Yesterday’s Superstore: A Tribute to the Old General Store

In the Waldemar store, pop was five cents in the 1940s (seven cents if you took it outside, but there was a two-cent bottle return).

The store was full of things they really needed: sugar, flour, horse liniment, bolts of cloth, shoe polish, canned goods, hinges, nails, tools, mason jars, soda pop, castor oil, tire patching kits, pickling spices, mouse traps, cheese, kerosene, tobacco, Epsom salts and the like. Photo by Pete Paterson.

There was a time when every community had its mill, its church, a blacksmith shop and a tavern or two, but the general store was its heart and soul. Part retail outlet, part trading post and part meeting place, the old-fashioned general store was a centrepiece of community life.

In 1902, John Groskurth took over the general store in Waldemar, northwest of Orangeville, and ran it for almost fifty years, but it wasn’t until 1930 that he finally put up a sign. That was the year he became the village postmaster. With the post office now in the store, the poobahs in Ottawa required that it have a sign, so they sent him one – with his name spelled wrong!

Such bureaucratic fumbles, however, meant little to the citizens of Waldemar and surrounding Amaranth Township. What mattered was that, along with the post office, the store was full of things they really needed: sugar, flour, horse liniment, bolts of cloth, shoe polish, canned goods, hinges, nails, tools, mason jars, soda pop, castor oil, tire patching kits, pickling spices, mouse traps, cheese, kerosene, tobacco, Epsom salts and the like.

Equally important, John Groskurth was someone they knew. He was honest and he was reasonable about things like bartering and granting credit. Moreover, he lived right in the store, so if a farmer out on the 8th Line had a really sick cow, he could get raw linseed oil or Dr. Bell’s Medical Wonder in the middle of the night.

Like every general store in every community throughout these hills, the one in Waldemar didn’t need a sign.

“The first thing we built was the store”

From Canada’s earliest days, a general store was essential to the survival of a new settlement. When Champlain founded Québec in 1608, he noted in his journal that “The first thing we built was the store.” More trading posts than retail centres, the early stores provided the basic supplies so crucial if a nascent settlement was to grow. Over time these posts became true general stores, lending identity and focus to a community.

From Canada’s earliest days, a general store was essential to the survival of a new settlement. When Champlain founded Québec in 1608, he noted in his journal that “The first thing we built was the store.” More trading posts than retail centres, the early stores provided the basic supplies so crucial if a nascent settlement was to grow. Over time these posts became true general stores, lending identity and focus to a community.

Here in the hills, which did not open up to settlement until the nineteenth century and where the main attraction was land for farming, new settlements first developed around mills, sawmills and gristmills, but these new settlements didn’t become real communities until they had a general store.

Bolton, for example, grew more rapidly once George Bolton opened a store in an oversized log cabin after his uncle James had built a mill in the early 1820s. In what would one day be Orangeville, James Griggs had built a pair of mills, well before Orange Lawrence got there in the late 1840s. But Lawrence, the putative father of Orangeville, put up a general store and the town grew.

Similar mill-then-store sequences were repeated in Grand Valley, and Erin where, in 1826, the Trout family built both a sawmill and a store. And probably no one was more sensitive to the mill/store relationship than Lewis Horning. In 1830 he bought 2,500 acres from the Crown and, at age 67, led a party (including his fourteen children) into the bush to build the village of Horning’s Mills – everything at once: mills, store, and homes.

Shelburne, though, was an exception to this phenomenon. There was no water power there to attract millers, but when the town got its start in the 1860s the railroad was soon to arrive. Steam power was taking over and, to boot, the new settlement was blessed with the far-sighted entrepreneur, William Jelly, as well as a merchant prince in the person of Edward Berwick. In fact, the pattern of business development in Shelburne illustrated the way stores in larger communities moved from general merchandising into specialization.

Like other major centres in the hills, Shelburne acquired sufficient population to support separate, specialized enterprises including jewellers, milliners, hardware stores and so on. The town simply outgrew the “everything store.” Not that there wasn’t still a bit of mix and match. In 1916, at Rutledge and Husband, for example, specialists in pianos and organs, you could also buy sewing machines. And gravestones. And life insurance!

Like other major centres in the hills, Shelburne acquired sufficient population to support separate, specialized enterprises including jewellers, milliners, hardware stores and so on. The town simply outgrew the “everything store.” Not that there wasn’t still a bit of mix and match. In 1916, at Rutledge and Husband, for example, specialists in pianos and organs, you could also buy sewing machines. And gravestones. And life insurance!

