River World

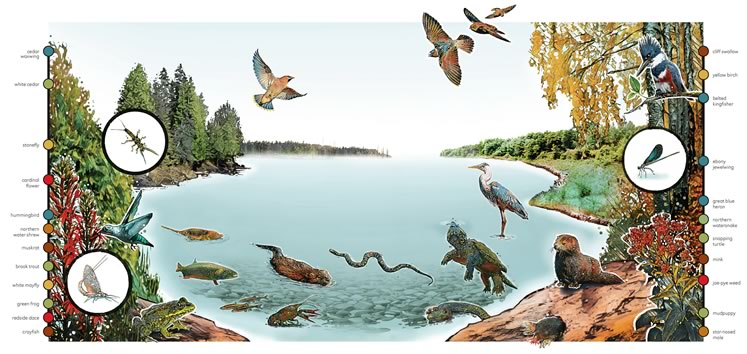

The Credit, the Humber, the Grand and the Nottawasaga rivers are home to a lively community of creatures that form a complex, interdependent web of life.

The Credit, the Humber, the Grand, the Nottawasaga – the four rivers that have their source in our hills – are home to a lively community of creatures that forms a complex, interdependent web of life. Here’s an introduction to some of them.

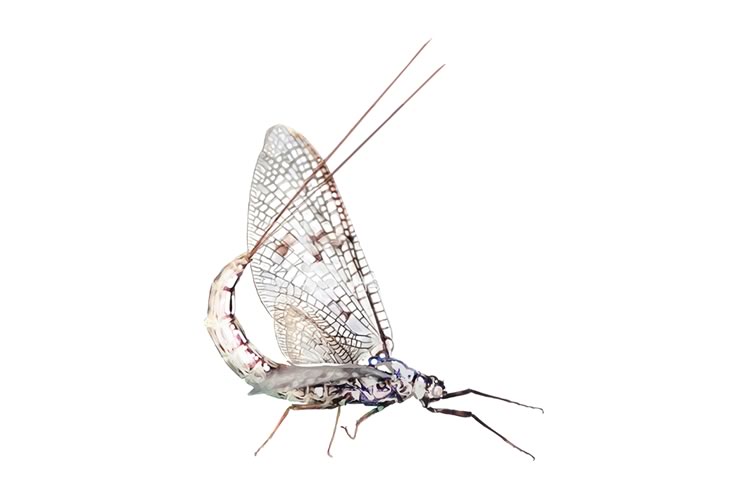

Skytree Smith is a shadfly soothsayer. Skytree – yes, she’s a child of the ’60s – has the uncanny ability to predict the exact day of the mass emergence of shadflies, aka mayflies, on the Credit River in August. And why does she bother? To witness an extraordinary event that lasts but one hour of the 8,760 hours in a year. Millions upon millions of mayfly larvae wriggle to the surface of the river and transform into ghostly white flies with gossamer wings and filamentous double tails.

“They fill the air above the river like a living blizzard,” says Skytree. “It’s mesmerizing.” Their tasks during that hour-long window are simple but urgent: mate, fly upstream, lay eggs.

For a decade, Skytree has invited friends to witness this spectacle on a bridge in the hamlet of Glen Williams, where she lives and produces works of art at Glen Williams Glass. She enjoys teaching children about the mayflies and watching the bolder kids stand within the swirling torrent of insects, laughing and shrieking.

To foretell the hour of the mayflies, Skytree watches for subtle cues. She pays attention to the mayflies downstream in Norval because they tend to appear a little earlier. She checks spiderwebs along the river for mayflies that emerge early. “The shadfly emergence is like a bell curve,” she explains. Most emerge at dusk on a single evening, but some mayflies are outliers, appearing before or after the main event. Other cues verge on the mystical. Skytree swears, for example, she can smell the approaching emergence of the mayflies: “The odour rising from the river is fishier than usual.”

