A Day at the Caledon Equestrian Park

The intense bond between animal and human fuels two dedicated young equestrians at the top of their game at this exciting show jumping event.

Annika Vels’ head is backlit, high against a crisp, autumn sky, a disturbingly long way from the ground. Six feet tall herself, Annika sits atop Believe, a large (17.1 hands) chestnut mare with a naturally anxious disposition.

On this fine September Saturday afternoon, Annika and Believe are one of several horse and rider teams competing in the many divisions and classes of the 2018 Canadian Show Jumping Tournament CSI2* at Caledon Equestrian Park in Palgrave.

As Annika prepares to take her turn in the show ring, her focus is on the 78 seconds (or less) and the 12 metre-high jumps that lie ahead as she and Believe compete in the $10,000 Junior/Amateur Pan Am Challenge.

Annika’s mind is not on the in-progress status of her extracurricular college paper on hypothalamic amenorrhea. Nor on her busy four-day-a-week driving circuit – from the University of Guelph to the practice ring in Limehouse, near Georgetown, to the family farm in Erin, and the return to Guelph, where she studies biomedical science. Nor on her future as a naturopath to pay for her equestrian passion. Nor on any of the typical concerns and fancies of a bright 21-year-old with her future ahead of her.

Annika’s stomach hosts butterflies, but her head counts strides, processes her coach’s last-minute instructions, and runs through the imminent, almost imperceptible, choreography of legs, hands and body, honed over countless hours of practice. All of which she draws on to coax “B” – and herself – to perform their best.

Annika Vels shares a quiet moment with Believe in the practice ring. Photo by Rosemary Hasner / Black Dog Creative Arts.

Like Annika, Kilby Brunner Deforest is also competing in the tournament, though in different divisions. One can only imagine what is in the head of the petite, quiet 14-year-old who has just entered high school and is already in her 10th year of competition. At the very top of her game and leading provincial hunter-jumper rankings in her division, Kilby is focused over the neck of her pony jumper Beaverwood’s Halo (the first name after the family farm near Hillsburgh), and working hard in the warm-up ring before the competition. A competition Kilby intends, as she always does, to win.

Kilby’s head is up, her back straight, legs flexed, arms extended and down by Halo’s neck, hands loose, cheeks flushed, gaze swivelling to where she wants to go, as her pony swings, snorting, black tail flying, into a turn, brushing past the fence where onlookers lean in to watch and sense, in an instant, the controlled mass, speed, power. Of two athletes. And the fragility of one.

On Summer 2019 cover, Kilby Brunner Deforest with Beaverwood’s Halo. Photo by Rosemary Hasner / Black Dog Creative Arts.

Kilby is rarely afraid. “It depends on the horse. Nervous, maybe” is all she’ll allow, but the nerves don’t show in her self-possessed, serious demeanour. They do show in her mom, Kirsten Brunner, herself an accomplished rider and carriage driver whose focus is now on coaching and training, though she still competes occasionally. Kirsten is at every event – 17 shows or more in the 2018 season – and seems to be everywhere, hovering, watching, working – and when Kilby rides, taking deep breaths. “I worry,” she says. “That’s my child. On a thousand-pound horse, going 30 kilometres an hour.”

Annika and Kilby are just two of the many young Headwaters equestrians who put in countless hours looking after their horses’ needs and practising – after school, during holidays, in winter cold and summer heat – to develop their skills and test their limits in a sport that requires intense dedication and more than a little sacrifice.

Wearing a U2 T-shirt and dirty-boot civvies, Annika is relaxing briefly on a bench near a practice ring in the Limehouse barn she knows so well.

“Personally, I like horses more than competition,” she says. A late-afternoon breeze through the barn carries the smell of horse mash and manure, as well as the sound of neighs and the strains of the Ramones’ “I Wanna Be Sedated.” “This is my passion,” she adds, gesturing at the scene. “I made the commitment early on that I’m doing this for fun.”

Annika has no idea of her place in the rankings. (She sits mid-field.) A university undergrad’s schedule has seen her competitions – and point-gathering opportunities – reduced, and her looming post-grad courses in naturopathy will reduce them even more. And though she cares about succeeding, her dreams are realistic.

“I’m not going to ever not be an amateur,” she says. “I hope I can keep showing at the level I am at now, or less. It takes money, dedication and talent – a mix of all those – and luck, to really succeed.”

Money can’t trump talent, take the place of dedication or buy luck, but money, quite a lot of it, is needed to compete at the highest levels of equestrian sport.

The jumper Annika rides – registered name Believe in Liefhebber – cost as much as an SUV. She also rides a hunter named Leo, aka High Fidelity.

