Field of Schemes

There’s a population boom coming to Headwaters. Where will all the people go and what will it mean for our countryside?

Confession: I’ve made a good part of my living over the last twenty-odd years from the development industry. Now, before you write me off as another evil hustler out raping the countryside, bear in mind that my role has been that of a very tiny cog in a very large machine. A lowly civil engineering and planning techie, later doing economic development, I can put together a mean drawing, I know my way around a zoning bylaw, and my ability to yatter on at length about community branding – just ask the good folks of Shelburne – is truly frightening. I am, however, by no stretch of the imagination a land baron, and after checking with my wife, can confirm that I have yet to become rich from it.

It’s also true that I was born and raised on a farm in this area – one that has since been covered in a blanket of pavement and suburban-style houses, row-upon-row. What was once my manure pile is now someone else’s half-acre “estate.” Even though it has been nearly two decades since that happened, I still get a little wrench in my gut whenever I see it. All that’s to say that I have some appreciation for both sides of the growth debate.

In 2002, along with ten or so others, I was invited to take part in a round-table discussion with Brian Coburn, then minister responsible for rural affairs for the Ernie Eves Conservatives. Swept into the conference room by his handlers, Minister Coburn got to the point: “There will be two million new people in the Golden Horseshoe by 2021. Where are we going to put them?”

It wasn’t “if” these new people would arrive, it wasn’t that they “might.” They will.

Now, five or six years later, the planning horizon has been stretched to 2031. The official government estimate of population growth in the Greater Golden Horseshoe stands at 3.7 million new residents.

That’s one big mother of a subdivision. It’s like building a city the size of Oakville or Burlington every year for the next 23 years.

Back at that meeting in 2002, Minister Coburn tossed out what was then just the idea of a greenbelt, and asked us about transportation and providing employment and the really tough question: Is there some way to get these people to live outside the GTA?

The minister’s manner may have been confident, but there was something in his expression – and, as the guy responsible for figuring out what to do, who could blame him – of a deer in the headlights.

These days, it seems provincial planning legislation is popping up faster than weeds in a vacant lot. In 2002, the Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Plan was approved, and since taking office in 2003, the McGuinty Liberals have stayed at it: The Greenbelt Plan and a new Provincial Policy Statement in 2005, and the Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe in 2006.

Altogether it has turned planning in Headwaters into something like one big kid with ADD. Town planners in the region are faced with the administration of a vast array of new rules and regulations intended to protect our tender bits and encourage growth in those areas where, in the wisdom of modern planning science, it can be accommodated.

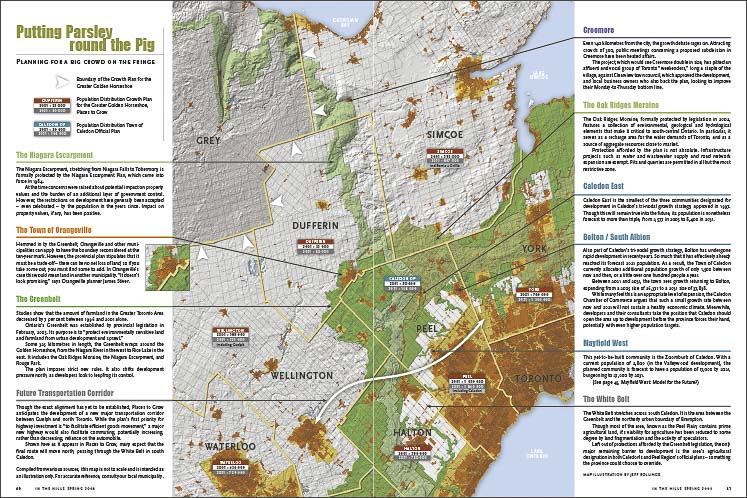

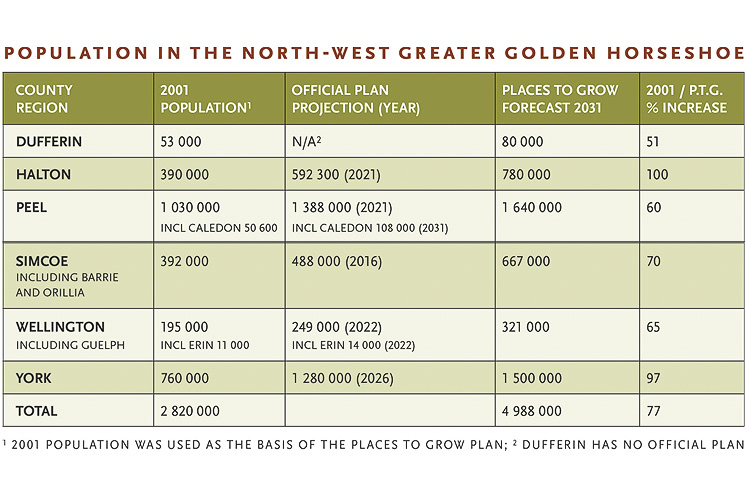

Projection for population growth in the north-west Greater Golden Horseshoe

Of particular note these days is the Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe, or Places to Grow. The plan and accompanying legislation has won three major awards from Canadian and American planning associations. Among other things, it decrees future population levels on a regional basis. Municipalities, which exist at the pleasure of the province, have no choice but to amend their local official plans to suit these targets.

