The Beautiful and Damned – Dying Trees

Ash is doomed. Beech and butternut hover on the brink.

In the early decades of the 20th century, chestnut blight swept across the eastern United States and southwestern Ontario. The American chestnut, with a trunk as imposing and straight as a Greek column, was either killed outright or reduced to anemic sucker growth sprouting from stumps. Once a dominant tree, its departure left gaping wounds in the forest. North Americans lost a valuable timber tree, and wildlife lost its plentiful and nutritious nuts.

I was recently delighted to discover that American chestnuts grow in Headwaters at the Little Tract, one of 13 tracts that make up Dufferin County Forest. The chestnut trees at the Little Tract are small but undeniably healthy.

American chestnuts never grew naturally in these hills. They hugged the Lake Erie shore and the west end of Lake Ontario. That’s one reason the Little Tract’s trees are healthy. Their distance from the American chestnut’s natural range protects them from the blight.

The chestnuts of the Little Tract, refugees from southern deciduous forests, have found sanctuary in Dufferin County. Ironic, then, that they grow alongside several species of native Headwaters trees that may soon join the chestnut in the annals of arboreal disaster stories. The three species of ash that grow here – red, white and black – are succumbing to the emerald ash borer. Beeches are under assault from beech bark disease, and butternuts are falling to the butternut canker.

Elm, of course, merits inclusion on this doleful list. After the American chestnut was effectively destroyed, it was elm’s turn. Some of my earliest childhood memories are of majestic elms, denuded and debarked, awaiting the chainsaw.

Like American chestnut, elm is the victim of an introduced fungus. This fungus piggybacks on a variety of elm bark beetles to get from tree to tree. Yet some large elms have survived. Perhaps their genes offer hope they are resistant to Dutch elm disease. More likely, they’ve just been lucky – the beetles and fungi haven’t found them yet.

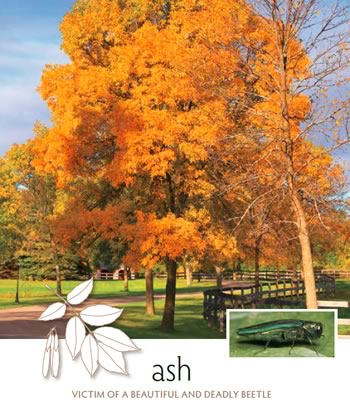

Ash

Victim of a beautiful and deadly beetle

The loss of the elm changed Ontario’s visual landscape, for it was a common tree, frequently planted along streets and as shade in farmers’ fields. Of beech, butternut and ash, the loss of ash will have the greatest visual impact. Ash is abundant in our towns and villages. It hugs roadsides and is a common tree in most Headwaters woodlands. We will notice its loss.

The loss of the elm changed Ontario’s visual landscape, for it was a common tree, frequently planted along streets and as shade in farmers’ fields. Of beech, butternut and ash, the loss of ash will have the greatest visual impact. Ash is abundant in our towns and villages. It hugs roadsides and is a common tree in most Headwaters woodlands. We will notice its loss.

A trip along the 401 in southwestern Ontario offers an idea of what Headwaters can expect as the emerald ash borer makes itself at home here. Swaths of the deciduous woodland visible from the highway have been laid waste by this insect – and the devastation has arrived here. Dead and dying ash can now be seen along most of Caledon’s rural routes.

This ugly work is done by a lovely iridescent green beetle. The emerald ash borer’s larval grubs burrow into a tree, settling just beneath the bark in its circulatory system, called the cambium layer. Here, the grubs create a network of tunnels, effectively choking off the flow of water and nutrients. Death comes quickly.

The spread of the emerald ash borer has been blindingly fast. First detected in the Detroit-Windsor areas in 2002, it now feasts on ash across most of eastern North America. By last year, Credit Valley Conservation had found it throughout the Credit Valley watershed, from Orangeville to Lake Ontario. If it is not yet in other parts of Headwaters, it soon will be.

One component of CVC’s emerald ash borer management plan is inoculating selected ash trees with an insecticide called TreeAzin. Injected through holes drilled in ash trunks, close to the ground, TreeAzin offers hope that at least some ash trees can be saved.

But regrettably, it’s clear this treatment will save only a tiny minority of ashes. At about $550 a litre, which may be enough to inject two large or four medium-sized trees a year, TreeAzin is expensive. And the cost of injection equipment and a licensed pest control specialist to administer the treatment must also be factored in.

