A Community Mourns

In the winter of 1946 the people of Bolton were drawn together by an incident that began with all the ingredients of a grand farce, but ended in tragedy.

In the winter of 1946 the people of Bolton were drawn together by an incident that began with all the ingredients of a grand farce, but ended in tragedy.

The narrative is simple. At 1 a.m. on Sunday, January 27, Leonard Gott saw two men preparing to break into the Imperial Bank of Canada in the centre of Bolton. He ran home and alerted his father Cecil, who telephoned town constable Ed Ewart. Both Gotts, father and son, then grabbed rifles and returned to the bank where the unusual nighttime noises had already drawn neighbours to the street.

Leonard Gott was returning home from spending the evening with Gwen Hardwick that fateful night.

The robbers, aware they had been discovered, fled the scene, pursued by an ad hoc posse with Leonard in the lead. Cecil Gott fired at the bandits but hit his son, a diversion that disrupted the chase and allowed the culprits to escape. Leonard was thought to be just slightly wounded but died in hospital 14 days later. He was 19 years old.

It should have been a comedy

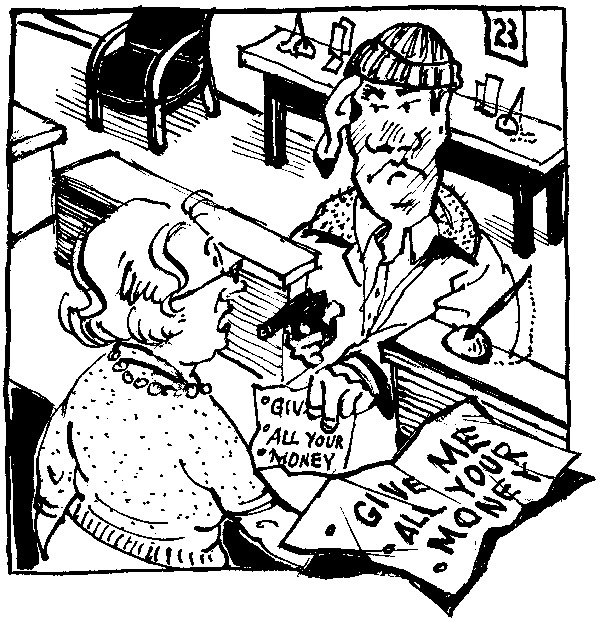

The two bank robbers, it turned out, had prior criminal experience, but this attempt to rob a bank was clearly a first-time venture. Earlier on Saturday night they had broken into a garage in Toronto and stolen oxy-acetylene tanks and a cutting torch, which they transported to Bolton in a car they stole near Maple Leaf Gardens while its owner was at the Leaf game.

So far so good, but once in Bolton, in plain sight of Leonard, the two parked the car right in front of the bank where one of them then made sure they were noticed by banging his head on a street sign and shouting an oath, ensuring the witness was completely focused as they dragged their stolen equipment – four-foot tanks – to a side door of the bank.

While Leonard ran home to his father, the pair woke nearby residents by noisily smashing a cellar window. Once inside they opened the door, hauled in the equipment and lit the torch, which further advertised their presence by sending a beacon of light through the newly broken window.

Among those roused by the clatter was William Maw. In a hurried telephone conversation with the bank’s accountant, he was told the alarm was disconnected that weekend and was urged to go out on the street and fire his shotgun into the air. The robbers’ response to this substitute alarm system was simply to cover the window with a blanket and carry on with the cutting torch.

No longer funny

What had been a cartoon-like situation now shifted dramatically. Finally aware they had been discovered, the bandits emerged through the broken window just as Constable Ewart arrived. For some undisclosed reason, Ewart parked farther down the street, so with the gathering watchers also keeping a sensible distance, the pair had space to start their escape by sprinting toward the Humber River. (They ran first for their stolen car but changed direction when William Maw fired into the air again, this time with effect.) Leonard was first to react to their escape and it was while he was leading the chase that his father’s errant rifle shot took him down. The pursuit came to an immediate halt beside the fallen young man and the robbers got away – temporarily.

The safecrackers’ car abandoned in front of the Imperial Bank in Bolton.

Leonard was carried into a nearby residence (the Maw home) and as soon as the steadily growing crowd was assured his wound was minor, attention returned to the pursuit. According to the Orangeville Banner, every able-bodied man in Bolton eventually joined the chase, along with farmers within a 20-mile radius of town, all recruited in a flurry of telephone calls.

In the darkness, pursuers followed a clear set of tracks in the snow that led across the frozen Humber and into open fields north of town, but once the tracks emerged onto the packed surface of Highway 50, the chase petered out. The OPP took over in daylight, their search given direction by some obvious clues and the fact Leonard was certain he’d recognized one of the robbers, a young man from Palgrave. Police arrested the pair the next day. Conveniently, they had gone home.