Stabling fees for horses competing at elite levels can run to $1,000 a month and more, per stall, including coaching but excluding routine vet and farrier bills. For more than routine, add a zero. Event fees can average about $500 for several events over a four-day competition, and then there’s the cost of trailering, daily care and coaching, normally about $50 a lesson but more for coaching over an entire event. (Coaches commonly work with several riders at a competition.)

A decent pair of riding boots can start at several hundred dollars – and go up from there. The same again for a workmanlike riding outfit. Tack and saddle? About the same as flights and a very nice weekend for two in Paris.

To offset these expenses, prize money is offered at the odd elite amateur event, but the pot is nothing grand. Kilby, tops in her class provincially, estimates she won $500 over the 2018 season, in addition to a roomful of ribbons and a few trophies. She’s more excited about a fancy jacket she’ll receive for topping the season-long one-metre pony jumper standings at Angelstone Tournaments near Erin – you can’t wear a trophy to school. Oh, and unlike an SUV, a horse’s value can substantially appreciate with good training and competitive success.

Mention “elitist” to an equestrian or their family and there is often an uncomfortable pause.

“It is a discussion that goes on,” says Annika, nodding goodbye to a fellow equestrian with whom she was discussing the costs of vet bills for a high-level competition horse. “It is very hard to make it in this sport without financial backing. It is the same with any sport at an elite level. There are student programs, grants, you can get rides by working at barns or teaching, but you can’t go out and buy a million-dollar horse, or even a forty-thousand-dollar horse. In that sense, yes, it is elitist. But you don’t have people looking down on other people. And just because you have money doesn’t mean you’re not putting in the time. Riders matter, but a five-figure horse is not going to be competitive against a six-figure horse.”

Bright sunshine, big sky, rolling rural backdrop, groomed grounds, mowed lots filled with pickups hitched to trailers, speeding golf carts, docile dogs, railbirds in quilted jackets, rumpled coaches, hovering moms, under-represented dads, kilometres of white railing festooned with ads for high-end anything, and expansive paddocks, schooling and show rings where erect, uniformed riders, mostly slim, mostly young, and overwhelmingly female, trot, canter, wheel and jump on gorgeous, glistening horses.

This could describe the scene at any equestrian venue, but at Caledon Equestrian Park on a late September Saturday, the scale is bigger – and the event is in our backyard.

“Horses love the place,” says CEP managing partner Craig Collins. “It is natural in its beauty. It has reliable footing. There is not a lot of noise and distractions. All this makes horses happy. Look at it! Do you enjoy being here? Horses do too.”

One thing that makes equestrian events unique, he explains, is the possibility of finding yourself standing beside a five-time Olympian. Across the park, events showcasing the highest level professional to the humblest of amateurs, aged seven to 70, take place at the same time. To employ a hockey analogy, every level from Tyke to NHL pro could be skating in the arena at the same time. “We are all attached by horse,” Craig reflects.

And, apparently, by a common esoteric language: oxers, fill, slice, warmbloods, pinned, under-saddle, hack, trips and rollbacks. Horse people know what these terms mean. They assume you do too.

Riders also compete in a bafflingly specific array of classes. Every level of skill, horse size, jump height, and competition for style or speed – or both – is on the program: Medium Pony Hunter, Pre Green Hunter, 2’9” Schooling Hunter, Baby Green Hunter, Adult Amateur 18–35 Hunter and so on. I just see horses. Jumping.

Annika Vels and Believe clear a jump in competition at Caledon Equestrian Park. Photo by Rosemary Hasner / Black Dog Creative Arts.

At the entrance to the park’s Grand Prix ring, the announcer broadcasts that Annika Vels, no. 300, is about to ride in the Junior/Amateur Pan Am Challenge (the event is open to both junior riders and those officially classified as amateurs).

Her name is literally in lights on a scoreboard at the far end of a vast, soft brown arena where a dozen jumps are meticulously arranged. But she hears and sees nothing. She’s in her head. If she is rattled by B’s two refusals (balks at a jump) and her elimination from the morning’s Table A Speed Junior/Amateur 1.0m Jumper event, it doesn’t show. Is she bummed out? “I’d say disappointed and a bit frustrated. It happens,” she says, her ready smile just a little less in evidence.

The buzzer sounds, and she and B are off. The smallish crowd perched on hillside stands is prepared to be hushed for 78 seconds (or less). Her coach yells, but probably more to himself. “Stay on your legs! Stay on your six, then go. GO!” And she does. As far as a green-and-white-striped triple combination jump on the arena’s far side.

Big, beautiful, bustling B suddenly stops in an inelegant head down, rump up, legs splayed slide-and-swerve. To gasps from the crowd, Annika is thrown up and over B’s shoulder, clattering into the rails with a crash. “Oh, B. Oh, B,” Annika’s coach sighs. “Zero for two.”

