Land Acknowledgments Decoded

A primer on the history and the reconciliation goals behind the statements read out before municipal, arts and sports events.

We’ve all heard land acknowledgments. Read aloud at everything from hockey games to municipal council meetings, these statements recognize the enduring relationships of Canada’s first peoples with their traditional territory. But what history lies behind the words? To find out, we parse two Headwaters land acknowledgments here.

Dufferin County Land Acknowledgment

We would like to begin by respectfully acknowledging (1) that Dufferin County resides within the traditional territory and ancestral lands of the Tionontati (Pétun) (2), Attawandaron (Neutral) (3), Haudenosaunee (Six Nations) (4), and Anishinaabe (5) peoples.

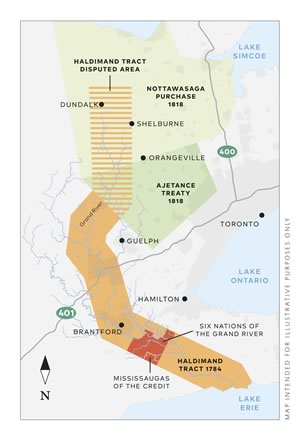

We also acknowledge that various municipalities within the County of Dufferin reside within the treaty (6) lands named under the Haldimand Deed (7) of 1784 and two of the Williams Treaties of 1818: Treaty 18: the Nottawasaga Purchase (8), and Treaty 19: The Ajetance Treaty (9).

These traditional territories upon which we live and learn are steeped in rich Indigenous history and traditions. It is with this statement that we declare to honour and respect the past and present connection of Indigenous peoples with this land, its waterways and resources.

1. Respectfully acknowledging the original and longstanding connection of Indigenous peoples to the land we all now occupy is central to land acknowledgments. But are these words sincere pledges that will bring about change? Or are they, as some critics contend, mere tokenism in lieu of meaningful action? The release in 2015 of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action highlighted 94 steps that must be taken to right centuries of wrongs and restore awareness of the defining role of Indigenous peoples in the history of Canada. The oral repetition of land acknowledgments is intended to promote mindful reflection, encouraging people to ask questions and educate themselves as a positive first step on the road to reconciliation.

2. The Tionontati, or People of the Hills, were called Pétun by early French fur traders. Most Tionontati lived in longhouses in walled villages southwest of Nottawasaga Bay in the lee of the Niagara Escarpment, but archeological evidence of a Tionontati village has been found as far south as northern Mulmur Township, and their hunting range included Dufferin County. As allies and trading partners of the Wendat, the Tionontati were nearly wiped out during wars with the Haudenosaunee (1649–50) over control of the fur trade. Survivors joined other First Nation refugees displaced by the wars and eventually migrated to present-day Oklahoma, where they formed the Wyandotte Nation.

3. The Attawandaron were based in the Hamilton-Niagara region, but their summer hunting camps extended north to present-day Grand Valley. Called “Neutral” because they lived in peace with both the Haudenosaunee and the Wendat, who were enemies, the Attawandaron were once the most populous nation of the Eastern Woodlands. But famine, European diseases and brutal wars over control of the fur trade dramatically depleted their numbers. Like the Tionontati, the Attawandaron dispersed, assimilating into other Indigenous nations. The pressures of colonialism and war ended their existence as a distinct nation.

4. Also known as Iroquois, the Haudenosaunee of the Six Nations of the Grand River near Brantford consist of the Kanienkahagen (Mohawk), Onondowahgah (Seneca), Guyohkohnyoh (Cayuga), Onundagaono (Onondaga), Onayotekaono (Oneida) and As Ska-Ruh-Reh (Tuscarora) nations. Their traditional territory was located south of Lake Ontario in northern New York State. During the peace negotiations that ended the American Revolution (1775–83), the British released these Haudenosaunee lands to the Americans without consulting Indigenous leaders. As a result, many Haudenosaunee migrated north to present-day southern Ontario.

5. Anishinaabe is the singular form of “Anishinabek,” an encompassing name for Indigenous nations that share similar languages and cultural traditions. Nations such as the Odawa, Bodaywadami (Potawatomi) and Ojibwe/Chippewa, including the Mississauga, are Anishinabek peoples. Their traditional territory extends from the Ottawa River Valley to the Great Lakes and into Saskatchewan. Active fur trading partners of both the French and British, Anishinabek nations often clashed with the Haudenosaunee. Treaty lands of both the Mississaugas of the Credit and the Saugeen Ojibway are located within Caledon, Erin and Dufferin.

