And among the fungal tendrils and tree roots is a subterranean city teeming with billions of inhabitants, from numberless bacteria to legions of ants, worms, grubs, millipedes and centipedes. All those invertebrates feed a host of small animals including moles, shrews and salamanders. Sustained not only by abundant food, but also by the moisture and humidity that prevails in the shade of the forest trees, salamanders are completely dependent on our forests. Most salamanders live a fossorial existence, wending their way through underground clefts, tunnels and fissures, and appearing only occasionally on the surface, notably for springtime breeding.

Above ground is a forest’s most obvious feature – its trees. Trees, through their size and height, multiply the sheer volume of habitat available for birds and animals. Meadows may teem with life, but a forest supports life in a biotic layer that can extend 20 or 30 metres upwards.

The pretty black-throated blue warbler has a reason to sing. It belongs to a species whose numbers have increased here in recent years. Photo by Robert McCaw.

Many birds, including nearly all in the appropriately named wood warbler group, need those trees. About 20 warbler species inhabit Headwaters. The common yellowthroat prefers open wetlands, and a few other species live in shrubby habitats, but the rest depend on forests in various stages of succession, from young trees to old growth.

Along with the ovenbird, those forest-dependent warblers include the Canada warbler, a species of special concern here in Ontario. (“Special concern” means a species is at risk of becoming endangered or threatened.) Even rarer is the cerulean warbler, a threatened species that requires large forest tracts for breeding.

Role of dead and dying trees

Through their long lives, forest trees sustain wildlife – and they continue to do so after death. Dead and dying trees offer much to birds, insects and mammals. “We need more dead wood in the forest,” says Laura Timms, an ecologist at Credit Valley Conservation. “Snags, dead trees and woody debris are one measure of the ecological integrity of forests.”

Kata Bavrlic, senior specialist with CVC’s watershed monitoring program, cites the valuable relationship between dead trees and woodpeckers. “Woodpeckers,” she says, “are ecosystem engineers, creating cavities in dead trees that are then used by many other organisms for roosting, breeding and food storage.” In large forest tracts, hairy woodpeckers and the impressive crow-sized pileated woodpeckers are the main ecosystem engineers. Flying squirrels are one of the many creatures that benefit from their construction projects, living in the holes created by these woodpeckers.

The value of dead trees doesn’t end when they topple. As trees decompose on the forest floor, they provide habitat for beetles, spiders, millipedes and many other arthropods. Fallen trees sometimes nurture seedling trees and are often called nurse logs. Hemlock and yellow birch often germinate on these logs. Ultimately, of course, fallen trees decompose entirely, but even then they contribute to forest health by enriching the soil.

The takeaway for landowners lucky enough to have forest on their property is to show dead trees some love. Leave them in your woodlands, whether upright or lying on the forest floor. To those concerned about the safety of leaving dead trees standing, Timms says conservation authorities will remove limbs and reduce a tree’s height, eliminating risk while leaving snags to satisfy the needs of wildlife.

Forests once dominated the Headwaters landscape. Now they occupy only 33 per cent of the Nottawasaga River watershed, and a little less than 25 per cent of the land in the Credit River watershed. Forest cover is even lower in the Grand River and Humber River watersheds, at about 19 per cent each. The good news for Headwaters, however, is that much of the remaining forested land in all four watersheds is found in this region – along the Niagara Escarpment, on the Oak Ridges Moraine and at Luther Lake in the Grand River drainage system.

Interior forests

Another metric is the amount of “interior forest” embedded in larger forests. Interior forests are at least 100 metres from the forest edge – removed from roads, buildings, farmland and the dry, windy conditions on the forest perimeter, as well as the predators that often lurk there. Interior forest patches provide vital habitat for forest birds, including several warbler species, and this makes their scarcity concerning. Only about 3 per cent of the Credit River watershed qualifies as interior forest. The Nottawasaga watershed, the most heavily forested in Headwaters, fares better, but only about 9 per cent of its forests are interior.

Larger forests, of course, contain more interior forest and this contributes to increased species diversity, says Yvette Roy, a CVC ecologist. Roy touts other attributes of large forests: “They contain a variety of habitat types characterized by trees of different ages and species. This overall habitat matrix can support a greater diversity of all sorts of animals. Invasive species are also less likely to be found within large woodlands.”