“Unfortunately …” The announcer intones the word all riders dread, and Annika, dusting herself off and with head held high, walks off, leading Believe and patting her neck. Annika will have a badly bruised hip and a hyperextended hand.

“Very uncharacteristic,” her coach keeps repeating. Neither he nor Annika knows what went wrong. Which troubles them. Usually one or both do. “The joys of riding a half-ton prey animal,” Annika laughs ruefully. “A lot of what they do is not to be naughty. It’s to react to danger. By flight. Don’t do a scary thing, run away. This is completely on me.”

Kilby Brunner Deforest on Halo makes a tight swing to the next jump at Caledon Equestrian Park. Photo by Rosemary Hasner / Black Dog Creative Arts.

It is completely on Kilby too. She and Beaverwood’s Halo are up against a now-familiar list of rivals on I Love Lucy, Moody Blue and Red On A Roll. She has beaten them before, mostly, at events all over southern Ontario, all spring and summer.

But it doesn’t happen this time. She places fifth in Pony Jumper Table A Speed. She, her coach and her mom are in earnest discussion, pantomiming – from a distance – moves that went wrong, while Halo stands by, impassive.

In the afternoon’s $500 Pony Jumper Classic, however, nothing goes wrong. Fourth after the first round, and with a time of 35.66 seconds to beat in the shorter, faster, jump-off round, Kilby is visibly, stunningly, quick and commanding. “Stretch! Bell! On it! ON it!” her coach yells and evidently she is, demolishing the opposition with a clean (no faults) winning time of 33.75 seconds.

Finished holding her breath, Kirsten laughs and gasps, “You’re killing me, you’re killing me!” while hugging both Halo and her daughter as a unit. Which they are. Kilby finally smiles. Beams, even – broadly.

If possible, her smile was even broader at last fall’s Royal Winter Fair in Toronto, the final equestrian event of the 2018 season. There, Kilby and Halo won both their classes and were crowned Royal All-Canadian Pony Jumper Junior Champions.

The smiles, stresses, beautiful surroundings, gorgeous horses, demanding courses and intense competition are already playing out again this year. Along with many other aspiring Headwaters horse and rider teams, Kilby and Halo and Annika and B are in the thick of things. Chasing perfection and victory – and doing their utmost to avoid those fifth-place finishes and announcers’ “unfortunatelys.”

Moment by moment with Annika Vels on the course at Caledon Equestrian Park

I’m not afraid. There definitely is a lot of adrenalin. Brutal in the gate. B is nervous. I don’t know if that is her nervousness, or mine she’s picking up on. She won’t stand still. She dances around. I let her do her own thing. I feel it but don’t respond to it. I’m going through my plan. I block everything out. I don’t hear the crowd. I never hear when they announce my name.

Walking the course beforehand, through every turn, through every approach, through every jump, my coach and I have gone through a plan for each specific two or three strides. Move off my inside leg here. Straighten her there. Keep her from shifting in or out. She’s mobile, moving her neck side to side, her shoulders and her barrel side to side, while going straight. Everything has to be straightened to keep momentum, to jump well. That’s hard for B. She likes to fall in through her turns. Put more inside leg on to counteract that. I’ve got to be really square on my turns.

I’m counting in my head, counting her strides: one–2–3–4, two–2–3–4. A large part of having a smooth, clean course is keeping a consistent rhythm.

There is a short distance between two jumps. Land the first, then collect her. She’s going to spook. Stay more leg and push her forward, so she doesn’t have as much time to react to the second.

All my thoughts are on something actionable, something that is going to help. She is balancing back and her hind end is really working. I’m conscious of that and influence that with body positioning.

B has overreacted? She’s trying to pull me through, go faster, which she likes to do. There is a sweet spot for takeoff. Watch or she’ll push past that, rushing, and she’s not going to jump clean. Sit up. Give on the inside rein. Turn my shoulder to get her flexed. There isn’t time to think. It’s automatic. Go with the horse. It is a mix of rocking horse and mechanical bull. You don’t want to get in a pulling battle with a thousand-pound horse. You’ve got to be smart about it.

I show my crop when she refuses. We have to come around and do it again. She’ll always go out left of a jump. I carry my crop left. I don’t hit her, just tap behind my left leg to remind her she has to move off my leg, right, going forward.

I’m talking to her. I make kissing noises to get more power. I shush to slow her if she’s spooking. I growl “Get!” to drive her. If she’s scared, I sing-song, “Heeeey . . . love. Eee zeeeee. Thaaaat’s. My. Girl.” Calm her.