Okay. So it looks as though, like it or lump it, we’ve got all these people coming for an extended visit. Just like that time your brother turned up unannounced with his new girlfriend and her eight kids from a previous relationship, you scramble to find some place for everybody to sleep, get them some food and drink, and break out an extra roll of toilet paper for the bathroom.

In effect, that’s what local planners are doing these days. The Places to Grow legislation dictates population figures for upper-tier municipalities only. So, for example, we know Dufferin is expected to take an additional 27,000 people. It is left to Dufferin and its constituent lower-tier municipalities to allocate who gets what.

This is particularly complex in Dufferin’s case, because it is one of only two counties in Ontario with no official plan, and no county planning function. So planners in each of Dufferin’s lower-tier municipalities have been conducting studies to determine how much population growth they think they can, at maximum, accommodate.

They are expected to absorb a good deal of it through “intensification.” The province has legislated that all regions and counties must accommodate a minimum of 40 per cent of new residential development within their existing built-up areas, as they existed when the plan came into effect in June, 2006 – and they have until 2015 to phase it in.

Simply put, the idea of intensification is that by packing more people into the existing urban areas, less land will be chewed up by new development. Upping urban population densities is thought to have other benefits, too, such as stimulating downtown revitalization and making provision of infrastructure more affordable.

It all sounds impressive, until you consider the flip side of the 40-per-cent rule: that means 60 per cent of new development will continue to be “greenfield” – nibbling away year after year at the rural landscape. “No one has really picked up on that,” says Orangeville planner James Stiver.

Intensification makes a lot of sense, especially in large, highly serviced urban centres where they can build skyscraping complexes like those now going up in Mississauga. But the concept can prove trickier in rural communities. In the Town of Mono, for example, planner Mark Early told me he has generously assumed that one in five existing dwellings will have a basement apartment, despite the fact they aren’t currently permitted at all.

Still, by really packing them in, Dufferin planners think, all told, they might be able to accommodate 24,500 people in Dufferin. Pretty good, given the 27,000 target.

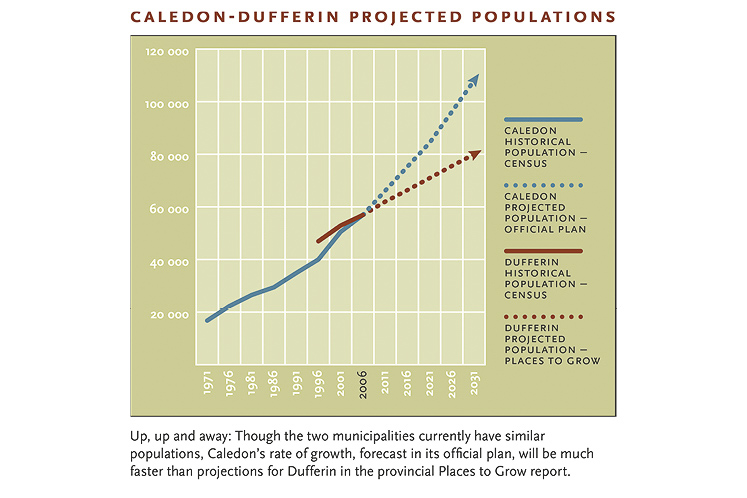

Projected population for Caledon-Dufferin

Where it all comes apart, however, is with infrastructure, which was not considered, in either the Places to Grow allocations or the estimates planners prepared. The province has directed that new development must be on full municipal services. Intended to discourage estate subdivisions, this requirement will place pressure on those communities with sewage treatment plants. In Dufferin, that’s Orangeville, Shelburne and Grand Valley. Both Shelburne and Orangeville are already approaching the maximum capacity of their respective receiving streams.

When servicing is factored in, the planners think that Dufferin’s capacity for new population is reduced to only 3,896.

Recognizing they need some help, Dufferin’s municipal officers have come together to work with the Ministry of Public Infrastructure Renewal, which oversees the Places to Grow Plan. Together they have taken steps to hire a consultant who will review the individual planner’s studies and attempt to formulate a growth management strategy for the county overall, juggling the numbers to try to meet the Places to Grow requirements, despite what appears to be a huge gap.

