The Bob Edgar Telephone Company

Beginning in the late 1920s, though, a series of government regulations along with profit-driven business decisions gradually changed telephone service across the country into a fluid network.

In the early days of the telephone, the Bell Telephone Company was busy installing service in urban centres and stringing long distance lines between them. Sideroads and concessions had very low priority.

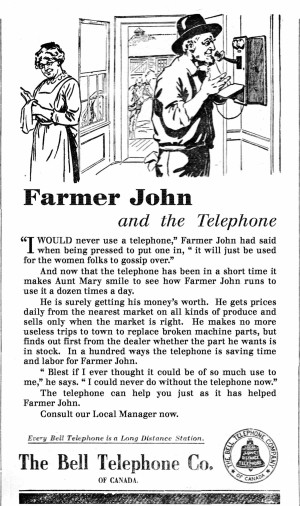

By 1915 the demand for telephones in urban centres had mostly been met, so the Bell Telephone Company turned its attention to the countryside.

The Bell Telephone Company established a telephone exchange in Orangeville in the spring of 1887. Very shortly thereafter, 69 subscribers enjoyed telephone service from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. on weekdays, and 2 to 4 p.m. on Sundays. That same year the exchange was linked to Alton, 9 kilometres away. By 1891 it was linked to Shelburne, 25 kilometres north, and to Bolton, 35 kilometres south. So, in 1900, it was reasonable for the good citizens of Amaranth Township to assume they would be successful in their push to have Bell link west to Bowling Green, just 19 kilometres away.

However, it is also reasonable to assume that deep in the bowels of Bell headquarters the decisionmakers had never heard of Bowling Green, and certainly not of Farmington and Biggles, both of which could have been included on the line. Not that knowing the geography would have made any difference. The bottom line – and that’s what it was ultimately about – was that Bell considered Amaranth simply too rural for the company to service profitably. It was just not on. So Robert Henry Edgar stepped up.

Bringing in the Sheaves

Bob Edgar had been a teacher in East Luther. He was also a lay preacher much sought after throughout Dufferin for his marvellous singing voice. Above all, he was a self-starter with mechanical aptitude, and in 1906 he singlehandedly built a rural telephone system. Its first line, with 300 subscribers who paid $2 a year, stretched from East Luther through Bowling Green to Laurel, with the wire strung along treetops, fence posts and even the occasional pole. Switching equipment was located in private homes and farmers’ wives became the operators.

Bob did all the installation himself (while singing hymns at the top of his voice), and all the billing and collecting (he signed receipts “Yours in Jesus’ Precious Name”). He did all the servicing too, patrolling the lines with a horse named “Old Bill” that local wags claimed knew the route better than Bob. An unsophisticated system to be sure, but the fact that it eventually spread to parts of East Garafraxa, Mono and Mulmur indicates it was a service much in demand.

Bob Was Not Alone

While Robert Edgar might well be considered unique, establishing a private independent telephone company in the early years of the 20th century was not. In 1910, when Bob’s system was just four years old, there were 459 other companies operating in Ontario. The Telephone Act that year made the Ontario Railway and Municipal Board responsible for regulating these systems and was, in part, designed to discourage their spread, but they continued to grow, ultimately peaking at 689 in 1921.

The cause of this proliferation lay in the dynamic early history of the telephone. Alexander Graham Bell’s invention was only 11 years old when Orangeville’s exchange opened in 1887. Even earlier, in 1878, was the telephone exchange in Hamilton, the first such in the British Empire (second in the world), with wooden telephones so heavy they had to be held with two hands. By the 1890s the demand for telephones was universal and intense. No community wanted to be left behind.

In December 1888, for example, Shelburne’s council, which had dithered over the cost of installing 400 poles for the town’s local exchange, panicked at the news that tiny nearby Primrose had got telephone service, and jumped through hoops to get the town’s system up and running just months later.

This was a familiar instrument in many farm kitchens. Turning the crank – once – connected the caller with an operator (usually known as “Central”) who was told the intended receiver’s number (or often just his or her name). The operator would then make the connection. To connect with a subscriber on the caller’s own party line, a caller did not need the operator, but could “crank” the intended receiver’s number. On a party line, each subscriber was given a specific ring variation (for example, one long ring and two short) and, in theory at least, would pick up only when that variation rang.

Although blaming Bell Telephone for failure to provide rural service soon became a popular sport, the situation was not entirely the company’s fault. In 1880 the federal government had granted Bell a charter giving it a virtual country-wide monopoly. Because the telephone was such an instant hot item, the company’s entire resources were devoted to stringing long distance lines to connect the services they were building rapidly in urban centres.

The Bell charter was revoked only five years later, but by this time demand for service had grown even further beyond Bell’s capacity, with the result that independent telephone exchanges mushroomed across the province.

Rationalizing the Network

With so many telephone companies – owner-operator, shareholder owned, municipal nonprofit, etc. – it’s no surprise the quality of service varied immensely. This was especially true of interservice connection. Consider the challenge to a telephone customer on Bob Edgar’s line in Grand Valley. That customer could call fellow users on the line, but to call someone in, say, Erin was a problem. Most lines that connected different communities around Ontario belonged to Bell and unless the local independent system was tied in – for a fee – long distance calls to another community were out of the question.

In 1903, for example, before Bob’s system was built, Bell had run a long distance line to Laurel Station and installed a single telephone. But the Edgar line didn’t tie into it until 1918. (Not necessarily Bob’s choice. In the early days, even for a fee, Bell was notoriously reluctant to allow independent systems to connect with its own.)

Beginning in the late 1920s, though, a series of government regulations along with profit-driven business decisions gradually changed telephone service across the country into a fluid network. By 1975 in Ontario, only 24 independents remained. Many smaller ones had combined resources but even more were taken over by Bell. Bob’s system, for example, which had become incorporated as The Edgar Telephone Company in 1918, morphed into several different entities in succeeding years, all of them taken over by Bell in 1954.

Robert Henry Edgar died in 1938, having made a significant contribution to his neighbours and to these hills, but the question remains: Was Bell Telephone right in 1906? Did providing telephone service in Amaranth make no financial sense?

According to Amaranth historian, Elizabeth Kelling, by the mid-1920s Bob had become wealthy enough to acquire most of the village of Bowling Green. On the other hand, at the time of his death, he still owed Phyllis Maltby, the operator at Laurel, a full six years of back pay. So, was it a viable business? Who knows?

More Info

The Party Line

Technology and economics made the much bemoaned “party line” the default system in rural areas. The standard complaints about it, of course, were lack of privacy and availability of the line to make and receive calls. There was even the real risk that a line with up to 20 or more subscribers would be completely drained of power if everyone chose to “listen in.” On the other hand, there was the time Bill Fish of Mono learned that two handicapped seniors in Whittington were running out of wood during an especially cold winter, so he organized an emergency wood-cutting bee simply by picking up the phone on his party line.

The Telephone was Invented in Canada (Sort of)

Alexander Graham Bell’s patent was attacked by over 600 lawsuits in the years following its filing on February 14, 1876, with the majority arguing that his invention-cum-patent was not first, and therefore not valid. Bell’s consistently successful defence against the barrage of litigation was based primarily on notes and diagrams he had made in the summer of 1874 at the family home near Brantford. His technical theorizing was also recorded in the daily entries of a diary kept by Professor Melville Bell, his father. Bell, the younger, is reported to have insisted that the theory, made fact in Boston, was first developed in Canada.

Related Stories

The Need for Speed

Jun 17, 2014 | | CommunityWe’ve been hearing about rural broadband for more than a decade. So where is it?