6. For British officials negotiating early treaties, a treaty was a legal record of a real estate transaction that gave them ownership of Indigenous land in return for specific considerations. But Indigenous nations also had a long tradition of negotiating treaties with other Indigenous nations. Their oral tradition focused on the words spoken during negotiations, and the treaties were understood to be declarations of friendship and sharing between separate nations, not a surrendering of Indigenous sovereignty. These differing perspectives echo today in conflicts over the interpretation of treaties.

7. Hoping to protect their homelands from encroachment by settlers, most Haudenosaunee nations supported the British during the American Revolution. When defeated, the British purchased 950,000 acres from the Mississaugas in present-day southern Ontario. The Haldimand Deed (1784) granted this land to the Haudenosaunee, who had little choice but to accept. The Haldimand Tract extended six miles on each side of the Grand River from Lake Erie to the river’s source near Dundalk. But at the time, the British didn’t know the location of the source. Later, the British unilaterally excluded the northern reaches of the Grand, about 275,000 acres, much of it in Dufferin County. Today, a Six Nations land claim seeks compensation for this area.

8. The Nottawasaga Purchase (1818) included nearly 1.6 million acres purchased from the Chippewa nation in return for annual payments of £1,200 in goods. The purchase covered most of present-day Dufferin County, including the land the British had earlier excluded from the Haldimand Tract (see Haldimand Deed).

9. The Ajetance Treaty (1818), signed by Chief Ajetance of the Mississaugas of the Credit, released 648,000 acres of land for British settlement. Devastated by European diseases and forced off their land by settlers, the Mississaugas sold this land under duress. In return, the Mississaugas were promised annual payments of £522 in goods. The treaty territory included present-day Caledon, Erin, East Garafraxa and part of Orangeville, and like the Nottawasaga Purchase, land the British had earlier excluded from the Haldimand Tract.

In 2018, the Town of Caledon presented a wampum belt to the Mississaugas of the Credit to mark the 200th anniversary of the signing of the Ajetance Treaty. Indigenous nations used wampum belts to symbolize important agreements between peoples. Among its symbols, this belt shows two figures that represent Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals working together. Photo – illustration by Kim van Oosterom.

Town of Caledon Land Acknowledgment

Indigenous peoples have unique and enduring relationships with the land (1) Indigenous peoples have lived on and cared for this land throughout the ages. We acknowledge this and we recognize the significance of the land on which we gather and call home. We acknowledge the territory of the Anishinabek (2), Huron-Wendat (3), Haudenosaunee (4) and Ojibway/Chippewa peoples (5), and the land of the Métis (6). This land is part of the Treaty and Territorial lands of the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation (7). We honour and respect Indigenous heritage and the long-lasting history of the land and strive to protect (8) the land, water, plants and animals that have inhabited this land for generations yet to come.

1. For Indigenous peoples, the values of reciprocity, balance and respect are inextricably intertwined with their unique and enduring relationships with the land. But these relationships were brutally disrupted by colonization, with its forced relocations and territorial seizures, residential schools, compelled assimilation, and genocide. Land acknowledgments recognize that the ancestral and continuing connection of Indigenous peoples to the land is embedded in their cultural and spiritual identity. The Canadian Constitution affirms these relationships by acknowledging Indigenous peoples’ “Aboriginal rights” – inherent rights that flow from their ancestors’ traditions and culture. These rights may be different from the rights defined in treaties and can, for example, include the right to self-government.

2. Many Anishinabek nations have roots in Erin, Caledon and Dufferin County. After about 1650, when the Haudenosaunee drove the Wendat out of Ontario, the Odawa, Bodaywadami (Potawatomi) and Ojibwe/Chippewa, including the Mississaugas, began moving into present-day southern Ontario. By 1700, the Mississaugas and their allies had driven the Haudenosaunee back to their homelands in northern New York State.

3. Named Hurons by early French traders because of the way they wore their hair, the Huron-Wendat call themselves Wendat. Though most Wendat villages were located north, east and south of Headwaters, the land and waterways of Caledon, Erin and Dufferin made up the westerly reaches of the nation’s vast hunting and trading territory. By 1650, however, European diseases and the brutal trade wars with the Haudenosaunee had nearly wiped out the Wendat. Along with refugees from other nations, including the Tionontati, some Wendat migrated to Oklahoma. Others migrated to Québec, where the community of Wendake became their home.

