The Orange and the Green: A Legacy of Distrust

Animus between Protestants and Catholics brewed among early settlers in Headwaters.

For well over a century, daily life and local politics were dominated by the fiercely Protestant and intensely patriotic Orange Order. Roman Catholics, greatly outnumbered here, had to keep their heads down.

What was the problem?

A bit of oral history from the early days of Mono Mills might be apocryphal, but it suggests much. Around 1840 the community engaged a highly regarded teacher, a Catholic, for its tiny log school. Before the school year began, a member of the community’s Loyal Orange Lodge (L.O.L. 192) is alleged to have warned him “not to be teaching your Roman numerals,” but “to stick to good Protestant numbers.”

True or not, the story illustrates the religious distrust early settlers carried across the Atlantic and fostered here for generations. There was an inherent sense that the other side was just that – the other side. Catholics were suspected, not entirely without reason, of being loyal to the pope rather than to king and country (hence the term “papist,” a common Orange smear). On the other hand, Catholics felt shut out. They were a minority without influence and, not entirely without reason, believed themselves victims of bigotry.

The Orange/Green population ratio

Census data and the number of Orange Lodges show these hills were settled overwhelmingly by Protestants, many of whom were Orangemen. Peel County was noted by historian W. Perkins Bull to be “as full of Orangemen as an egg is full of meat,” an assessment echoed in measure, though certainly not in spirit, by the Roman Catholic Mirror which in 1843 described Bolton as “infested with Orange scoundrels.”

In Wellington, Simcoe and Dufferin, a count of lodges reveals impressive numbers. In 1905, for example, members of no fewer than 19 lodges came to Grand Valley from just a carriage ride away when L.O.L. 256 hosted Orangemen’s Day, the annual 12th of July celebration. In 1931, crowds on Orangeville’s main street cheered on 53 lodges in the Glorious Twelfth parade, and in 1962 there were 91 lodges in the march.

Catholics living here could join Corpus Christi parades or Rogation Day processions but had to travel to Toronto or Guelph for that, or sometimes Adjala Township and in later years Melancthon Township. Until the later 1900s there was nothing close to an Orange/Green balance. Catholics were too few in number to mount any celebration as impressive as that of their Protestant neighbours.

Parties and patronage

Orangemen’s Day was both party and annual general meeting. It was the biggest event of the year in every community, and if Catholics showed up, it was rarely by invitation (and never to official dinners and speeches).

Huge crowds filled every community on Orangemen’s Day. In Caledon East, c.1900, the Ontario Hotel had to install extra balcony supports for this group photo. Photo courtesy Doris Porter.

Local lodges were social clubs and the local Orange Hall was the ultimate site for making political and patronage connections. In January 1881, following the first county council meeting in brand new Dufferin County, where nearly every councillor was a past or present officer of an Orange Lodge, local papers reported uncritically that the majority of paid municipal appointments went to Orangemen. This kind of patronage was common not just in these hills but around the province, an irritant remembered long after the Orange Order’s influence had declined.

External pressures

Despite a range of annoyances, the two sides got along remarkably well in their own neighbourhoods. Most often it was outside forces that stirred the pot. In 1923, for example, in response to the idea that “O Canada” be our national anthem, The Sentinel, an official organ of the Order, fired up its well-oiled, anti-Quebec rhetoric, calling the anthem “a French Canadian racial hymn,” and harrumphing that “until this Dominion becomes a French Canadian republic, our anthem shall be ‘God Save the King.’” The Shelburne Free Press and Economist dutifully reprinted the editorial, presumably assuming it reflected local majority sentiment.

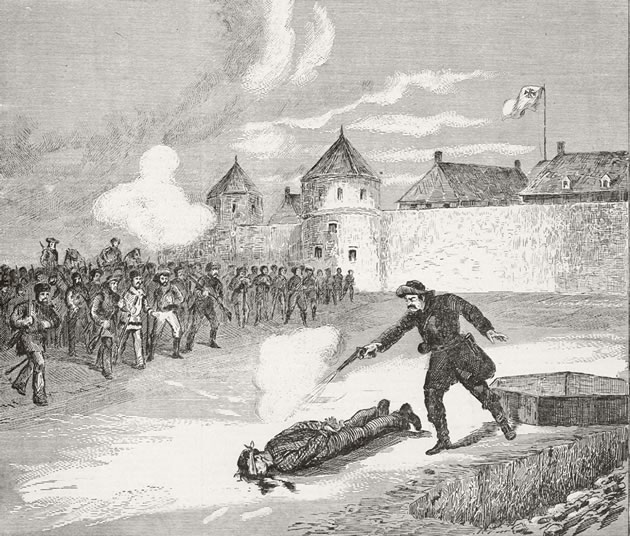

The anti-Catholic rhetoric was exponentially exacerbated in the latter half of the 1800s by the activities of the Fenian Brotherhood, a U.S.-based society seeking Irish independence from Britain. The brotherhood’s idea was to conquer Canada to use it as a bargaining chip in their struggle. Through the 1860s and ’70s the Fenians attempted to invade Canada several times, doing more to fire up Orangemen than even Pope Pius IX, whose extremely conservative pronouncements were often used against local Catholics.