Hemlocks are late arrivals to the woodland, thriving in the rich moist soil of mature forests. Photo by Robert McCaw.

Fortunately Headwaters is graced with several large forests. The Dufferin County Forest Main Tract is one of the largest, at more than 600 hectares, or 1,500 acres. Other large Dufferin forests that feature interior forest habitat include Hockley Valley Provincial Nature Reserve, Mono Cliffs Provincial Park and Boyne Valley Provincial Park, as well as the Luther Marsh Wildlife Management Area in the Grand River watershed. In Caledon, Glen Haffy and Albion Hills conservation parks protect extensive forest habitat.

Though bigger is usually better when it comes to forests, every little bit helps. Timms even raises the intriguing idea that some small remnant woodlots may, in fact, contain old-growth trees. Timms defines old growth as trees older than 120 years. She wants to get out the message that private pro- perties may include old-growth forest containing rare plants. Conservation authorities can undertake inventories of private woodlots and offer management strategies.

Threats to forests

Threats to our forests include habitat loss, climate change and invasive species. Though most of Headwaters’ remaining forests enjoy some measure of protection, increasing urbanization is likely to affect them negatively. More people will probably lead to more forest disturbance. Even passive activities, such as walking a forest trail, can disturb sensitive birds and animals. Add off-leash dogs and free-roaming cats from nearby residences, and the effects escalate.

Climate change may happen too quickly for some of our tree species to undergo the genetic change necessary to adapt to warmer temperatures. And invasive species such as garlic mustard and buckthorn continue to displace native shrubs and wildflowers.

If we are wise, we’ll think carefully about how we can best manage these threats in order to sustain healthy forests far into the future. How far? Scott Sampson, manager of CVC’s natural heritage management program, takes the long view. “Forests can live for thousands of years,” he says. “Not the individual trees, but the forests themselves. They will endure for as long as we allow them to.”

Imagining the potential of Headwaters forests to endure for the coming millennia forces humility and makes it imperative for us to steward our forests with care, not only for the benefit of future human beings, but also for the wealth of fascinating life that depends, utterly, on their health.

Tell us your stories about urban wildlife:

Don Scallen is currently researching an article for this magazine on urban wildlife, and he’d like to hear from readers with stories to tell. Foxes, ravens and various species of hawks and falcons appear to be making themselves at home among us. Though Don may include some exceptional skunk and raccoon stories, he is particularly interested in hearing about some of the newer wildlife arrivals in our local towns. If you have a tale to tell, please contact him at [email protected].

Related Stories

These Flora and Fauna Rely On Forests

Sep 18, 2020 | | EnvironmentHere are six plants and animals, representative of myriad others, that depend completely on forests.

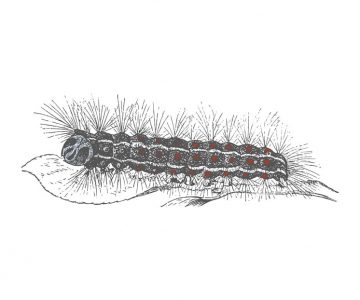

A Poetic Take on a Pest

Sep 18, 2020 | | EnvironmentCaledon poet Marilyn Boyle takes the gypsy moth caterpillar as her latest subject after her oak tree was decimated in the summer of 2020.

Where the Moose and the Elk Used to Roam

Mar 24, 2020 | | EnvironmentWildlife populations in Dufferin and Caledon have come and gone over the past few centuries, most dramatically since European settlement. Some species have vanished from the landscape. Others have arrived. Now things are changing again.

Fall’s Best: The Monarch Butterfly, the Porcupine and the Brook Trout

Sep 16, 2017 | | EnvironmentSavour fall with these 10 wonders of autumnal nature – from insects to constellations.

Invasive Species in Our Backyard

Jun 19, 2018 | | EnvironmentThey’re big. They’re strong. And they’re probably here to stay. But keeping them in check will give native plant species a chance.

How About Those Raptors (the Birds)?

Jun 20, 2019 | | EnvironmentLook up! Where eagles, hawks and vultures soar.

Meetings with Remarkable Trees

Sep 9, 2011 | | EnvironmentWe revel in their beauty, relax in their shade and are calmed by the soothing sound of their leaves soughing in the wind.

Take a Walk on the Wild Side: Forest Bathing

Mar 26, 2018 | | Good SportSlowing down, tuning in. With forest bathing, the slow movement takes to the woods.