Baseball Memories

When baseball fever swept North America in the late nineteenth century, the good people of these hills signed on, but they embraced the game with a unique, local flair.

If a time machine could take baseball fans back to some of the wonderfully unusual games of the past, a good place to start would be in Orangeville on July 1, 1888.

As part of the Dominion Day attractions, a match had been arranged between a team of senior boys from Orangeville High School and a club from Hillsburgh. After piling up a lead of 14 to 4 by the fifth inning, the hometown boys were suddenly faced with the bases loaded as Hillburgh’s power hitter took the plate. True to baseball’s mystical drama, he let go a towering fly to right field. It came down fair, hit a rock, bounced into the crowd, and landed in a baby carriage. Players on both teams were just as surprised as the baby. Hillsburgh scored four runs on the play and the tide turned. In the next inning Orangeville’s excellent catcher was taken out with a broken thumb and Hillsburgh pulled into a nail-biting lead of 27-26 with just one inning left to play. At this crucial juncture, Umpire Bert Rowcliff, from allegedly neutral Alton, inexplicably declared the game over and Hillsburgh the winner.

The popularity grows

The hometown crowd was furious, and Rowcliffe’s peculiar decision that day no doubt contributed to the intense baseball rivalry that soon developed between Orangeville and Alton. But that July game was noteworthy for another reason. Elaborate Dominion Day celebrations had become a solid tradition in Orangeville by the 1880s, attracting crowds from miles around to enjoy parades, fireworks, and an afternoon of sports, including lacrosse, football, horse racing and track and field. The Orangeville-Hillsburgh game was the first time baseball had been included. Not only that, but newspaper coverage of the game far outweighed all the other sports.

In fact, media coverage of Orangeville’s Dominion Day celebrations throughout the 1880s offers an interesting gauge of baseball’s rise in popularity. The celebrations of 1886, for example, included tug-of-war teams from all over the hills (Caledon, Garafraxa and Mono Mills were the winners that day). Track and field events attracted competitors from as far afield as Monticello, Erin and Cheltenham. The highlight, a lacrosse game as always, had the Dufferins taking on the Onondaga Indians of Brantford (although it was upstaged that afternoon by a short but mighty fireworks display that occurred when a glowing cinder from one of the food concessions landed on a wagon loaded with the evening’s explosives!). But there was no baseball that year or the next. By 1889, however, the year following Hillsburgh’s controversial victory, the Dominion Day festivities included three baseball games with teams from Erin and Hillsburgh meeting local teams in competition for a silver cup.

Even so, Orangeville continued to be primarily a “lacrosse town” well into the next century. In other communities, though, baseball grew rapidly. Ballycroy and Mono Mills embraced the game. Alton started playing in 1875 and eventually grew into a powerhouse. Churchville and Erin were underway early too, perhaps because of their proximity to Brampton, where a team had formed in 1871. By the end of the century, there were teams in almost every community. In places such as Terra Cotta, Inglewood and Waldemar, these tended to be pickup teams, responding to one-off challenges from neighbouring villages. However, some communities, such as Bolton and Alton, developed high-flying signature teams.