You’d be forgiven for wondering why Skytree is sweet on mayflies. She finds them lovely, but she also recognizes their ecological value. “So many other species rely on them,” she says.

She’s right, of course. Any insects as prolific as these mayflies are bound to feed a host of other animals including fish, birds and bats. Flyfishers know this. “Match the hatch” has long been a mantra of the fly-fishing community. They know that wary trout can be fooled by artificial flies crafted to mimic the pattern and colour of emerging mayflies and other river insects such as stoneflies and caddisflies.

Skytree’s shadflies are a species commonly referred to as white flies because of their pale coloration. They remain abundant in many streams in southern Ontario. Another mayfly species called the green drake has not fared as well. According to Henry Frania, an entomologist with the Royal Ontario Museum, this lovely mayfly is “regarded as sensitive to pollution of various sorts.” It appears to have disappeared from the Humber River and has been reduced to a few locations in the watersheds of the upper Grand and Nottawasaga. Along the main branch of the Credit River between Cataract and Forks of the Credit some resurgence has been documented since 2007, but the insect scientist says they have not recovered at all on the west branch.

This matters. When I speak to Bob Morris, chief watershed specialist with Credit Valley Conservation, he reminds me that mayfly, stonefly and caddisfly larvae have long been recognized as indicators of water quality. The decline of the green drake mayfly tells us that although the health of our rivers has improved in recent decades, problems persist. Rivers are intimately connected to our towns, roads and farms through groundwater and runoff often contaminated with salts, pesticides and other pollutants.

Bob has kayaked the length of the Credit River from Island Lake (lots of portaging in the upper sections!) to Lake Ontario. He knows that water quality is one determinant of the diversity of river life. He also knows that diversity is enhanced by the ecological niches rivers create. Fast currents scoop soil under stream banks, creating hollows where trout shelter. Where currents slow down, sand and gravel are deposited, creating shallows where stream-dwelling shorebirds called spotted sandpipers forage for insects and crustaceans. Green frogs sit like amphibious Buddhas in these quiet waters, waiting for flying insects such as ebony jewelwings to flit within range.

Rivers also create floodplain habitat when water levels rise after snowmelt in late winter. When the water returns to its regular channels, it leaves behind rich organic matter that nourishes plants and, in turn, animals. Snapping turtles overwinter in the soft, saturated soils of these floodplains. From valley floor to valley crest, the differences in soil, moisture and shelter offered in the basins carved by rivers provide ecological niches suited to particular plants and animals.

Bob cites the vital importance of our rivers as corridors that channel the movement of myriad forms of wildlife. The streams of Headwaters “connect the Great Lakes to the interior,” he says.

Fish are obvious travellers on these aqueous highways, but mammals and birds also depend on rivers to guide them. Consider a cliff swallow, tired and hungry after flying across Lake Ontario, arriving in Etobicoke in May. The vast city extends before it. The swallow knows the buildings, roads and manicured lawns can’t sustain her. But she sees a ribbon of trees snaking northward from the lake toward distant hills. Her choice is clear. She’ll join other swallows and thousands of fellow migrants on a journey up the Humber River. During that journey, she’ll feed on flying insects over the water. To power their northward flight, other migrants, including more than 20 species of diverse and colourful warblers, will hunt insects and caterpillars on the greening shrubs and trees of the valley.

Our swallow travels upstream through Etobicoke, through Bolton, to the bridge in Caledon where her parents built the earthen nest she was reared in two years earlier. Some of the warblers will stay to nest along the Humber as well. Others may use river valleys such as the Humber and Credit to guide them to nesting territories on the Niagara Escarpment and the Oak Ridges Moraine. The Grand River in the western Headwaters region undoubtedly guides migrating birds too, providing a safe, food-rich conduit through agricultural southwestern Ontario to good nesting habitat upstream. Waterfowl – ducks, herons, egrets – travel the Grand to access the vast wetlands of Luther Marsh.