Along the way, it is hoped that the ministry will see the light: that Dufferin simply has neither the physical or social infrastructure needed to support such growth. Either the target needs to go down, or major investments in infrastructure will be required, but something’s got to give.

In outer-ring municipalities (those beyond the Greenbelt) such as Dufferin, the minister does have the option of permitting alternative intensification levels within built-up areas. However, when compared to neighbouring regions, the county already gets off easily as far as overall growth goes.

For example, where Dufferin’s population is set to increase by 51 per cent between 2001 and 2031, Halton Region’s is expected to double.

When I asked Orangeville’s James Stiver about this, he said, “As this study unfolds, it’s going to become clear that growth will have to occur in Orangeville, Shelburne and Grand Valley. There will have to be some annexation and increases in infrastructure.”

One possible solution for Orangeville would be a “big pipe” from Lake Ontario. In Caledon, Bolton is already hooked up, getting its water and sending back sewage to Lake Ontario and, due south of Orangeville, the Mayfield West development will do the same. Stiver favours the big-pipe solution; however, connection to a lake-based water system through the Greenbelt is currently prohibited.

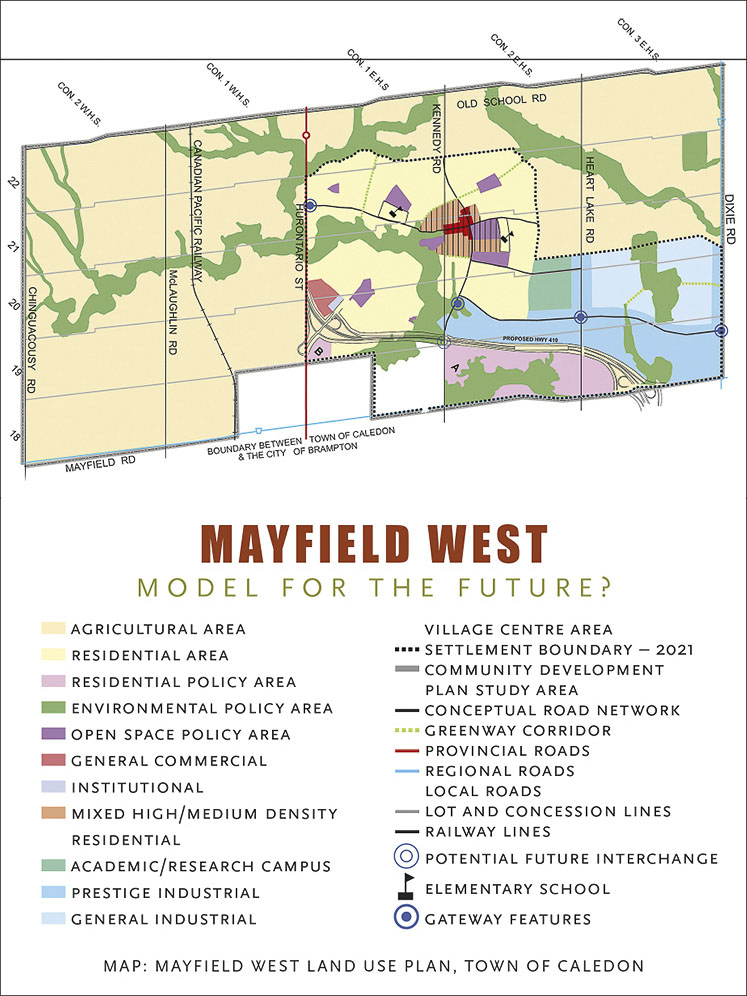

Mayfield West Land Use Plan

What will happen in Orangeville if servicing capacity is not expanded and the town remains hemmed in by the Greenbelt? For one thing, Stiver predicts, “Affordability will become a huge issue. Demand will keep going up, but there will be no supply.”

Like Dufferin, Peel is undertaking a similar allocation process. Peel is slated to receive 610,000 new residents – an increase of 60 per cent from the million or so that lived there in 2001. Caledon’s proposed official plan anticipates a 2031 population of 108,000 – nearly double its current population. That figure combined with Brampton’s and Mississauga’s current built-out projections still leaves the region 30,000 short of its Places to Grow allocation.

While the two cities undertake intensification studies to accommodate the surplus, Caledon is standing pat. Its tri-nodal growth strategy already directs population increases into three specific areas (Bolton, Caledon East and Mayfield West). Beyond that, says Mary Hall, the town’s director of planning and development, “I don’t believe Caledon will get a lot out of intensification.”

“A worst case scenario,” she says, “is that there will be unallocated population that has to come to Caledon.” Then it will be a question of how big the number is. “If it’s 10,000 short, the town will have to review where it goes,” she says. “We’ll know by the end of the year.”