The emerald ash borer is as beautiful as it is destructive. Bores in the bark are early evidence of beetle infestation. Photo by Robert McCaw.

What’s more, TreeAzin isn’t a one-shot solution. Kevin De Mille, an invasive species management technician with CVC, outlines the preventive regime: “In areas where the emerald ash borer is already well established, CVC injects the insecticide in back-to-back years and then every other year thereafter for a period of 10 or 12 years.” So saving ash trees is costly, but as De Mille notes, it might make sense in some situations.“Yes, it’s a lot of money, but put against the value of a large tree, it could be worth the investment.”

For landowners who want to explore this possibility, De Mille’s advice is to hire an arborist. “An arborist will assess your trees and determine the available options. They will recommend pesticide injection or tree removal. But ash need to be injected before there are signs of decline. A thinning canopy may indicate the emerald ash borer has already infected the trees. If that’s the case, they’re likely too far gone.”

Another caution is necessary here. TreeAzin may protect your ash from the emerald ash borer, but it’s ineffective against other virulent pests and diseases that attack ash. Thus, inoculation requires money and faith.

CVC is now in the process of removing nearly 3,000 ash trees from its properties by next year, primarily those that present a hazard along trails. As for private properties, De Mille advises landowners, “Make sure your boundaries are safe. Make sure you won’t have trees falling on your neighbour’s house or fences, roads or hydro lines.”

Municipalities throughout Headwaters are also starting to remove ash trees as part of their urban forest management programs. John Lackey, Orangeville’s manager of operations and development, will oversee the removal of about 70 ash on Orangeville municipal properties this year. The project is part of a 10-year program to deal with the ash borer.

As with CVC’s removal plans, Orangeville’s program will be driven by attention to safety and liability concerns. “We make an assessment of the tree based on its size, proximity to utilities and structures, and the risk it poses to the public, concentrating on boulevard trees first,” says Lackey.

For residents concerned about ash trees on their properties, Lackey echoes De Mille’s recommendation that they enlist the assistance of a professional arborist.

Aside from cutting and inoculating selected trees, the Canadian government is piloting a biocontrol project at CVC’s Silver Creek Conservation Area north of Glen Williams in Halton Region. There, insects that parasitize emerald ash borer larvae and eggs have been released. Biological control, or biocontrol, isn’t the proverbial silver bullet, but it has reduced the damage in other jurisdictions.

Beech

Falling to a one-two punch

No biocontrols or pesticides are currently available to fight beech bark disease. Like the emerald ash borer and Dutch elm disease, beech bark disease arrived from overseas. Officially confirmed in Ontario only in 1999, it has since spread with the heartbreaking rapidity so characteristic of invasive tree pathogens and is now firmly entrenched in Headwaters and most of the rest of southern Ontario.

No biocontrols or pesticides are currently available to fight beech bark disease. Like the emerald ash borer and Dutch elm disease, beech bark disease arrived from overseas. Officially confirmed in Ontario only in 1999, it has since spread with the heartbreaking rapidity so characteristic of invasive tree pathogens and is now firmly entrenched in Headwaters and most of the rest of southern Ontario.

Beech bark disease hits beech trees with a one-two punch. First, a tiny scale insect, introduced from Europe, opens wounds in the bark. This may weaken a beech, but doesn’t usually kill it. What it does is open a passage to the inner bark and cambium layer for the microscopic spores of a canker fungus with the tongue-twisting name of Neonectria faginata. It is this fungus that kills.

According to the Ontario Forest Research Institute, part of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, 99 per cent of beeches are susceptible to this dual assault.

Despite this, Kata Bavrlic, a terrestrial monitoring specialist with CVC, remains hopeful beech bark disease will not cause mass mortality in the Credit Valley watershed. According to Bavrlic, 85 per cent of beech trees in the watershed show evidence of the scale, but only 16 per cent of the monitored trees appear to be suffering from the fungus as well. “Since we first noticed the scale in 2006-07, not much has changed,” she says. “The good side of the story is that it appears many of the trees are fighting off the disease, not succumbing to its effects.”