Outside the larger towns though, in the hamlets around the hills, the general store, often along with a church, was the foundation of their existence. Usually a store was built at the intersection of key roadways or in a spot far enough from larger towns to warrant the need for a supply base. Marsville in East Garafraxa, and Masonville and Redickville in Melancthon Township are examples. In these tiny settlements the general store endured in its traditional we-sell-everything form. However, these stores and their hamlets were the first to shrink and even disappear as time and modern technology marched forward.

“If you need it, we have it.

If we don’t have it, we’ll get it.

If we can’t get it, you don’t need it!”

“If you need it … etc.” was popular advertising hyperbole used by many general stores in their heyday. Still, the inventory held in a typical general store was mind-boggling (and the storekeeper always knew where everything was.) It had to be extensive because delivery time was anything but an overnight affair.

Usually a merchant waited for the arrival of a “traveller,” the representative of a wholesale supply house who would take orders for specific goods. But often days, even weeks might pass before an order was filled, especially for something out of the ordinary, for inventory at supply houses was very much limited to the tried and true.

Ira Eby and his wife Mary Ann (c.193o) in the store he ran in Horning’s Mills for thirty-five years. Local history has it that a friend and supplier in Toronto delivered goods to the store by airplane – perhaps one of the reasons the store continued to provide “almost everything,” even after automobile travel made it easy for villagers to drive to bigger stores in Shelburne. Photo Courtesy Dufferin County Museum And Archives.

The vagaries of weather and road conditions might also extend a delay. Once the railroad came to the hills almost all orders were dropped off by train at local stations, but getting the goods to a community such as Mono Mills, which had no station, meant that heavy snowfalls and spring mud held things up.

One consequence of the huge inventory in some stores was very dim light. For sheer lack of space goods were piled on window ledges or hung from the sashes. Another consequence was narrow aisles, because the inventory simply outgrew the shelf space, even though the shelves went right up to the ceiling. Clerks either used rolling ladders or became adept at knocking down items with a long-handled pick – and catching them.

“Store owners were faithful suppliers,” says Eddie Bolen, whose uncle worked briefly in Creemore and Hillsburgh before opening a general store of his own in Grey County. “By the second big war, practically everybody was farming with tractors, but there were still a few with horses and Uncle Jack kept harness around just for them. He didn’t have space for it and it didn’t make financial sense, but that’s what being a general storekeeper was all about: looking after your customers.”

That certainly was true in Mono Centre. “Harness parts, stove pipes, rubber boots, fishing gear and a huge wheel of cheese in a glass case. That’s what I remember,” says Sheila Woodall whose parents, Stan and Dorothy Thompson, owned the Mono Centre general store in the 1950s.

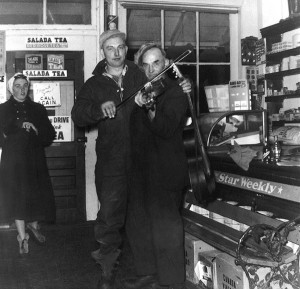

General stores were welcome places to gather and chat or play cards. At the Waldemar store, Jack Lomas and Billy Miller are about to offer a bit of music in front of the Star Weekly bench as Doris Miller looks on. Photo Courtesy Waldemar Tweedsmuir History.

“And cold meat sold by the slice,” she adds, “and a lot of tinned fruit and vegetables, epecially in winter. Most people had big gardens and grew their own, so tinned goods were not a big item in summer and fall. But that was canning time, so we sold materials for pickling and a lot of sugar and salt. Under the long counter there were bins full of them; almost everything was sold in bulk. Outside in the horse shed there were salt blocks and feed. Binder twine was there too, every July and August.”

Sheila also remembers the cellar at the Mono Centre store. “It’s a wonderful pub these days, but I hated it then. We stored rope and chain there. I didn’t mind selling that because each size was fed into the store through a hole in the floor so you just had to pull it up. But when a customer came with an empty whiskey bottle for ten cents worth of kerosene or naptha, you had to go down into the darkness and spider webs to get it!” (Sheila admits that whenever she could get away with it, she’d delegate the task to her younger, taller sister.)

Over in Waldemar, at John Groskurth’s store, the inventory and storage was similar. Beth Cleave, John’s granddaughter, also remembers the great wheel of cheese, and the bins of sugar, salt and rolled oats under the counter. And the nails in bins and barrels that had to be pulled out by hand into a scoop to be weighed.

