Home Child

Children were expected to work, often in the cruellest of conditions. Destitute, abandoned or orphaned, many children survived by their wits on the street.

More than 100,000 poor children and orphans were sent to Canada during the upheaval of Britain’s industrial revolution. More than a century later, their stories are finally being told. The story of one young emigrant and her lost family comes to Erin this fall.

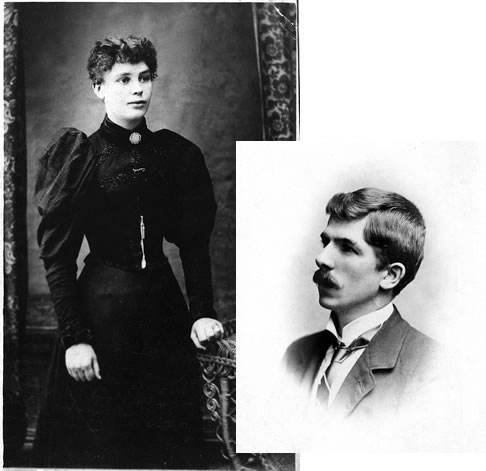

This picture of young Hilda Williams was taken on the day she entered a Barnardo home, which photographed and assigned a number to each child in its care.

“Who will love my boys, treat them as their own… Who will love my girls… keep them safe and warm?” laments Ellyn Griffyn, the heart-broken Welsh mother in Barb Perkins’ production Home Child: A Musical Journey.

Shrouded in sadness. That’s how Barb Perkins remembers her grandmother. Widowed too soon, having to work hard all her life, a loving but distant grandmother.

As a child, Barb always had a feeling there was some-thing more to her Nana’s dark glasses, terrible migraines and gnarled hands aching with arthritis. A secret.

No one ever talked about Nana’s childhood in Wales. No one ever asked. Somehow Barb and her siblings knew not to.

Then one unforgettable day in 1984, Barb learned the truth and began a journey that has led her to write and produce Home Child: A Musical Journey, which premieres in October in Erin. It is loosely based on her grandmother’s life as a home child, one of more than 100,000 children who were sent to Canada from the British Isles between the 1860s and 1939 to work as domestic servants and farm hands. It is estimated that millions of Canadians are among their descendants.

That day in 1984 Barb was standing in the driveway at her farm outside Hillsburgh, saying goodbye to her mother who had come to visit. Barb had two toddlers at her feet and a baby in her arms. Her grandmother had been dead for nearly a decade.

“We started talking about the family background because when you’re a new mom, you suddenly appreciate how much work your parents went through to raise you. I asked, ‘What about Nana?’ That’s when it started to come out.

“My mom said, ‘It was so sad. They were taken away from their family, put on a boat and sent to Canada, then separated when they got here. You should see the pictures of those poor little kids.’

“I could hardly believe what I was hearing. It never left me after that. I just had to find out more.”

What Barb learned was that Britain began to send children to the colonies in the nineteenth century because of the economic and social upheaval caused by the industrial revolution. People left the land to work in factories and mills, but the cities couldn’t handle the surge in population. Living conditions were squalid, overcrowded and unhealthy. Children were expected to work, often in the cruellest of conditions. Destitute, abandoned or orphaned, many children survived by their wits on the street.

The British Poor Law, in place in some form since the reign of Elizabeth I, gave local parishes the authority to force the unemployed poor into the dreaded workhouses. In 1834, the law was amended law to allow parishes to organize their emigration.

For the most part the emigration activities were well intentioned. An evangelical revival in Britain in the 1860s inspired such Christians as Annie Macpherson, William Quarrier, James Fegan and Thomas Barnardo to start humanitarian agencies to improve the lot of poor children. Thomas Barnardo became the best known in Canada, however his homes were among many that worked with emigrant children.

The equation seemed simple enough. British orphan-ages, asylums and workhouses were full. Canada and the colonies needed labour. Emigration was a solution. As one bureaucrat wrote in 1915, emigration became “the golden bridge” by which thousands of children “passed from an apparently hopeless childhood to lives of useful service and assured comfort in this new land.”

In 2003, genealogist Marjorie Kohli, of Waterloo, Ontario, published a comprehensive history of Canada’s young immigrants. In The Golden Bridge, she recounts that many children did go on to a better life in Canada, but that a significant number were “deprived of education and the comforts of family life.” Many suffered loneliness, prejudice and abuse.