This may be true in parts of the Credit Valley watershed, and in fact, the healthiest beeches I found on my summertime rambles were in Forks of the Credit Provincial Park. But the situation at other Headwaters locations appears far more dire. At the Little Tract in Dufferin County, nearly all beech trees with a diameter of 15 centimetres (about 6 inches) or more are dead or dying. Like a disfiguring skin condition, the smooth grey bark has been corrupted by the scale insects. Branches in the canopy are dying, and many of the remaining leaves lack the lustrous green of healthy foliage.

Beech trees at Mansfield Outdoor Centre, just south of the Little Tract, appear to be similarly afflicted. These trees, in at least some parts of Headwaters, appear on their way out as a significant functioning part of the woodlands and this, for the environment and for unabashed tree lovers like me, is tragic.

Sylvia Greifenhagen of the OFRI told me, “We are starting the first steps towards a recovery program for beech. Some potentially resistant trees have been identified.” She added the hope that “seed orchards” from resistant trees can eventually be established “to produce seed for possible future planting.”

Greifenhagen’s advice to landowners? “Monitor your trees for the beech scale and the disease.” She advises removing heavily infested trees in areas where they pose a hazard to life or property. Where the trees don’t pose a hazard, preliminary research suggests the best approach to promoting the long-term health of beeches may be the “gradual removal of diseased trees, combined with regeneration management and retention of potentially resistant trees.”

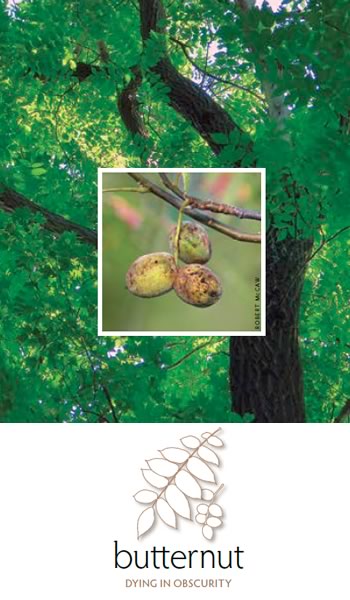

Butternut

Dying in obscurity

Butternut, another species in this trifecta of arboreal decline, can be thought of as the forgotten tree, dying behind the scenes, obscured by its scarcity and the panic over the very public decline of the abundant ash.

Butternut, another species in this trifecta of arboreal decline, can be thought of as the forgotten tree, dying behind the scenes, obscured by its scarcity and the panic over the very public decline of the abundant ash.

Few of us will notice as butternuts succumb to butternut canker, yet another tree-killing fungus. The provenance of this fungus, which discolours butternut bark with dark soot-like patches, is unclear, but as with other tree pathogens, an offshore origin is strongly suspected.

Butternut has been designated an endangered species in Ontario, and the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry has established strict rules governing whether they can be cut down. If healthy trees are removed, for example, they must be replaced by butternut seedlings.

Thankfully, the butternut has some staunch supporters despite its obscurity. One is Barb Boysen of the Forest Gene Conservation Association, a nonprofit group dedicated to conserving the genetic diversity of forest trees in south central Ontario. “I love this species,” says Boysen. “Its seeds are so nutritious – many creatures, including humans, appreciate them. Its wood is soft and beautiful and useful.” She refuses to accept the demise of this relative of the black walnut. “There is a lot that simple conservation can do for butternut and for all endangered species.”

An aspect of that “simple conservation” is encouraging landowners to tell the FGCA about their butternuts that may be resistant to the canker. “We rely on local people to tell us about their healthier trees, the ones surviving, though many around have died.”

Conserving butternuts can also mean thinning the canopy around healthy trees to give them greater access to the light they crave. It also involves taking “scions” – cuttings – from the crowns of butternuts that may be canker-resistant and grafting them onto black walnut seedlings in the hope they will eventually produce nuts that will, in turn, produce other canker-resistant trees.

Butternut cuttings like these have been planted at four butternut “archives” in southern Ontario. These archives might be considered butternut arks. They are lovingly tended by people like Greg Bales, who manages an archive near Glencairn in Simcoe County. I visited Bales on a hot June day as he prepared to do some weeding at the Glencairn site. Bales is driven to help the tree out of real concern for its future: “Butternut may not survive this disease. Extinction is a real possibility.”