At least 52 species of fish have been found in the Nottawasaga River and its tributaries. The counts for the Humber and the Credit are about 75 and 79 respectively. The Grand River, by virtue of its size, and the fact it is connected to the warm, fertile waters of Lake Erie, harbours more than 90 species. Though fewer species inhabit the upper reaches of these streams, the cool, well-oxygenated water supports fish that can’t survive in the warmer, silt-laden waters farther downstream. One of these is the beautiful and endangered redside dace, a minnow with a spotty distribution in southwestern Ontario, which includes small sections of all four of the main Headwaters watersheds.

In the 1970s I pickled several redside dace for a field biology course I was taking at the University of Toronto. The memory makes me cringe, though they had not yet been designated a species at risk. I found them in a limpid pool of a small creek just before its confluence with the Credit River. As the swimming dace caught the sun, they glinted like aquatic fireflies. I recall the words of my professor when he saw them: “Looks like you painted them with Mercurochrome!”

Water clarity is essential for these minnows. They look for low-flying insects and then leap to capture them.

Much better known than redside dace are the brook trout that still thrive in many Headwaters streams. The upwelling of cool, clean groundwater, filtered by the sand, gravel and stone of the Oak Ridges Moraine and the Niagara Escarpment, is important to the survival of this species. So is the cooling shade cast by streamside trees such as white cedar and yellow birch. Trout also need plenty of oxygen, and the rapids and riffles of Headwaters streams ensure a good supply. Skytree’s shadflies feed both larval and adult trout. Other bottom-dwelling insects and crustaceans, collectively called benthic invertebrates, also feed trout, as do small fish.

Sue Hopkins VanZant lived along the Nottawasaga River in Hockley Valley for 11 years. Some Septembers the river held enough water to grant passage to migrating steelhead, aka rainbow trout, past her family’s property. On quiet nights they could hear these impressive fish wriggling and splashing as they worked their way upstream. Steelhead, originally introduced from the Pacific Northwest, grow big in Georgian Bay and then travel inland to spawn in the upper reaches of the Nottawasaga and its feeder streams.

The Credit and Humber rivers also boast autumn runs of introduced trout and salmon. (Steelhead run in the Grand River as well, but not as far upstream as Headwaters.) These spawning runs offer hints of the former glory of the Atlantic salmon runs in Lake Ontario’s feeder streams. There was a staggering abundance of Atlantic salmon in these streams before dams, land clearing and profligate slaughter – think American bison and passenger pigeons – finished them in the late 19th century.

One example of frenzied harvesting was highlighted by K. M. Lizars in his 1913 book The Valley of the Humber, 1615-1913: “The men speared as fast as they could throw the fish behind them. In drawing up their boat they had inadvertently left it halfway across a log, and, too busy to take their eyes off the water, they worked until a crash made them look behind them. The weight of the fish had broken the boat’s back; and that was not by any means a record take.”

Atlantic salmon are being reintroduced to some Lake Ontario streams, but the massive spawning runs of the 19th century will likely never be seen again.

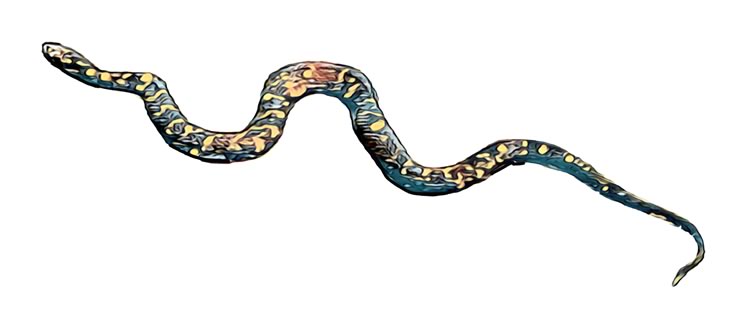

Of course, where fish dwell, so do predators bent on having those fish for dinner. Several species of birds can be found hunting fish along Headwaters streams, including herons, kingfishers, osprey and mergansers, ducks with serrated bills to catch and hold their slippery prey. Great blue herons exercise great patience as they walk slowly along streambeds, their eyes fixed on the water below. When the herons spot movement, they lean forward with the deliberateness of a tai chi master before flashing their stiletto beaks into the water. Fish are often the catch. But herons aren’t choosy. Frogs, watersnakes, small turtles, large insects and even young muskrats are all fair game.