“Grandpa was so good at figuring out just how much a customer wanted,” says Beth. “One person would say ‘one pound’ while another would make a shape with her hands and say, ‘oh, about this much’. He’d get it just right, and then – this was always something to see – he’d wrap it so neatly and with so little effort!”

“Grandpa was so good at figuring out just how much a customer wanted,” says Beth. “One person would say ‘one pound’ while another would make a shape with her hands and say, ‘oh, about this much’. He’d get it just right, and then – this was always something to see – he’d wrap it so neatly and with so little effort!”

In a typical general store, string was pulled from a cone fixed to the ceiling, but not before brown paper – just enough – came off a huge roll at the side of the counter and was expertly folded around the merchandise.

“In a way, it was like magic,” Beth remembers. “Somehow his fingers would bend the paper just so, wrap the string, tie a knot, snap it off and just like that, the package was ready. And he did it without looking!”

She adds, “Also without wasting anything.” Today’s recyclers would appreciate her point. “Even used envelopes would become paper for making lists or for figuring out somebody’s bill. No, there wasn’t any waste in the store. And the same was true of the customers. They saved the wrapping. I bet every house in Amaranth had a ball of used string.”

Getting the mail and gassing up

Like John Groskurth’s store in Waldemar, many a general store also served as the local post office. It was a “win-win” combination. Canada Post knew it would have a centralized local depot that was always open (except Sundays) run by a reliable, business-minded person. In turn, the storekeeper got an extra, often crucial, source of income, and people were drawn into the store.

Like John Groskurth’s store in Waldemar, many a general store also served as the local post office. It was a “win-win” combination. Canada Post knew it would have a centralized local depot that was always open (except Sundays) run by a reliable, business-minded person. In turn, the storekeeper got an extra, often crucial, source of income, and people were drawn into the store.

And because these post offices served several rural routes, there was opportunity for free delivery service. This often happened at harvest time when rural customers were too busy to get to town, even for “urgent” necessities. “Tobacco,” remembers Merle Still, who frequently drove a route out of Waldemar. “I’d be sorting out my delivery and a call would come in for tobacco. Somebody had to have his chew!”

Occasionally, a customer would take liberties with such generous service, like the gentleman in Chinguacousy Township who tended to abuse his line of credit. He would inch his aged car home on “Empty,” then have the rural mail driver bring a gallon of gasoline from the store in Sandhill – on credit – so he could get to town.

Adding gasoline to their inventory was one of the continuing adaptations practised by general storekeepers. Soon after the affordable Model T was introduced, many stores added a gravity-feed gasoline pump out front, and brands like BA (British American), White Rose and Supertest became household names.

On the other hand, “gassing up” rarely included the legal sale of liquor, although it was available in earlier times. A man named Sterne took over George Bolton’s store in the late 1830s and not only sold general goods, but ran the post office and offered whiskey produced in his well-respected distillery. However, it wasn’t long before Ontario’s powerful temperance movement combined with prohibition laws to take liquor out of stores across the province.

Good pay, bad pay, slow pay

“Wilbert, we’re going to have to sell this store before you give it away!”

“Wilbert, we’re going to have to sell this store before you give it away!”

Whether the wife of Wilbert Donaldson, a former owner of the Mono Centre store, actually said this, it is accepted truth in the village, and easy to believe by anyone with experience in retail. Mr. Donaldson apparently extended credit readily and found it very difficult to ask for what he was owed.

That pattern was almost universal among general store owners. In part, because of their small and defined customer base, merchants knew it could be counter-productive to have a reputation for being “tough on credit.” And in part, it was the inevitable flipside to the comfort of doing business in communities where just about everyone was acquainted with everyone else. It was a rare general storekeeper who could not address every customer by name, or who failed to inquire about a family member who’d left to work in the city or perhaps gone west on a harvest excursion. A local merchant always knew if a customer had recently been ill or bereaved or was planning to hold an auction sale. Such personal knowledge about their customers made it hard for storekeepers to ask for money.

In rural areas especially, it was difficult to collect debt because of the seasonal nature of farm income. Storekeepers were used to hearing “as soon as I ship the hogs” or “once the weather warms and the hens start laying again I’ll have the egg money for you.” For most merchants, credit was also a matter of emotional balance. The majority of customers duly paid, but the minority who were “bad pay” or “slow pay” could generate a level of frustration that was out of proportion to their actual debt, especially because few store owners charged interest.