Jim Laking, who owns property abutting one of the Dufferin County Forest tracts, has large, healthy butternut trees that provided some of the scions for the butternut saplings now growing in the archive nursery plots. When I visited Laking, he showed me an old journal that included this entry by a family member: “We collected bags of butternut to crack for baking and spread sheets under beech trees to collect beech nuts.” A poignant memory of a bygone time and one that illustrates the connection our forebears had to these trees.

The resistance movement: go native

We need to rebuild our connection to these threatened tress, especially in light of the reality that a host of other pests and diseases are approaching and may threaten our hemlock, black walnut, oaks and maples.

Particularly frightening is the prospect of a possible invasion by the Asian long-horned beetle. Two outbreaks have occurred in Ontario so far – the latest in 2013 in Malton, where 7,500 trees were removed in an effort to contain the insect. The Asian long-horned beetle has a diverse diet that, ominously, includes maple. With sugar maples our most common tree, let’s hope the containment effort has been successful.

If you cherish trees, you’ll be forgiven if you respond to all this bad news with despair. There are, however, things we can do to make the best of a bad situation. Learning about the role our native trees play in the ecosystem is a good place to start. Native trees are part of a complex, interdependent web of life that includes fungi, insects, birds and other animals that have evolved together over millions of years.

Scores of insects, including many moths and some butterflies, for example, depend on ash as a host tree. As ash trees are lost, so are many of these insects. If you consider the loss of insects good riddance, please think again. Insects are songbird manna. Caterpillars, in particular, are critical food for songbird young.

Realizing this underscores the importance of planting native trees to compensate for the trees we are losing. Native trees do a much better job of sustaining the environment than non-natives such as Norway maple.

Know, too, that beauty need not be sacrificed when going native. Our native trees are glorious and, in the full bloom of maturity, awe-inspiring. Native pines, oaks, hickories, maples and cherries are some of the wonderful trees that deserve pride of place in our towns and villages. Municipalities are climbing onside. Most of the tree species planted in Orangeville to replace ash will be native.

Caroline Mach, Dufferin County’s forest manager, fully supports this direction. “Species should be native to this part of Ontario, matched to site and soil conditions, and ideally come from a local seed source,” she says. Baker Forestry Services in Erin is one source of local stock. Whenever possible, owner Bob Baker and his family gather local seeds, nuts and fruit to grow into trees.

Planting a diversity of trees can also soften the effects of losing a single tree species. If one species succumbs to a pathogen or to changes in the environment, other species will be present to cushion the impact. The preponderance of sugar maple in many Headwaters woodlots worries me. Don’t get me wrong. I love sugar maple, but if efforts to stop the Asian long-horned beetle fail, the loss of sugar maples could be catastrophic. We need tree diversity throughout Headwaters.

If you are lucky enough to own a woodlot, the various Headwaters conservation authorities will provide expert advice on which trees to plant, and they will also supply those trees at a very reasonable cost. They will also help you deal with the emerald ash borer and other threats.

Finally, if you have space, consider planting the endangered butternut, but ensure you buy butternut sourced from trees deemed possibly resistant to butternut canker. Such butternut are available from Baker Forestry Services and Somerville Nurseries in Everett. Let’s leave a legacy of butternut for our children and grandchildren.

With our trees under unprecedented stress, it’s time to give voice to our inner tree hugger. We have a precious arboreal heritage to protect, now and for future generations.

Do you have a healthy butternut on your property?

If so, the Forest Gene Conservation Association would like to know about it.

Forest Gene Conservation Association

Suite 233, 266 Charlotte Street

Peterborough, Ontario K9J 2V4

[email protected]

For details of laws governing cutting down butternuts, see ontario.ca/environment-and-energy/butternut-trees-your-property

More Info

HEADWATERS TREE WALKS

Beautiful woodlands flourish in Headwaters and can be enjoyed by walking the Bruce Trail and a network of shorter trails in conservation areas and county forests. Here are a few special places where you can see the trees – healthy and otherwise – highlighted in this article.

GLEN HAFFY SIDE TRAIL

A blue-blazed offshoot of the Bruce Trail along Glen Haffy Road between Highway 9 and Coolihans Sideroad in Caledon. About 2 km.

Mature deciduous trees form a sylvan arch over Glen Haffy Road. Several butternuts, including two imposing specimens in excess of 70 cm in diameter abut the road. Ash are abundant, and a few beeches can also be seen from the road, though they are, regrettably, dead or dying. Here, too, grow lovely hemlocks, trees that may soon be under assault from hemlock woolly adelgid, another imported pathogen.