4. The Haudenosaunee and the Mississaugas were rivals who had fought bitterly over territory in southern Ontario. But by 1847, the Mississaugas of the Credit River area were in dire straits. Ravaged by European diseases and facing continued encroachment by settlers, who had depleted the area’s game, fish and wood, they could not sustain their traditional way of life. So the Haudenosaunee, recalling that their home on the Haldimand Tract had been purchased from the Mississaugas, offered them territory on the tract. This became the new home of the Mississaugas of the Credit, and the two nations formed a close relationship.

5. Closely related to the Mississaugas through shared language and cultural traditions, the Ojibway/Chippewa are Anishinabek peoples who ranged through the present-day Headwaters region after migrating in the late 1600s to the territory of the dispersed Wendat, Tionantati and Attawandaron. During the fur-trade era, the Ojibwe and Chippewa often acted as “middlemen” between Europeans seeking furs and more distant Indigenous nations eager to trade the furs they had harvested.

6. Métis people consider themselves to be a unique Indigenous nation. They trace their ancestry to marriages between Indigenous women and European men. These marriages often helped facilitate the expansion of the fur trade, and distinct Métis communities arose in which the two cultures mixed to create a unique history and identity. Efforts have been made to strengthen the Métis language, Michif, and encourage its use by Métis people.

7. The Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation originally migrated from the Mississagi River area on the north shore of Lake Huron. Many believe the name “Mississauga” originated in their association with the river. After about 1650, many Mississaugas began migrating south, gradually pushing the Haudenosaunee back to their homelands in northern New York State. Mississauga territory covered a large area radiating outward from the western end of Lake Ontario and included Caledon and Erin. The mouth of the Credit River – the name “Credit” reflects the European approach of using credit when trading with Indigenous people – was an important focus of the Mississaugas’ trading relationships and became part of the nation’s name.

8. Commitments to strive to protect the natural environment, as well as to honour and respect Indigenous heritage, suggest good intentions. And both the federal and Ontario governments have enshrined in law a “duty to consult” Indigenous peoples when government actions affect their inherent or treaty rights. Caledon and the Mississaugas, for example, have worked together to develop a protocol to seek and incorporate Indigenous perspectives into town policies and planning. But it remains to be seen whether protocols such as this will translate into the sincere and meaningful engagement necessary to open the way to true reconciliation.

More Info

- Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation, mncfn.ca

- Dufferin County Cultural Resource Circle, dccrc.ca

- Indigenous History and Treaty Lands in Dufferin County, a history prepared by the Museum of Dufferin, available at dufferinmuseum.com

- Town of Caledon: A Guide to Meaningful Engagement with Indigenous Neighbours, a municipal protocol for consulting with the Indigenous community.

Note: Land acknowledgments are living documents, subject to change as additional research and perspectives become available. The wording presented here reflects the Dufferin County and Town of Caledon land acknowledgments as of March 2022.

Pronunciation Guide

Haudenosaunee (Six Nations)

“Ho-DEE-no-Sho-nee”

The Haudenosaunee or “People of the Longhouse” are a confederacy of six nations: the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Tuscarora, Oneida and Mohawk.

Anishinaabe

“Ah-NISH-IH-nah-bay”

A term describing a group of culturally related peoples. Some groups that identify as Anishinaabe are the Ojibway (also called Ojibwe, Ojibwa or Chippewa), Odawa (Ottawa) and Mississaugas of the Credit.

Attawandaron (Neutral)

“At-tah-wahn-da-ron”

Also referred to as Attiwandaron/Attiwandaronk.

Tionontati (Petun)

“Tee-oh-nahn-TAH-tee”

Also commonly referred to as Tionontate, Tionontatehronnon, Khionnontateronnon.

Related Stories

Meet the Maker: Kristin Evensen

Mar 31, 2021 | | Made in the HillsThis Orangeville artist strings together her Anishnaabe heritage and contemporary design in every pair of earrings she makes.

A Time for Listening

Sep 24, 2021 | | Headwaters NestCovid has forced us to work in new ways amid absurd family pressures. But coincident with the pandemic, we have been also confronting broader issues.