Inflated tales of violence

Although rumours of an imminent Fenian attack were occasionally serious enough to bring militia to the streets and sideroads here, the history of violence between Orange and Green in these hills is more legendary than factual. A popular tale, for example, describes Ballycroy (mostly Green) versus Palgrave (mostly Orange). In one oft-cited account, members of L.O.L. 185 in Ballycroy were frequently pummelled as they walked past a “Catholic tavern” en route to their meeting hall. Reputedly, they were avenged in turn by a Captain Wolfe from Palgrave whose horse kicked down the door of the tavern. Since the same captain’s horse seems to have taken down various tavern doors in Centreville and other places, the story, like many others, remains dubious.

Certainly some brawls did occur, especially on the Fourth Line of Albion Township between the Catholic-Irish of Centreville (aka “Helltown”) and the Protestant-British of neighbouring Lockton, but even these tussles tended to be isolated affairs that almost always blew up in a tavern. Most verifiable stories about Orange and Green show that while the distrust was real, people on both sides preferred simply to get along.

Ultimately friends … just not pals

Among the striking stories of co-operation is that of Lodge brothers in Caledon’s Silver Creek who, in 1886, carted bricks from Orangeville to help the Catholic parish rebuild its St. Cornelius church in the village. Their gesture not only contradicts the purported animosity but shows how the pioneer ethic of help-your-neighbour inspired both sides to see beyond the religious divide.

Another such tale comes from the early history of the Sheldon mill on the Mono-Adjala Townline. In the early 1800s the townline became a mutually agreed border. Catholics settled to the east in Adjala, Protestants to the west in Mono, and new settlers were advised of the practice. But in the 1840s, when the area’s first grist mill was built at Sheldon Creek on the townline, farmers from both sides needed it and, given the slow milling practices of the day, Orange and Green literally had to lie down together while they waited, usually overnight, for their grain to be ground.

In pioneer society the immediate demands of daily living were far more compelling than abstract principles. Though there was time and opportunity, there were no recorded fights at the Sheldon mill. And there were no fights at the McLaughlin brothers’ grist mill in Mono Mills either. The McLaughlins were Catholics who, in addition to their mill, opened a store that housed the first village post office (the postmaster was a Protestant minister).

The legacy in perspective

Such day-to-day co-operation doesn’t mean history has overstated the animus that once prevailed here. It was genuine and pervasive, and it took several generations to fade away. Still, compared to the violence and intractable disagreements that religious differences have roused around the world for centuries, the bigotry that rose, thrived and diminished over 150 years in these hills was relatively mild.

For example, however suspicious the members of L.O.L. 192 were of the Catholic teacher in Mono Mills – and his agreement to teach only Protestant numbers – the Orangemen are alleged to have contented themselves with eavesdropping at the school window to ensure he didn’t slip other papist doctrine into his lessons.

Caledon writer Ken Weber is the author the internationally best-selling Five-Minute Mystery series. This is his 100th Historic Hills column in this magazine since his first one in 1996.

More Info

The Orange Order and the Glorious Twelfth

On July 12, 1690, Protestant succession to the British throne was assured when The Netherlands’ Prince of Orange defeated his Catholic father-in-law, James II of England, at the Battle of the Boyne in Ireland. Both the battle and its date are ritual touchstones of the Orange Order, a fraternal society founded in Ulster in 1795 to support Protestantism and the British Crown. Canada’s Grand Orange Lodge was established in the 1820s and over the next 100 years grew to a position of power and political influence. Though still functioning today, it is a shadow of its former self.

Must have been a party!

James Foley, Jr., editor of the Orangeville Sun and an Irish Catholic, dutifully reported Orange Lodge activities with respect and considerable detail. Still, it’s tempting to believe that in writing his account of the Glorious Twelfth in 1909, he may have indulged in at least a small smirk. More than 200 Lodge brothers from Dufferin County went to Brampton for the big day and celebrated with such enthusiasm they missed the last train home and had to spend the night in the Brampton station.

Related Stories

Prohibition pits “wet” vs “dry”

Jun 15, 2010 | | Historic HillsIn the 1880s, prohibitionists took the fight for liquor control to the voting booths of the nation. In the hills, choosing “wet” or “dry” became such a hot button that neighbours and whole communities were pulled in different directions.

The Rebellion of 1837: Not Just Montgomery’s Tavern

Nov 17, 2012 | | Historic HillsThe rebellion in Upper Canada finally got British authorities to look into what was upsetting the colonies.

The Red River Rebellion: The Hills Get Indignant!

Nov 25, 2015 | | Historic HillsThere was the button that always cranked these hills beyond reason – the hint of anything Fenian.

The Party that Grew: Drummers’ Snack

Mar 23, 2008 | | Historic Hills“We did not see a drunken man on the grounds,” observed the Advocate (although the paper did wonder who rang the park bell at 6 a.m. on Saturday morning).

Bringing ‘The Word’ to the Wilderness

Sep 9, 2011 | | Historic HillsOf the worshippers in Mono Mills he complained, “When they should rise, they sit; when they should sit, they continue standing.”

Memoirs of a Caledon Pioneer

Nov 15, 2007 | | Historic HillsAfter the ox cart driver bid farewell and left us, and I began to clear away the snow where we were to lay our bed.

No Easy Way to the Promised Land

Jun 20, 2019 | | Historic HillsGetting to Upper Canada took determination – and good luck.

Excellent history and research. In my own family research I found a 3rd great uncle, David Brethour, whose family came from Ireland, joined the Orange Lodge in Peel in 1852. Recently, I have published a book to assist others in searching for Orange Lodge members in Canada. It is called “1892” and available on Amazon.

Brian McConnell from Nova Scotia, Canada on Mar 16, 2023 at 6:12 am |