“Even though the government placed a great importance on the immigration of these young people, the Canadian public did not always see it in the same light and some negative impressions were formed,” Marjorie Kohli writes. “The stigma attached to these children came through no fault of the children, but rather from the ignorance of the Canadian population of the time. Children were scattered across Canada by the thousands much as one would sow a field of wheat and, while the yield was plentiful, it was not without its problems.”

Ashamed of their roots, home children like Barb’s grandmother buried their past and their pain and, in the process, passed it on to the next generation.

Barb’s father only began to talk about his mother’s life a few years before his death in 1998. “I think he felt a lot of pain for his mom,” she says.

Barb’s father salvaged this tile, the only memento of his mother’s childhood, from her family home in Wales.

Barb produces a carefully framed antique fireplace tile to illustrate her point. In 1975 Barb’s father visited his mother’s old family home in Wales. The house was in the process of renovation with the living room scheduled for demolition the next day. Her father was drawn to a tile on the fireplace, three feet above the living-room floor. It depicted a swan swimming among the reeds. Barb’s father knew immediately he had to have it; he was sure it was something his mother and her siblings would have touched on rainy days when they played indoors by the fire. The swan tile remains the only personal memento from Hilda Williams’ Welsh childhood. Yet Barb only learned its story in 1990.

Today this is what she knows of her grandmother’s life:

Hilda Williams was born in 1898, a middle child among the nine children of Robert and Lewsia Williams. Robert was a dockworker, not a wealthy man, but from photos it is apparent the family was clean, well fed and well housed. They lived in one of the many stone row houses that still line the streets of Newport, near Cardiff, Wales. They were Church of England. The children attended school.

On the second of March, 1906, Hilda’s father was struck by a piece of timber at the docks and killed. Hilda’s mother was 31 at the time and pregnant with her ninth child. The eldest girls were 11 and 12. There was a year-old baby girl and a little boy of maybe three. Hilda would have been eight. There were two brothers just below her in age and one sister just above – the middle children.

Barb knows this from letters from the Barnardo institution, which still operates as a charitable organization in England. By 1901, there were 96 Barnardo Homes in Great Britain and four in Canada. It was a Barnardo Home that claimed her relatives. They kept meticulous records; each child was photographed and assigned a number.

Lewsia williams kept her family of nine children together for a year after her husband, Robert, was killed in an accident in 1906.

In the official report, the Barnardo ‘relieving officer’ spoke of Lewsia Williams as “a striving, respectable woman who elicited much sympathy.” The ten shillings a week in relief she got from the parish was paid away in rent. Her attempt at setting up a business with one of her brothers trading in fruits and vegetables failed.

“Still,” her great-granddaughter notes, “she managed to keep the family together for a whole year. It was somebody from the parish who said, ‘I’m going to see if I can get help for you.’ That’s when Lewsia was approached by the orphanage.”

The lady from Barnardo’s must have been as convincing as Barb’s great-grandmother was desperate. Lewsia had no intention of giving up her four middle children permanently; the arrangement was to last only until she could get back on her feet. The two older girls would look after the younger three while she worked.

The family would never be whole again. Someone somewhere in the Barnardo organization made the decision that the four Williams children, ages six to ten, should be included with a group of orphans scheduled to emigrate to Canada in 1907.

In 1990, when Barb went to Wales to do more research, people who knew the family described the way it had been ripped apart. They said Barb’s great-grandmother never got over it. Even in her old age, after she had remarried and had a tenth child, she still wept for her four lost children.

In Canada the children were separated. One boy was shot (but survived) trying to run away. One sister seemed to have fared fairly well. The other did not. Barb learned that her grandmother was treated roughly, passing through four different homes. Out of respect for her memory, Barb does not elaborate on the painful details of her grandmother’s story.

That’s why, too, in the musical, she’s changed the names of the characters and the time line; she’s concerned that some family members may still be sensitive to the public exposure of the family history. But, says Barb, Nan Griffyn is Hilda Williams.

In Canada, Hilda Williams experienced difficult times. The little immigrant passed through four different homes.

In real life, Hilda did eventually find her Canadian siblings and for a time they all lived together as young adults. Relatives in Wales remember receiving packages from them. Barb also knows that, as a young woman, Hilda went back to Wales to visit her mother. Relatives remembered how smartly she was dressed. No matter how modest her means, Barb says, “my grandmother was always stylishly turned out.”

Hilda married Arnott Hanenberg, an architect, and they had two children, Vivian and Arnie Junior. Then her husband died. He was only 45.

