Obstacle Course Racing

Making sport of obstacles: A Caledon couple are rising stars in a challenging new professional sport.

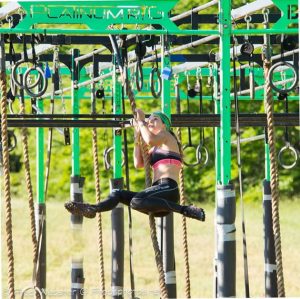

Lindsay Webster successfully toughs her way through the challenging Platinum Rig. Photos by Fred Webster.

On an early July morning I parked myself near the Platinum Rig. I’d been told it is one of the most entertaining obstacles on the Battle Frog race course at the Highlands Nordic centre near Duntroon.

Minutes later, Caledon resident Ryan Atkins sprinted to the massive stainless steel structure and took a flying leap to catch hold of the first set of rings hanging from the oversized monkey bars. He then swung Tarzan-like from ring to ring, vertical pole to vertical pole, to dangling rope.

Next he caught hold of a six-foot horizontal bar that tilted upwards. Hand over hand, his Johnny Weissmuller muscles glistening in the early morning sunshine, he made his way through the obstacle, which requires grip strength, a strong upper body and highly practised technique.

With a final swoosh, Ryan kicked the colourful metal bell to signal he’d completed the job, dismounted, and was off to negotiate a series of three water-filled ditches separated by mounds of dirt.

In about 90 gruelling minutes, Ryan would complete the required two laps of the 26-obstacle, 8.2-kilometre cross-country course.

Moments later, Ryan’s wife Lindsay Webster made her way through the same set of rings and bars, though they were set a little closer together in her lane to allow for women’s size. At five foot five and 112 pounds, Lindsay has the perfect physique for obstacle racing: light for running and strong for the Navy SEAL-inspired obstacles such as the Platinum Rig, jerry-can carrying, rope-wall climbing and sandbag slugging.

To a casual eye, the 27-year-old made it look easy. But a closer examination of Lindsay’s face revealed steely determination. After the race she explained that, like her husband, she trains for up to three hours and more a day, making great use of Caledon’s ideal terrain. “I love the hills,” said the Mayfield grad.

In a competition that is growing in popularity throughout North America, Ryan and Lindsay are stars. They are also professionals. Though Ryan has a degree in mechanical engineering and Lindsay specialized in both media studies and culinary management at university, they are now full-time obstacle racers. Part of the BattleFrog Pro Team and with more than a half-dozen sponsors between them, the ultrafit pair say they can afford to devote all their time to the sport. Says Ryan, “It’s a lot more fun than sitting behind a desk all day.”

On that July morning the couple didn’t disappoint the hometown crowd. Ryan and Lindsay were the fastest man and woman on the course. Although Lindsay ended up without a prize (see endnote), their performance was proof their status near the top of the obstacle course racing heap is no fluke.

The couple dominates a sport dominated by Americans – and organized by privately owned firms including BattleFrog and Spartan. Lindsay’s finish put her in a good position to defend her 2015 victory in the Obstacle Course Racing World Championships, which take place in October at Blue Mountain near Collingwood. And Ryan is looking forward to improving on last year’s second-place finish in the men’s elite division.

Though Ryan and Lindsay made the course look deceptively easy, Orangeville native Sharlene Kottelenberg shed a different light on a sport that offers an alternative take on adventure racing. The 33-year-old petite blonde set off on the course at 7:15 a.m. with the other elite athletes. And like all competitors, she’d had to get down on one knee at the start line and listen to the fatigue-clad, microphone-wielding starter give a military-style pep talk. “How hard are you willing to push?” he asked. “Look deep into yourself for mental toughness. Look inside your soul,” he advised, sliding up half an octave as he stretched out the word “soul.” “Who says we’re not brothers and sisters in battle?”

BattleFrog is sport as big business. The company will hand out $1 million in prizes over the 2016 season. First prize for the elite man and woman in the Duntroon race was $500 each.

But the sport is more than just a series of arduous races for elite athletes. It promotes a lifestyle that can be embraced at many different levels, from rank beginners to families with children to professional competitors such as Ryan and Lindsay. The Spartan website, for example, outlines the “Spartan Code” and describes the company as a “community, a philosophy, a training and nutrition program – with daily advice, a podcast, a series of books, an activity for kids, workout gear, a media channel, an NBC Sports series, a digital magazine, and a timed obstacle race.”

When I asked Peter Hering, director of the Duntroon event, what obstacles I should watch, he told me the most entertaining ones were nearest the food tent. Smart planning for camera crews and spectators who had coughed up $30 to take in the show.

Sharlene Kottelenberg ruefully displays the battered hands that forced her to give up – but she’ll be back. Photos by Fred Webster.

Back at the crowd-pleasing Platinum Rig, Sharlene stood staring at the apparatus. There was something about the set of her jaw that caught my eye. Behind me, I could hear the high-pitched voices of her children cheering on their mum.

Sharlene jumped, caught the first ring, and the second, then swung herself through the vertical poles to the tilted horizontal pole and made her way along it – halfway to the end. Coiling her foot in a rope and grasping a ring, the mother of three stopped to regroup. She’d need Tarzan skills herself to get a handhold on the next horizontal bar. It seemed miles away for such a petite woman. “You can do it, Mum!” her brood called out.

She got the rope swinging and in this way managed to catch hold of the next bar. But then she dangled limply, her momentum stopped. Using brute strength, she tried to make it to the next fixed horizontal bar, but there was no way. Her hands slipped and she dropped to the straw-covered ground. Sharlene had the will, but not yet the technique.

Given race rules, she would have to start the obstacle over again, and unless she completed it without error, she would be disqualified: no points, no prize money, no bragging rights. Jaw set, she walked back to the start. “You can do it, Mum!”

For the next hour Sharlene tried again and again to master the Platinum Rig – and she wasn’t alone in her repeated attempts. Sometimes she made it back to the rope, sometimes not. Eventually her determination cracked. She glanced at her husband and kids, whose cheers had changed to “Mum, you already have enough points to get into the Worlds.”

Finally, and though it was technically possible for her to keep trying all day (one elite competitor told me she had once spent seven hours at a set of monkey bars), Sharlene sat down beside her husband with her hands extended, palms up. They were blistered and bloody.

The last I saw of Sharlene, she was seated in the first aid tent, her trio of tow-headed kids hanging from her as though she were a Platinum Rig. They seemed unfazed by their mother’s gallant though failed attempts to complete the obstacle. I imagined they were whispering in her ear, “You’ll do better next time, Mum,” though they were more likely asking, “Is it lunchtime yet?”

Note: In a strange twist, Lindsay and a teammate were disqualified from the race because they inadvertently completed the wrong – and less difficult – lane through an obstacle. Though no one had witnessed their error, the two voluntarily went to race officials and explained their mistake, which meant forfeiting their points and prize money. Admirable behaviour in an increasingly businesslike sporting world.

Learn more about obstacle course racing

- The Obstacle Course Racing World Championships

- Spartan

- As In the Hills went to press, BattleFrog announced they were cancelling their long-course races and indicated they were no longer sponsoring Lindsay or Ryan. The world-class duo is currently assessing the opportunities before them so stay tuned.