LITTLE TRACT

On the west side of Airport Road between 17 Sideroad and 20 Sideroad in Mulmur Township. About 2 km.

The Little Tract boasts a small planting of American chestnut, near the parking area. On their own, these healthy refugees from farther south make Little Tract a worthy destination. But do walk the trail. You’ll find a forest very different from much of Headwaters. Here on the Oak Ridges Moraine grow a diversity of trees in relative abundance. Sugar maple, overwhelmingly dominant in other areas, does have a presence here, but only as a minority shareholder. White pine, red oak and red maple are abundant.

BOYNE VALLEY SIDE TRAIL

In Boyne Valley Provincial Park on the west side of the First Line East between Highway 89 and 5 Sideroad in Mulmur Township. About 2 km.

Walk the side trail (blue blazes) to the main Bruce Trail (white blazes) and follow the Bruce Trail eastward back to the First Line and your car. I love this hike. The deeply incised dells, cooled and cloaked by large deciduous trees, mainly sugar maples, are truly magical. After turning onto the main Bruce Trail, start looking for beech trees. Several can be seen on the slopes here, including a venerable giant of transcendent beauty.

Related Stories

8 Ways to Kick Your Grass Habit

Mar 20, 2017 | | EnvironmentInspiring tales from those who broke free from the rule of lawn.

A Foraged Feast

Mar 21, 2016 | | FoodSkip the supermarket, find the ingredients for gourmet dining in forest, field and stream.

Amazing Beavers

Aug 6, 2019 | | Notes from the WildThis serendipitous meeting with a near-sighted beaver was my favorite type of wildlife encounter!

Beech Trees

Dec 10, 2014 | | Notes from the WildBeech trees are being destroyed at heartbreaking speed by an introduced pathogen called beech bark disease.

Bobolinks, Grasslands and Forks of the Credit Provincial Park

Jul 25, 2012 | | Notes from the WildBobolinks, though, are only one patch in the quilt of the glorious grassland ecosystem that exists at the Forks.

Butternut Canker

Feb 22, 2012 | | Notes from the WildMost of our butternuts are dead or dying, stricken by a fungal disease called butternut canker.

Take a Walk on the Wild Side: Forest Bathing

Mar 26, 2018 | | Good SportSlowing down, tuning in. With forest bathing, the slow movement takes to the woods.

Hi Carrie,

Thanks for your question. There are several species you could consider. Your decision, of course, will depend in part on how much space you have. If you have room you could plant a tree that will eventually achieve large dimensions. For Orangeville I’d suggest a red oak – long lived, glossy leaved, majestic. One of the largest red oaks I’ve seen is located on the front yard of a property on 2nd Street in Orangeville. Simply magnificent! Other worthy large trees would include hickories – unlike red oaks, not readily available from nurseries though and white pine and sugar maple. If sugar maple, ensure it’s not too close to the street where it may be affected by winter road salt. A good small tree is serviceberry. White flowers in spring, delicious fruit in summer (thought the birds will likely get it before you do.) One caution: if you choose to select a maple, please ensure it’s a native maple. Norway maples masquerade as natives and are the most common maples sold at nurseries. Nurseries offer multiple cultivars that often mislead purchasers: “Crimson King”, “Emerald Queen” etc. The problem with these? They offer nothing at all to our local ecology. Bugs – food for songbirds – shun them, and they escape into natural areas and take over.

Hope this helps!

Don Scallen

Don Scallen on Sep 23, 2018 at 9:24 pm |

I am just wondering what species of tree would be a good one to plant in Orangeville, Ontario, considering the prevalent diseases currently affecting trees in this area…Please advise.

Carrie from Orangeville on Sep 23, 2018 at 9:39 am |

I have been managing my woodlots most of my life, and my woodlots are my life. It is so very depressing, to see what is happening to my woodlots. I can’t help but think if we are eventually going to loose our native tree species, what’s the point in forest management? Most owners of woodlots will loose their motivation to work with their forests. God help us, this is a very sickening position for woodlots owners to be in. However for the vast majority of people who live in cities, towns, village’s and even rural people, probably the thinking is, oh well, I have my own problems, and do not give it much thought.

Douglas Dennis from East Elgin County, ontario on Nov 15, 2017 at 7:36 pm |