The kingfisher is another fish-eating bird that is hard to miss. Built like a blue jay on steroids, this impressive bird seems to exude self-assurance. With a loud rattling call, kingfishers are usually heard before they are seen. I bet a tracking device attached to a kingfisher could be used to map the twists and turns of streams, so closely do these birds orient their flight to these watery paths.

Mammals also get into the fish-eating act. Otters live along the Nottawasaga. These large, aquatic weasels are superbly adapted to hunt fish. Farther south, on the Grand, the Credit and the Humber, otters are less common, but there is an abundance of mink, another fish-eating member of the weasel family. Bob Morris watched one hunting along the Credit River. It dove beneath an undercut bank and a brook trout shot out, thrashing up a gravelly riffle on its belly, with the mink in hot pursuit. “It was an amazing sight,” he says.

Living by a river is wonderful, but it requires a certain level of forbearance – an acceptance that we are but one of many species drawn to it. Houses and yards become habitat features for the local wildlife. For the Hopkins VanZants, this meant deer in the garden, bats in the attic and snakes in the basement. Sue and her husband patched cracks in the stone foundation, but the house never became completely serpent proof – small milk snakes still found their way in.

Another friend, whom I’ll call Paula, also discovered that when you live near a stream, wildlife will come calling. Paula once killed a star-nosed mole that had found its way into her basement, likely from nearby Caledon Creek. Paula is one of the kindest persons I know, so this act of mole-icide was very much out of character. For her, the mole, with its oversized shovel-like forepaws and bizarre nose sprouting fleshy appendages recalling Medusa’s hair, was simply too much to bear. (That the mole was the size of a hamster didn’t temper her horror.)

Though star-nosed moles are common stream creatures, their subterranean lifestyle means they are seldom seen. The nose that frightened Paula serves as an intriguing tactile sensory system. Though these creatures are nearly blind, the incredibly finely tuned sense of touch provided by the fleshy “fingers” on their snouts enables them to form a high-resolution representation of their environment. Star-nosed moles are also said to be the only mammals known to smell underwater, though it surprises me this ability hasn’t been noted in whales. Apparently, the moles blow air bubbles and inhale them to sniff for invertebrate prey such as mayfly larvae.

Star-nosed moles illustrate the fantastic life forms that live along our rivers but are little known. Another is the northern water shrew, a diminutive mammal with amphibious inclinations. Though these shrews are comfortable on land, they can swim down to the stream bottom to seek crustaceans and insect larvae. And astonishingly, if subsurface exploration doesn’t appeal, they can also walk on water. Well, run, actually – in the manner of tropical basilisk lizards. This is possible because, at only 10 grams or so, they are featherweights and equipped with hind feet that trap air and cushion their footfalls on the water’s surface.

The mudpuppy is one of the most enigmatic of life forms in our streams. A mudpuppy is essentially an amphibian that doesn’t grow up. Though many other salamanders have gills during their larval stages, mudpuppies never lose theirs. Few of these wholly aquatic salamanders have been found in Headwaters, but that doesn’t necessarily mean they are rare. Mudpuppies are inconspicuous despite their impressive 40-centimetre length. They hide under stones during the day and emerge after dark to hunt minnows and crayfish. In turn, northern watersnakes hunt them.