Far too often these were the same customers who crossed the line in other ways. Former CBC home economics specialist Kate Aitken reported the story of a customer who paid a debt at her father’s store with a firkin of butter that had a heavy stone hidden at the bottom. (Kate’s father later returned the favour by concealing the stone in a bag of flour.)

Pilferage – shoplifting – was an occasional issue, but it usually involved inexpensive items. In the Waldemar store, pop was five cents in the 1940s (seven cents if you took it outside, but there was a two-cent bottle return). It was kept cool in the cellar – electricity didn’t reach the village until 1950 – and as Beth Cleave relates, “There were a couple of characters, only a couple, who’d ask for pop and then snitch a chocolate bar when Grandpa was in the cellar. But he knew who they were and it didn’t happen very often.”

Pilferage – shoplifting – was an occasional issue, but it usually involved inexpensive items. In the Waldemar store, pop was five cents in the 1940s (seven cents if you took it outside, but there was a two-cent bottle return). It was kept cool in the cellar – electricity didn’t reach the village until 1950 – and as Beth Cleave relates, “There were a couple of characters, only a couple, who’d ask for pop and then snitch a chocolate bar when Grandpa was in the cellar. But he knew who they were and it didn’t happen very often.”

Most stores kept high-value items, such as watches, jackknives and fountain pens, in ornate curved-glass cases. However, at R.W. Burrell’s general store in Caledon East (run by the same family for almost ninety years) “R.W.” may have had the ultimate solution to pilferage: he sat on a raised platform in the middle of this very full-service enterprise, from where he was able to keep a sharp eye on things.

All good things pass

In 1887, Fred Haines built a solid brick building in Cheltenham to house a general store. It was a good investment because general store trade was still years away from its peak. Then in 1917 one of the store’s customers, Frank Lyons, swapped a team of horses for a used Chevrolet. On the surface the transaction seemed unrelated to the village store; however, his Chevrolet meant Frank could easily go to Brampton to shop. For the old time general store, the arrival of the automobile signalled the end was coming.

There were other factors too that brought the era to a close: a decline in rural population reduced the customer base; an increase in government regulations took away the curbside gas pumps and removed profitable but potentially hazardous goods (such as cyanide for pest control) from the shelves. Groceries and fresh food became more closely monitored under new hygiene codes. And merchandising was changing.

In the early 1940s, people from miles around Orangeville drove to town just to see a new phenomenon at the Dominion Store: self-serve shopping. They stayed to buy. Sheila Woodall remembers her mother selling a woman a single item in the Mono Centre store late on a Saturday night in the 1950s and then wondering sadly whether it was “just something she forgot to buy in Orangeville.”

Today the Mono Centre store is a popular restaurant and Waldemar’s store is an attractive private home, but not all our general stores have disappeared. Cheltenham still has one and so does Inglewood (and they still have post offices, though the rural routes are gone) – but you won’t find horse liniment or harness parts in the inventory. Those staples of the working farm have been replaced by crafts and gift items in many of the local stores – which count on tourist traffic to bolster the income they earn from serving the local community’s need for milk and eggs and Aspirin.

Still, sometimes things come full circle. A few years ago, the Honeywood general store in Mulmur reinstalled hitching posts for horses – to serve the area’s recreational trail riders.

The General Store: Re-Imagined for the 21st Century

By Signe Ball

Lynda and Ian Wookey upgraded the Hockley Village General Store while maintaining its historic role as the village meeting place. Photo by Pete Paterson.

The past fifty years have been a hard slog for the few general stores that remain in the Headwaters region. Squeezed by chain convenience stores on one side and super-sized supermarkets on the other, independent village general stores have had a tough time competing. But curiously, the very population influx that at first spelled hard times is now providing a niche market as the demographics of the countryside evolve.

At the north end of the region two stores in particular have grabbed hold of the trends. And both of them strike a friendly balance between serving the local community and catering to day trippers and commuters en route to ski and cottage country.

Ian Wookey has spent summers and weekends at his family’s Hockley Valley property for thirty-five years. And he has fond memories of bicycling to the Hockley Village general store for ice cream. It was the “heart and soul” of the village, he says, “the place where neighbours met to have a coffee, buy a butter tart and pick up the newspaper.”

When the store came up for sale a few years ago, Ian, a Toronto developer, couldn’t resist what he knew would be, more than anything, “a labour of love.”