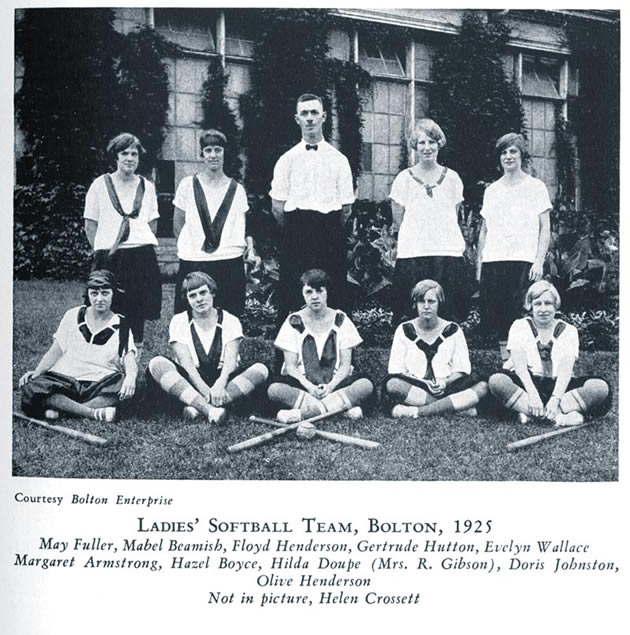

BOLTON LADIES SOFTBALL TEAM, 1925 ~ Softball originated in 1887 at the Farragut Boat Club in Chicago, invented as baseball to be played indoors. Originally dubbed ‘kittenball’ (and other names like ‘mushball’ and ‘cabbageball’) the game evolved rapidly into an outdoor game. By the turn of the century, it had become extremely popular among women players whose skills were anything but ‘kittenish.’ In 1925, the Bolton Ladies Softball Team won the All-Ontario title and advanced that year to the semi-finals of the Canadian Championship played at the CNE. Courtesy The Region Of Peel Archives PN2011 _ 0 0668

Nothing better than a winning team

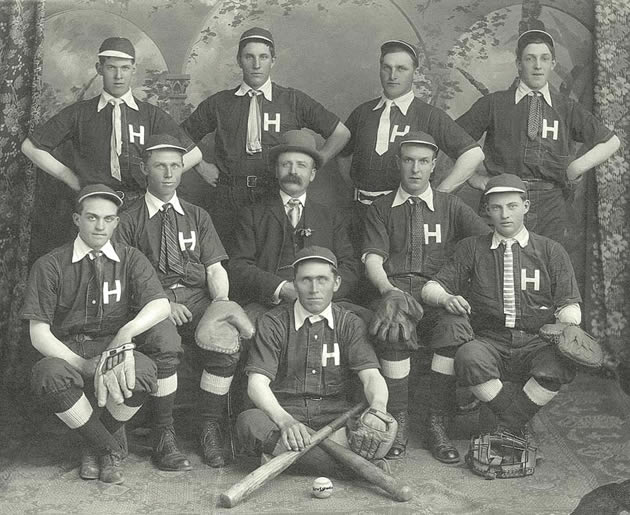

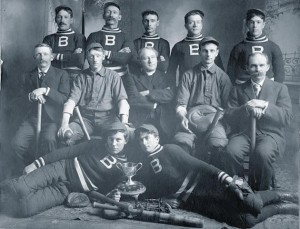

Bolton: The Hottest Team In The Hills back row : Daniell Henderson, Harry Sheardown, William Robertson, George A. Norton, William Swinerton, Joseph Robertson. middle row : Asley Norton, Stewart Cameron, Rev. Martin. front row : Reuben Sheardown; Albert Pilson. Courtesy The Region Of Peel Archives PN20 08 _ 0 0 093

Nothing drives the popularity of a sport like having a winner in the community, and early on Bolton had that a big way. In 1885, Bolton’s red hot nine (starring local pitching hero Harry Sheardown) not only defeated every other team in Peel, including mighty Brampton, it went on an Ontario tour, winning by scores such as 24-4 over Aurora and 30-12 over Cobourg. It even attracted national attention by trouncing the Toronto Athletics 18-1.

With a role model like that to emulate, it’s no surprise that junior squads formed quickly. One of the more successful was the Bolton Young Athletics Baseball Club. Their most successful year was 1889 when they played well enough to challenge the notorious – and undefeated – Woodbridge Maple Leafs, famous for the “curve pitcher” on their roster.

Bolton’s youngsters were leading by a healthy 18 to 8 in the fifth inning of the match with the Maple Leafs and might have scored an historical win. But then, at the top of the sixth, the sound of a train whistle came wafting in from the distance and the entire Bolton team abandoned the field and raced for the station. It was the last train of the day and their only ride home.

Support for “Our Boys”

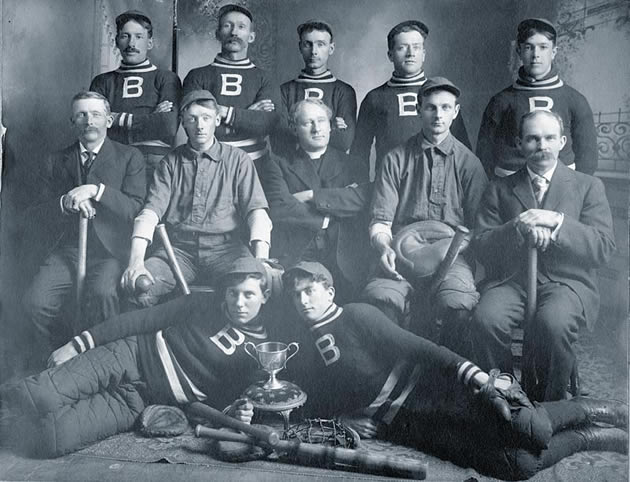

Although Bolton’s senior team disbanded in 1890 it didn’t take long for another banner carrier to emerge in the hills. In 1893, the Alton Aetnas had begun to attract attention and within a few years the team from this tiny village was being invited to play against London, Hamilton and Toronto.