“I think that was another thing that made me feel so deeply for my grandmother. She had such a horrific childhood as a home child and then she fell in love, was married, and was widowed too soon.”

Barb is linked to her grandmother in another, more profound way. Barb and her husband, John, were devastated when their eldest child suffered brain damage from meningitis in 1981.

“For me, raising a disabled child who became more disabled as the years went on became enmeshed with writing my grandmother’s story. As my emotions deepened, I was able to get deeper into her story. It answered a lot of questions about my childhood and how I related to my dad…The more I knew and the more I wrote about my grandmother, the more cathartic it was for me.”

Barb had been a music teacher before she had her children. “I knew this was a story that could be put to music because of its Celtic roots, because it had such a Welsh flavour to it. I got immersed in Welsh music when I went over there in 1990 and came home with all these tapes of Welsh male choirs. I realized music is in their soul. I think I picked up a bit of that. It’s genetic.”

By 1997 Barb had written her grandmother’s story in song. It was accepted by the Charlottetown Festival in 1997 to be workshopped as a new Canadian work. Jackie Maxwell, current artistic director of the Shaw Festival in Niagara-on-the-Lake, directed the workshop. For two intense weeks it was sung and critiqued by day, while Barb reworked it at night.

“The piece that will be performed this fall in Erin is almost unrecognizable from what it was in Charlottetown,” she says. Characters and scenes were dropped, continuity and narration were added. The musical was pared down to the essence of the home child story: that love will lead you through almost anything in your life.

“I’ve learned that,” says Barb. And she is only half joking when she says that, second only to her children, her life’s work is to see Home Child: A Musical Journey produced on stage.

After Charlottetown, Barb always thought a theatre company would pick up the play. But after a couple of rejections, she decided she would do it herself. And so Stonehome Productions was born – run on a shoestring budget and driven by more than 80 volunteers from Erin, Hillsburgh and Orangeville. Nick Holmes of the Erin Community Theatre is directing and Brett Girvin, a music teacher at Erin District High School, is orchestrating the work. Thirty-six actors will perform twenty-three songs played by an eight-piece orchestra.

As well as writing the music and the story, over the years Barb has collected the props and the costumes, scrutinizing everything for authenticity. That’s why there will be no polyester on stage, and when they spin the bottle on the docks, the bottle says Cardiff right on it.

Barb Perkins and her daughter, Briar, amid props for home child, including a trunk that accompanied a child from the Barnardo homes to canada. Briar will play her own great-grandmother in her mother’s musical production. Photo by Tom Partlett.

Barb also found a real Barnardo trunk. It’s covered with imitation alligator skin and the name Miss Blanche Jordon is scrawled twice in pencil inside the lid.

When Guelph actor Heather Buck appears on stage as Ellyn Griffyn, she’ll wear a gold watch worn by Barb’s real great-grandmother.

It’s all part of what she calls the “genetic energy” of this production.

Barb’s 23-year-old daughter, Briar, will be playing the part of Nan Griffyn. “This was not written with Briar in mind. I thought this would have been produced many, many years ago. She was too young then to be involved. But she auditioned and auditioned well. She’s got the look, the hair colouring and bears a resemblance to her great-grandmother. I think there’s something karmic about this.”

When the play opens at the Erin Centre 2000, two second cousins from Wales and Barb’s 86-year-old Aunt Viv (Hilda’s daughter) will be in the audience. “I just hope it won’t be too hard on her,” Barb says.

Coincidentally, two other plays on the subject of home children are being produced just as Barb Perkins presents hers. Doctor Barnardo’s Children ran for a month this summer on the barnyard set of the 4th Line Theatre, near Peterborough. In January, 2006, CanStage is premiering Joan MacLeod’s play Homechild at the Bluma Appel Theatre in Toronto.

“At first I was taken aback,” admits Barb. “I’d been working on this for so long. Then I thought, no this is good, the home child story is being told on stages in Peterborough, Toronto and Erin.

“This is a story that needs to be told and retold,” she says, not only because it is a neglected part of Canadian history, but because even today bureaucratic expediency, economic hardship and misplaced political priorities still combine to deprive too many children of the secure and caring environment they need in order to thrive. Barb notes the recent example of the Romanian girl who was adopted by Canadian parents then rejected and sent back to her old country without an identity or the resources to rebuild her life.

Now that the musical is happening, Barb Perkins feels she can put her grandmother’s spirit to rest and move onto other things.

“I know she’s saying thank you for remembering us. I can feel it.”