“I had this idea of something like Sam Drucker’s general store on Green Acres, with everything from soup to nuts, string to hose – and sawdust on the floor, I would have really liked that,” he says.

But the sitcom-inspired fantasies were not to be. The old store was in such poor repair that Ian eventually stripped it back to its post-and-beam skeleton and rebuilt and expanded it into an airy (and sawdust-free) emporium that now includes a café and a liquor store. (Ian acknowledges the latter provides a significant boost to the economic viability of the whole enterprise).

The complex of buildings on the site includes art studios and the Hockley Valley Brewing Co., though the brewery will be decamping to larger premises in Orangeville this spring.

Ian also had to give up his dream of stocking hardware (“You can’t compete with big box stores”), but the store does boast a wide variety of grocery staples and specialty foods.

Ian’s wife Lynda sources fresh organic greens and frozen meats, as well as a broad array of eco-friendly household products and stylish kitchenware. And there’s a good selection of store-made fresh or frozen prepared foods, including shepherd’s pie, chicken pot pie and soups.

Ian also made sure to retrieve the old store’s famous butter tart recipe – and they remain a favourite on the menu of the café – where locals continue to gather and gab, as they have for a more than a century.

At Rosemont General Store, Russell and Pam Stewart emphasize locally sourced “comfort foods” that appeal to the time-stressed, but health conscious and eco-aware residents of the modern countryside. Photo by Pete Paterson.

A little further up the concession, the Rosemont General Store, in operation since 1846, has also adapted to the changing times.

Proprietors Pam and Russell Stewart took over the store about eight years ago. For the first few years they experimented with gift items and equestrian supplies to supplement the groceries. Now, though, they are concentrating on food – the kind of food that meets the demands of the time-stressed, but also health-conscious and eco-aware customers of the modern countryside.

The offerings put an emphasis on locally sourced “comfort foods,” says Pam, who then reels off some of the temptations. They include frozen prepared foods such as store-made lasagna, cabbage rolls and soups, along with farm-fresh eggs, daily fresh-baked bread and free-range, hormone-free chickens. There’s Cookstown organic greens, Debra’s chocolates, Laura’s Luscious Desserts (made by Mono councillor and pastry chef Laura Ryan), and jams put up by store neighbour Dorothy Jane Needles.

And there’s always a fresh pot of Rosemont Dark, Creemore Fair Trade Coffee, ready to serve.

More Info

Dufferin County Museum Celebrates the General Store

The nostalgia-inducing goods pictured on these pages are all part of the extensive General Store Exhibition at Dufferin County Museum and Archives throughout this year.

The museum’s main gallery contains more than 2,500 items from old-time general stores, many in their original packaging: everything from Gillet’s Lye to Sweet Caporal “roll-your-owns” to Salada tea and hippo oil (not really from hippos!). There are biscuit tins and pocket watches, pablum and carriage bolts, horse liniment and clevis hooks, Red Rose flour and Prince Albert in the can.

One item of more than passing interest is Nonsuch Stove Polish, invented and marketed by the Golden brothers of Amaranth.

Everything is displayed just as it might have been in the old general stores, on counters, on shelves and in display cases, surrounded by the advertising claims of yesteryear.

The collection is the result of years of work by former antique dealers Bill and Shirley Little of Wellington County, and it paints a warm and happy picture of a time when the bond between customer and storekeeper was personal and treasured.

“What’s offered here is a rare opportunity to connect with a special part of our past in way that informs and entertains,” says museum curator Wayne Townsend. “We’ve tried very hard to make it realistic and I think we’ve succeeded. You can even hear the little bell ring when you walk in the door. About the only thing we couldn’t do was make the screen door catch you in the butt, just like it did in the old days!”

Dufferin County Museum and Archives is located on the northeast corner of Hwy. 89 and Airport Road. The building alone is worth a visit.

For more information, visit www.dufferinmuseum.com, or call 1-877-941-7781 or 705-435-1881.

Related Stories

Keeping the General Store Alive in Headwaters

Jun 20, 2019 | | CommunityLocal shop owners lean on lattes and eggs Benedict, artisanal gifts and festive community events – even Airbnb suites – as they serve their communities.

I have a water colour of the Mono Centre General Store the sign on the front reads E Tate Proprietor and is signed by what looks like LJ Brown. Does any one know anything about this? Holly Knowlton

Holly Knowlton from Alliston Ont on May 5, 2013 at 8:07 pm |