In addition to their stellar play, the Aetnas had an extra player on the bench so to speak. According to the Perkins Bull histories, no team anywhere in Canada enjoyed the intense support the village of Alton gave its “boys.” Beginning with the very first game in 1875, in the words of Perkins Bull, “Farmers of the surrounding district forsook their ploughs, mechanics in the village laid down their tools, as Alton men and women alike donned their Sunday best and went out to cheer their Aetnas at home or abroad.”

For those who think Bull’s prose ran to hyperbole, consider the part played by village supporters in a special game during the 1898 season. By this time, baseball rivalry between Alton and Orangeville was thoroughly, even bitterly, entrenched. The Aetnas were still the hot team in the hills, but that year Orangeville had fielded an unusually able nine and, after losing a close game on Alton’s turf, insisted that biased umpiring was the cause.

Challenge and counter-challenge filled the air (accompanied by occasional fisticuffs in the taverns of both communities) until Orangeville proposed a special exhibition game on neutral ground in Erin for a wager of $100. Alton’s money for this grand encounter was secured by public subscription, with 10¢ and 50¢ contributions collected door to door. The entire village travelled to Erin for that special game only to watch Orangeville win in a cliffhanger and see the bet duly paid. That disappointment produced no wane in support in Alton though. The entire village lined the field for the very next Aetnas game.

Whatever it takes to win

The village of Palgrave also developed into a baseball hotbed. Although there are several high points in the village’s baseball history, none generated greater satisfaction for the hitherto perennial losers than their defeat of Bolton (11-10) in 1895.

The habit of losing had begun early for the Palgrave team. In what is believed to be the community’s first-ever game against a team from another town (Tottenham, c.1881), it had lost by over 50 runs. The loss was understandable, because except for local sawmill operator, William Campbell, who had accepted the challenge from Tottenham, no one on the Palgrave team knew how to play! They lost their second game a few months later, this time to Lockton, but the final score was a little more balanced: 60 to 40. It seems the boys from Lockton didn’t know how to play either.

But on Dominion Day, 1885, the underdog triumphed over Bolton and the game marked a turning point for Palgave. For the next several years, they became a team to beat. Once they’d tasted victory, the Palgrave nine sought to avenge an ignominious defeat at the hands of Tottenham from years before and accomplished that in 1890. The final score, with the entire village present to cheer and bear witness, was a narrow 4-2, an indication that some pretty sharp baseball was played that day.

Still, the victory was not entirely without a touch of hanky-panky. While both teams boasted “curve pitchers,” increasingly common by then, Palgrave stretched the game’s implicit code: that a team’s players must be hometown boys exclusively. On the mound for Palgrave that day was Paddy Horan’s “hired man,” who was actually the star pitcher for the title-winning Toronto Crescents.

Not only that, but on the reasonable assumption that the Tottenham boys had brought in a ringer or two of their own, Palgrave packed a little extra insurance in their equipment bag: a loaded bat. This secret weapon not only provided the winning edge in the Tottenham game, but for the entire 1890 season and it bestowed such a reputation for the “long ball” on the Palgrave team that, inevitably, suspicions were aroused.

The truth came out at a game in Alliston during a bench-clearing brawl in which the Palgrave nine tried to hide the bat and Alliston’s team fought to expose it. When Alliston’s constable lined up both teams for a scolding before the game could begin again, there were only eight Palgrave players. The ninth man – and the bat – had disappeared through a hole in the fence. The bat was never seen again.