The community responds

With the provincial police in charge of the robbery, the town’s focus turned to the condition of Leonard Gott. What was originally thought to be a flesh wound turned out to be more serious, and by Sunday noon the whole of Bolton was aware an ambulance had taken Leonard to hospital in Brampton for surgery and a series of blood transfusions.

The acetylene torch used by the safecrackers. Courtesy of Toronto Public Library and The Globe And Mail.

By evening, several carloads of Bolton citizens had voluntarily presented themselves at the hospital to donate blood, but were relieved to be turned away with the news that Leonard’s condition had stabilized. Sadly, things didn’t stay that way. As the days passed it became apparent the young man’s continuing loss of blood was beyond the reach of 1946 medical skills.

According to newspaper reports and attestations by Leonard’s nurses, virtually the entire population of Bolton (c. 600) offered to give blood in the days before he died. That same population, increased by hundreds from the countryside around, attended what was described as the largest funeral Bolton had ever seen. The community had lost one of its own in a sad, ironic way that could not go unacknowledged.

Aftermath and afterthoughts

It’s no surprise that an inquest a month later strongly condemned “the use of firearms by citizens in helping to discharge the duties of police officers.” Medical testimony called it “fate” that the bullet struck the young man where it did, while Peel’s coroner remarked that Leonard’s hasty pursuit was an example of “the youthful incaution demonstrated many times during the war” just ended. None of this could have eased Cecil Gott’s profound remorse (he was too ill to attend the inquest) any more than the verdict: accidental death. He was already a widower, and now had lost his only son.

There’s little question that in this incident guns appeared on the street – and were fired – far too readily. And it’s easy to say Leonard and his father should have waited for a police response. But this was a small town in 1946. The Gotts knew a police response at 1 a.m. on a Sunday morning was not going to be instant, and this was their town, their bank.

Probably as important, just the previous year, Cecil Gott had been Bolton’s highly regarded reeve (and warden of Peel County). Holding an office of such responsibility meant that for him reacting instantly to a serious crisis in his town was automatic. Had Leonard’s wound been as minor as first thought, the entire event would soon have been forgotten. But what medical testimony called “fate” converted a responsible citizen’s hasty best intentions into sorrow for himself and everyone in the community.

A book featuring more than 40 of Ken Weber’s columns will be published this fall. The official launch of Ken Weber’s Historic Hills: Stories of Our Past from In The Hills takes place October 15, 2 p.m., at Dufferin County Museum & Archives. Ken will also be signing books at Forster’s Book Garden in Bolton on October 14 and at the old Alton school on September 30 as part of Culture Days. Ken will also emcee Canadian Beer & Trivia night at DCMA on the evening of September 23.

More Info

Reporting the news inside and outside the community

The story of a father shooting his son, accidentally or otherwise, is newsworthy, and national wire service meant accounts appeared in journals as widely dispersed as the Winnipeg Free Press, the Lethbridge Herald and the Halifax Mail. The Toronto Daily Star carried a full report and The Globe and Mail sent reporters and a photographer to Bolton (which it called “a little village”). As for weekly papers in the hills, the Orangeville Banner offered a thorough, quite restrained report as did the Erin Advocate, while the Brampton Conservator opted for drama.

Few out-of-town papers bothered to report on the sentencing of John Reynar of Palgrave (two years less a day) and a 16-year-old from Toronto (probation). Perhaps such news was too ordinary. On the other hand, almost every account made a big deal of the father-shoots-son irony and highlighted an element of pathos that, given Leonard’s eventual death, must have been gut wrenching for local citizens to read.

When the young man was shot, he crawled toward his father who, shocked by what he’d done, shouted in disbelief, “You’re not Leonard!” To which his son replied, “Was it you that shot me, Daddy?” In its extensive coverage and updates, Bolton’s own newspaper, the Enterprise, made no mention of this sad father-son exchange.

Related Stories

How Not to Rob a Bank: Shelburne’s First-ever Bank Robbery!

Mar 21, 2009 | | Historic HillsShelburne’s first-ever bank robbery began as a pretty scary affair, but in the hands of a bumbling stickup man it ended more like a gong show.

The Great Escaper

Mar 31, 2013 | | Historic HillsThe Orangeville Sun called him Robert the Bold. Local police called him ‘armed and dangerous.’ His neighbours called him ‘misunderstood.’ Bob Cook’s story fits all these descriptions – and then some.

Dealing with a Nightmare: The 1947 Palgrave Fire

Sep 13, 2012 | | Autumn 2012In the days before modern firefighting, nothing frightened a small community – or pulled it together more powerfully – than a major blaze. The 1947 Palgrave fire was one such case.

Sodom and Gomorrah? Melancthon Township?

Jun 20, 2008 | | Back IssuesScreaming headlines in Toronto newspapers turned an 1897 trial in Shelburne into a Canada-wide sensation, painting Melancthon as a hotbed of arson, fraud, perjury and intimidation.