I land the last jump and really push, push to finish.

I love this!

— as told to Anthony Jenkins

Some show jumping basics

First, the name of last September’s event at Caledon Equestrian Park: Canadian Show Jumping Tournament CSI2*. Though CSI may be familiar to many TV viewers as the title of a popular police-procedural series, in the equestrian world the initials have nothing to do with crime scene investigation. When it comes to horses, CSI refers to “concours de saut international,” or show jumping, and indicates the competition was approved by the sport’s Switzerland-based governing body, the International Federation for Equestrian Sports (aka FEI or Fédération Équestre Internationale).

The asterisk in CSI2* is actually a star that, when combined with the numeral 2, indicates two stars. They mean this particular tournament is at level 2 of a five-level system. Level 5 is the most competitive.

The levels govern the amount of prize money available, the height of the jumps and other variables. At the two-star level, for example, the maximum jump height is 1.45 metres, and horses usually start at this level when they are eight or nine years old. At the five-star level, horses are normally about 10 to 17 years old, which means they are physically mature, seasoned competitors capable of clearing jumps up to 1.6 metres. At national competitions, maximum jump height may be 1.7 metres.

Admission to the grounds at many Headwaters’ equestrian events is free. Food and refreshments are available, and venues such as the Caledon Equestrian Park and Angelstone Tournaments in Erin actively encourage spectators to bring a picnic lunch and enjoy a day in the sunshine.

Related Stories

Ballet on Horseback

Jun 17, 2014 | | LeisureCompetition is fierce for spots on the 2015 Pan Am dressage team – and four accomplished equestrians from the Headwaters region are in the thick of the race to represent Canada.

Cross Country at a Gallop

Sep 11, 2014 | | LeisureFor one day next summer, the eyes of the Americas will be on Mono’s Will O’Wind Farm, site of the cross-country phase of the Pan Am Games three-day event.

Ellen Cameron

Mar 31, 2013 | | Artist in ResidenceEllen travels with a camera as her constant companion, a tool that more readily allows her to record the subtleties of horses’ actions and interactions.

Going the Distance – On Horseback

Mar 31, 2013 | | Good SportEndurance riding is one of the fastest growing equine sports in the world.

High on Horses

Mar 31, 2013 | | LeisureAs Caledon prepares for the 2015 Pan Am Games, Headwaters Horse Country is saddling up for the ride of its life.

The Caledon Horse that Could

Sep 11, 2014 | | LeisureWith typical Canadian modesty, Rumble attributes the lion’s share of the credit for his achievement to his mount, a big-boned gelding named Cilroy.

David Peterson talks Pan Am

Mar 23, 2014 | | LeisureA long-time Caledon resident and avid horseman, David Peterson took time to speak with In The Hills about the impact the Games and the new world-class equestrian park will have on the area.

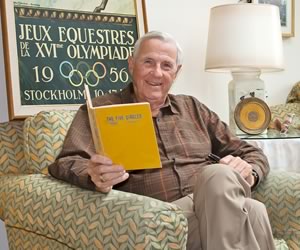

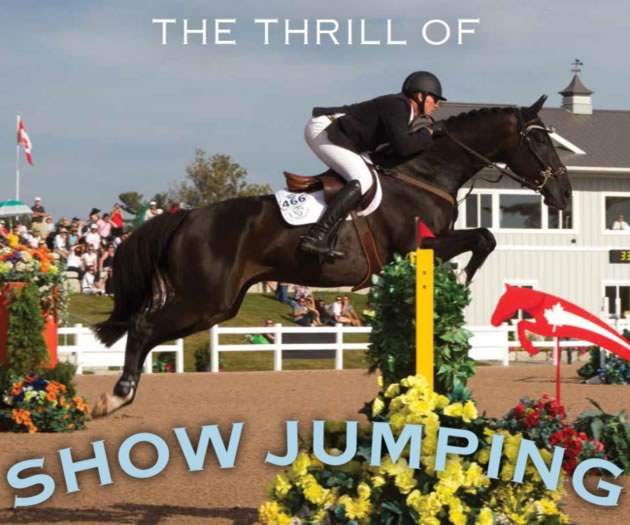

The Thrill of Show Jumping

Nov 17, 2014 | | LeisureLocal riders prepare to dazzle spectators with a breathtaking competition at the Pan Am Games.

Caledon’s Gypsy Connection

Sep 9, 2011 | | LeisureThe versatile, friendly and compact Vanners are often compared to golden retrievers for their companion-animal qualities.

Heavy Horses

Sep 11, 2014 | | LeisureHeart and muscle at the fall fair. Heavy horse pulls are crowd pleasers at Ontario’s fall fairs.