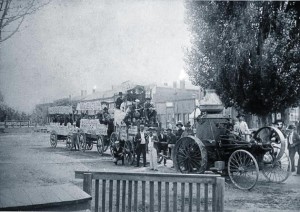

SAM BOGGS’ EXCURSION TO ERIN

Carriage maker, Sam Boggs, hooked three wagons behind his steam engine (used for powering threshing machines) loaded them with citizens of Alton and early on the 24th of May, 1897, set out for Erin at 4 km an hour for the afternoon baseball game. As Erin came into view, Sam announced their approach with a blast on his engine’s whistle, causing the engineer of an approaching CPR freight train to panic in fear there was another train on his track. The trainman brought his charge to a screeching halt and while it stood stalled in its tracks, Sam crossed in front, tooting a thank-you salute as he did so. That afternoon Alton won the game.

Good will and good fun

Although various forms of mischief, like loaded bats or the notorious spitball, have always been a part of baseball, they didn’t really play much of a role with our local teams. Not that advantage wasn’t taken whenever possible. Shelburne, for example, is alleged to have maintained several bumps and holes under the too-long grass of its outfield. The local nine had the locations well mapped out in their heads, but the visiting team invariably learned the topography the hard way.

Such schemes worked fairly well for small communities in the early days of baseball, before they were organized into sophisticated and regulated leagues with a season of scheduled games. But that step was didn’t arrive until the coming of the automobile. Until then, travelling from town to town to play was challenging and time-consuming. And in rural areas, harvest cycles had priority. On August 9, 1901, for example, when the Palgrave Maple Leafs failed to show up for a game in Bolton, nary an eyebrow was raised, for the summer had been a wet one and when the sun finally shone in earnest that month, threshing machines in Albion Township were humming.

Thus, in baseball’s early days, most games were either home-and-home challenge matches between two communities, usually coinciding with Dominion Day or the Glorious Twelfth, or a challenge match within a single community.

Typical of the latter was a game played in Bolton on Labour Day, 1901. The young men of the town, The Bachelors, defeated a team of older men, The Benedicts, by three runs. So entertained were the many local spectators that a rematch was scheduled. The Benedicts lost again, once more to the great amusement of the spectators who were no doubt aware that the team of older players was missing a key man. Earlier in the summer, Tom Robinson, one of those hitters who could make outfielders back up to the fence simply by stepping up to the plate, had accepted a challenge from companions who wagered he could knock out a cow with his fist. The cow stood her ground, the bettors lost their money, and Tom broke his hand and landed on the injured list.

The Bachelor-Benedict game was hotly contested but played in good-natured fun. Even a gross error by the umpire was forgiven because, as the Bolton Enterprise reported, “it was getting quite dark at the time and third base was an imaginary spot where grass did not grow.”

Reaction to an umpire’s behaviour was not always so sanguine, especially when a decision seemed unusually arbitrary. One such case was Umpire Rowcliffe’s sudden declaration in Orangeville in the 1888 game with Hillsburgh. (Rowcliffe, according to reports, was noticeably absent for the rest of the day’s activities.)

Another case, which caused a free-for-all that drew attention beyond these hills, developed at a game in Alton in 1901. After Hillsburgh’s visiting nine had been on the receiving end of several dubious calls, a Hillsburgh batter approached the plate while eating an orange. What passed between him and the umpire is unknown, but before the unbelieving eyes of all present the batter suddenly threw his orange at the umpire – who responded by decking the batter with a punch to the jaw! In the words of Perkins Bull, “a donnybrook ensued.”

It was a major dustup. Not only did the players from both teams end up in a mass wrestling bout, but so many fans joined the fray that there was no one left to bring peace. It was not until the imbroglio simply ran out of steam that order prevailed. Curiously (or perhaps not), the umpire disappeared during the melee. He was later said to have hidden out at the train station until he could grab the first available transport out of town.

Perhaps more intriguing, is what developed once the dust had settled. There was no more baseball that day. It was getting late. And crucially, there was another event on tap: a dance. Not just any dance, either. Dick’s Foundry had been renovated after a serious fire to serve as a community centre and the dance there would boast an imported orchestra and specially catered refreshments. Whether this temptation alone dispelled the antagonism or whether it did so in concert with the good will that naturally connected the two communities, the end result was that the teams shook hands, the fans cheered, all was forgiven and everyone went to the dance.

Later that evening, it was agreed that because Hillsburgh had been leading when the interruption occurred, then Hillsburgh had won the game. After all, there would be more games to come between the two villages and plenty of opportunity to work out whose team was superior. In the meantime, neighbours are neighbours and it’s best to get along. That’s how baseball was played in the hills.