Predatory connections between river animals such as crayfish, mudpuppies and watersnakes abound. So do benign connections between river, plant and animal. Often these relationships are imbued with beauty at every turn. Picture a crystalline stream wending through a woodland of hemlock, basswood and maple. Dapper cedar waxwings pursue insects over the water. It’s late summer. Sunlight filters through the leaves to illuminate a patch of wildflowers growing streamside. Joe-Pye weed stands tall, offering nectar-rich blossoms to squadrons of bees and wasps.

Closer to the stream, cardinal flowers flicker intense red. These magnificent plants grow along streams not only because they need moist soil but also because they thrive in dynamic environments in which water levels fall and rise. Their basal rosettes are often completely submerged in spring but rest above water during the summer. Other plants probably can’t cope with these changing water levels, giving cardinal flowers a competitive advantage.

As streams are good for cardinal flowers, cardinal flowers are good for hummingbirds. The red colour of cardinal flowers beckons these tiny aerial acrobats. The flowers’ nectar supply is found at the bottom of a long tube, out of the reach of most pollinators but perfect for the long beak of a hummingbird. And astonishingly, the cardinal flower has a structure that arches outward to fit perfectly over a hummingbird’s head, dusting it with pollen as it probes for nectar. Stream, cardinal flower, hummingbird – a beautiful example of the essential interconnections of the natural world.

The life of Headwaters rivers is diverse and endlessly fascinating. A synergy exists between plants and animals and their riverine habitats – links that weave a complex ecological tapestry. Skytree Smith knows mayflies are an important part of that tapestry. She believes their numbers have dropped during the decade she has celebrated them in Glen Williams, and she wishes the local ballpark would cancel play during the insects’ brief annual emergence. The ballpark lights distract huge numbers from their vital reproductive business, and this rends the tapestry of life along the river.

Protecting our rivers can be as focused as turning off ballpark lights for two or three August evenings in a Credit Valley hamlet. Or it can be as expansive as the Greenbelt that surrounds Ontario’s populous Golden Horseshoe. Habitat will be protected “as long as the Greenbelt holds,” says Bob Morris.

Some might ask why we should care about mayflies, or redside dace, or star-nosed moles, or other riverine life. Here’s an answer from David Attenborough: “It seems to me that the natural world is the greatest source of excitement, the greatest source of beauty, the greatest source of intellectual interest. It is the greatest source of so much in life that makes life worth living.”

Illustrations by Anthony Jenkins.

Related Stories

The Flight of the Mayflies

Sep 14, 2019 | | Notes from the WildThe annual emergence of mayflies, wherever it occurs, brings predictable responses.

Benthic Invertebrates

Jul 3, 2019 | | Notes from the WildThe abundance of these aquatic larvae in our streams and rivers is a good thing.

The Grand River – When Your Neighbour is a River

Jun 20, 2016 | | Historic HillsNot only does the Grand River lay out nature’s beauty, it also offers opportunities for recreation, commerce and development. Yet all this comes at a cost, for the Grand can be both friend and foe.

Hurricane Hazel’s Place in Headwaters’ History

Sep 18, 2018 | | Historic HillsWhen Hurricane Hazel finally blew itself out in October 1954, the damage and casualties left behind made it Ontario’s biggest weather event of the century. The flood control plans that followed were even bigger.

Amazing Beavers

Aug 6, 2019 | | Notes from the WildThis serendipitous meeting with a near-sighted beaver was my favorite type of wildlife encounter!

Herons and Egrets

Sep 27, 2016 | | Notes from the WildHerons, egrets and bitterns are long-legged freshwater and coastal birds in the family Ardeidae.

Green Herons

Apr 7, 2015 | | BlogsHumans and other animals – not so different. Green herons will sometimes use leaves and other objects to lure fish within striking distance of their rapier-like beaks.

Vernal Pool Fairy Shrimp

May 5, 2015 | | Notes from the WildThese aquatic shrimp fairies are aptly named, for they are tiny, gossamer creatures.