Overall, Hall sees the maze of planning regulations that now governs large parts of Caledon as a good thing. “They definitely assist with preventing sprawl,” she says. “We can’t stop growth, but we can manage it.” Still, she acknowledges, “What you end up with is all these situations where people on one side of the road are subject to different rules than people on the other, with no apparent reason. There will have to be some harmonization.”

All right, so there are a few issues to work out, but once everything has settled down, with all those new people sharing the burden, at least services will be better and cheaper and taxes will be lower. Right?

Not necessarily, say an increasing number of critics of the “grow-or-die” mantra that has characterized municipal planning for decades.

Former Orangeville councillor turned Green Party candidate Rob Strang is among them.

“As people move up here, the expectation is that the level of service will rise,” he says. Instead, he argues, what too often happens is that schools become more crowded, health and social services become overburdened, taxes rise and commute times increase.

He notes that roads are a particular burden on capital. “While development charges may pay to build them in the first place, they have to be rebuilt every twenty to thirty years. When I was on council we had to borrow fifteen million dollars, and most of it was for roads.”

His analysis seems borne out by the situation in Peel, which currently receives about 34,000 new residents each year. Like other large urban municipalities, the region is pleading very publicly with the province for help in providing social services and dealing with poverty. Regional chair, Emil Kolb, issued a news release in January containing some remarkable statistics that show just how hard Peel is struggling with growth-related issues. One example: the current average waiting time for social housing in Peel is twenty-one years. (Even though, for instance, the per capita taxes collected in urban Mississauga average more than 40 per cent higher than in rural Erin.)

Mono’s Mark Early raises similar concerns about Places to Grow. “The social link is missing,” he says. “There are no doctors now. Will we have to build another hospital?”

And it’s not just the social and economic impacts of growth that raise concern. In his 2007 annual report, Ontario’s environment commissioner, Gord Miller, also weighed into the debate with some strong challenges to the provincial planning process. Declaring that, “We keep saying that we want our cake, but we can’t stop eating it,” he highlighted “irreconcilable differences” between competing priorities.

“The 2005 Provincial Policy Statement states that preserving wetlands, significant woodlands and agricultural lands are priorities, but it also asserts that the construction of highways, the removal of aggregates, and the building of pipelines for water supply are priorities.”

The result of this bipolar approach, Miller claims, is a process which automatically sets development proposals off on a course toward approval, without first questioning the fundamentals: Do we really need this? Can we sustain it? At its worst, the process can turn municipal planners into application-takers and certificate-issuers, rather than big-picture folks who are contemplating where our communities are headed.

By way of illustration, Miller notes that Places to Grow dictates population growth without considering the carrying capacity of the receiving communities. What are you going to do when the aquifer dries up? Well, as Caledon has done and Orangeville dreams of, you’ll most likely put in a big pipe.

Says Miller: “The province’s approach fails to allow for the possibility that significant population growth may simply be inappropriate and ultimately unsustainable in some communities, because of ecosystem limitations. To artificially expand the carrying capacity of these communities – through the long-distance transport of water and wastewater – will certainly create systems more vulnerable to disruption and even less self-sufficient. In addition, it will greatly increase the challenges and complexity of protecting ecosystem integrity in the Great Lakes Basin and the Greater Golden Horseshoe.”

As for the lofty environmental goals so carefully set out in the Greenbelt, the Oak Ridges Moraine and Niagara Escarpment plans and elsewhere, the same I-really-need-to-see-someone-about-this-dual-personality situation exists. On one hand, these plans all loudly proclaim the need to preserve wetlands and wildlife and farmland. On the other, transportation and infrastructure projects are largely exempt from their control. These will be required in significant number to serve an expanded outer-ring population. Hard to see how a 400-series highway preserves farmland.

For example, Miller points out the Niagara Escarpment Plan “allows new pits and quarries in the largest land use zone with an amendment to the plan and, to date, every application for a new or expanded operation has been granted.”

So the plans and the perspectives are plentiful. And there is some comfort in the fact that Queen’s Park has taken some belated but bold initial steps to rein in sprawl. Even so, the planning horizon extends only to 2031, and no one is saying what happens after that.

Furthermore, the whole shooting match – the Greenbelt Plan, Oak Ridges Moraine Plan, the Niagara Escarpment Plan and the Places to Grow allocations are all open for review by 2015.

“If it was all part of a plan that at some point conceives of the need for populations to level off, it wouldn’t be so frightening,” says Rob Strang. “But right now it’s just another step in an ongoing, seemingly endless population expansion that’s just not sustainable.”

In the meantime, spare a thought for our conflicted municipal planners. Awash in a field of schemes, busier than Dalton McGuinty at charisma school, they’re doing their best to roll out the cots, cook supper, unplug the toilet and protect the good dishes, all at the same time.