Free Range Pig

I was hoeing the garden when Dillinger suddenly came around the henhouse, trotting along like he was on his way to the bank. He was sunburned and covered with dirt.

True confessions from the ninth concession

Every year, I load an old wooden crate on the back of the truck and drive off to find two young pigs to raise up for the freezer. They go into a pen in the barn for a few weeks until they settle down, and then I let them out in the orchard to fatten over the summer. It’s great meat, dark and flavourful, and reminds people of what pork used to taste like in the days when pigs lived outside.

The drive gets a little longer every year. The only man I know who still keeps a boar and a few sows lives ten miles away, up over the hill in the wilds of Grey County. This year, I decided to bring home an extra one for my neighbour Hughie, who gave up the last sow herd in this community several years ago. He still misses his pigs and I thought he needed one to come and visit.

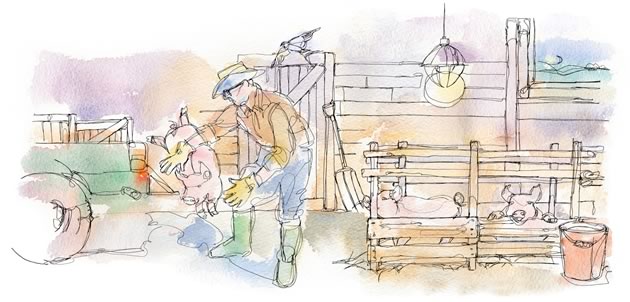

When I got home, I backed into the barn, opened the door of the crate, grabbed the first pig by the hind legs and carried him, kicking and screaming, into the pen. Pigs are a lot like teenagers. If something doesn’t suit them, they fight and kick and yell their heads off. The second pig went the same way.

The third one looked at me and made one of those instant mental calculations for which pigs are famous. “Wheezy guy with glasses,” he said to himself. Then he ducked under my arm, shot off the tailgate, squeezed out under a door, and disappeared into the dark.

Don’t worry, he said, the way the times are, even a pig knows you don’t walk away from a place where they’re feeding you. Illustration by Shelagh Armstrong.

I slept fitfully that night. The last time this happened to me, I was nine years old. My first two pigs got away through a hole in the pen one night and ran for five miles before they were captured. Pigs can live in the wild indefinitely. They’ve been domesticated for 10,000 years, but given the chance, they go feral in about an hour and a half. (Which is another parallel with teenagers, I suppose.) This fugitive had more than a mile of stream and thick bush to hide in and a 20-acre wheat field to munch on.

“He’ll be fine,” said my wife. “He’ll get lonesome for the others and come back.”

“Maybe,” I said. “What about coyotes? What if he goes down to the highway?”

The first sighting came the next afternoon, down the road on a neighbour’s lawn. But he ducked into the wheat field and headed northwest at a dead run. Hughie’s son hopped on his four-wheeler and buzzed around the field to cut him off. But he didn’t come out. By morning, the pig was on Facebook and had a name: Dillinger.

Hughie came over the next morning. “Don’t worry,” he said. “The way the times are, even a pig knows you don’t walk away from a place where they’re feeding you. Besides, your pig is performing a valuable service. It used to be that you never saw your neighbours all summer unless a pig got out. They do a great job of keeping people in touch.”

“You’re taking this very well,” I said. “He was actually your pig.”

The pig went off radar for three days and I began to fear the worst. Then I went out to do the chores one evening and stopped short. There was Dillinger, standing in the barn doorway with his head in a tub of feed. I shooed him into the barn, but he flashed the grin of a pig who knows he’s at the top of his game, squeezed through a hole in the wall and vanished again.

A few days after that, I was hoeing the garden when Dillinger suddenly came around the henhouse, trotting along like he was on his way to the bank. He was sunburned and covered with dirt. When he heard a “noof” from the pigpen, he paused and sniffed the barn wall. Then he sighed. On a hunch, I walked right past him into the barn and opened the pen door. He hesitated for a moment, looking from the woods to the barn. Then he shrugged, trotted into the pen and flopped down beside his brothers.

Dillinger has shown no interest in going over the wire since then. Some would say he made the fatal mistake of trading a little freedom for a little security. But I don’t think he sees it that way. True liberty is the freedom to choose. And Dillinger has opted for three squares a day and freedom of mind.