Prohibition pits “wet” vs “dry”

In the 1880s, prohibitionists took the fight for liquor control to the voting booths of the nation. In the hills, choosing “wet” or “dry” became such a hot button that neighbours and whole communities were pulled in different directions.

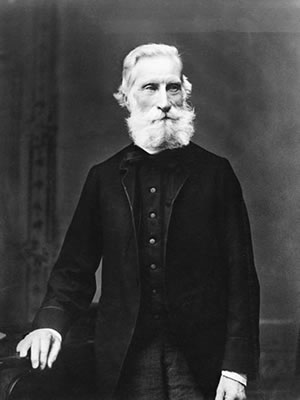

The temperance movement was but a smouldering ember in the nineteenth century until a piece of legislation in February, 1878 fanned it into a raging fire. The Scott Act, named for the Liberal MP who pushed it through Parliament just months before one of the country’s best known imbibers, Sir John A. Macdonald, returned to power, established the principle of “local option.”

If just 25 per cent of the electors in a city or county petitioned for a vote to prohibit the sale of alcohol, then a vote had to be held and the result would be binding on the entire city or the entire county.

A Prohibitionist’s Dream

The Scott Act was a plum for the “dries,” the supporters of temperance and prohibition. For one thing, it overrode existing – and very confusing – legislation, thereby closing loop-holes for the “wets.”

Early in 1884, for example, Shelburne hotel owners were told the McCarthy Act meant only three of them could get a liquor licence, so the owners reapplied under the Crooks Act and got four with a promise of more! That kind of end run stopped with the Scott Act.

Even more attractive for the “dries,” the Act mandated that a simple majority, 50 per cent plus one, was sufficient for victory. In Dufferin, that meant that the Shelburne vote, guaranteed to be a wet “No!” could be more than offset by a dry “Yes!” from Orangeville where the population was larger and prohibitionists were powerful.

The most delicious plum of all was that if a city or county voted “dry” as its local option, the legal sale of alcohol would be eliminated completely. Hitherto, both provincial and federal laws had merely fiddled with the controls, but now things were different, so here in the hills the prohibitionists got right to work.

Into the Fray

Although the Act became law in 1878, legal rulings such as the one that decreed towns and townships were subordinate to counties and could not decide their own local option, delayed voting in most of Ontario until 1884. Both “wets” and “dries,” especially the latter, used the time to crank up their campaigns.

Local clergy thundered from the pulpit – no surprise there – but in Dufferin the newly constituted Salvation Army (locally known as the “Lord’s Army,” not always with respect) took it a step further. Members would march up Broadway and kneel in the street before the Queen’s Hotel, conveniently located within sight and hearing of five more hotels, to sing and pray for the patrons and their servers inside.

Other groups were slightly more sophisticated in their approach, although hardly subtle. The Royal Templars of Temperance, for example, ran regular performances of the way-over-the-top drama, “Ten Nights in a Bar Room,” in Orangeville, Alton, Erin, Bolton and Caledon East. As well, touring temperance speakers were invited to camp-meeting rallies in ham–lets like Camilla and Mono Mills.

Letters to the editor were a key element, with both sides appealing to the Old Testament. “Prohibition was the first law promulgated in the Garden of Eden!” Mr. J. Snell advised Bolton readers, prompting Joseph Vogan of Caledon to respond that the first thing Noah did after the waters receded was plant a vineyard and make wine.

Others placed emphasis on the New Testament, with several anonymous writers from Peel citing Jesus turning water into wine. Responding to this example may have over-stimulated a popular temperance orator, Susannah Pech, who is alleged to have told an audience at Perdue Hall in Bolton that if Jesus made wine we can use to get drunk, perhaps we don’t need him as a saviour! (There is no record of Ms. Pech ever speaking in Bolton again.)

Interestingly, the editorial position of local papers tended to be anti-dry. While that was somewhat expected of the Brampton Conservator and the Shelburne Economist, it was a surprising position for James Foley of the Orangeville Sun.

Foley was a temperance advocate, but argued that voting Dufferin “dry” could seriously endanger the livelihood of the county’s farmers because of the negative impact on sales of barley. (Foley’s argument was prescient; after many parts of Canada voted for prohibition in the 1880s, the price of barley – essential to distillers – dropped significantly.) Perhaps most interesting of all was the relative silence of hotel owners and distillers on the issue. They had the most to lose, but throughout the grand de-bate their collective profile remained remarkably low.

Applying the ‘X’

Until the 1880s, voting days in Canada were often marked by brawls, but the same government that passed the Scott Act (the Liberals under Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie) had also brought in the secret ballot, so on local option voting day (Oct. 23, 1884 in Peel; eight days later in Dufferin), the voters were safe. Not so for the ballot boxes, at least in Dufferin. In Mulmur Township, the boxes at Mansfield and Banda disappeared after the polls closed; likewise at Riverview in Melancthon, Coleridge in Amaranth and Ewing’s in Mono.

Needless to say, when the boxes were recovered, all contained a majority for the “dries.” Not that it mattered. Every poll in Dufferin County with the single exception of Shelburne, had voted “dry.” Peel, however, went “wet,” and in a big way. Caledon Township and the Village of Bolton were the lone polls heavily favouring prohibition. The others reflected a different view. In Albion Township, for example, for each voter choosing “dry,” there were twelve who chose “wet.”

The Outcome?

For the very first time on a major legal and lifestyle issue, these hills were split. Peel, in the opinion of the most strident prohibitionists, had sold its soul to the devil. Yet as a “wet municipality,” the county experienced comparatively little difficulty with alcohol issues.

In Dufferin, things were different. James Foley’s prediction following the Dufferin vote, that a hitherto well-managed commerce by hotel keepers would now be “driven into low groggeries and vile haunts,” was reinforced by the statement of a travelling sales-man only a few years later: that one had but to name a concession road in Dufferin County and, in turn, he could name its illegal still. It was a difference in these hills that would prevail for years to come.

It Seemed Like a Good Idea at the Time

As a cure for what temperance advocates saw as a social curse, the Scott Act – its actual title is the Canada Temperance Act – was a total failure. Through the mid-1880s, when Peel and Dufferin were taking their separate paths, most Ontario counties, indeed much of Canada (except Quebec) voted to go “dry.”

There were two immediate outcomes. One was the growth of a vast, illegal liquor trade; the other was violence directed at Scott Act enforcers who, in Dufferin and several other counties, faced gunfire and even dynamite.

Even relatively peaceful enforcement did not always succeed. At magistrate’s court in Wellington, for example, in August 1886, thirteen separate charges were heard, most of which were dismissed when witnesses suddenly failed to recall seeing liquor being served during the incidents in question.

Fortunately, the Scott Act had an escape clause in that a vote for “dry” had to be revisited within three years. By 1888, every county in Ontario had voted to abandon the local option.

Ontario Turns Off the Tap Again

The Ontario Temperance Act was passed in 1916 under Conservative premier William Hearst, a dedicated teetotaller. By 1917 every other province followed suit (except Quebec). Once again, a thriving bootleg trade arose, even more successful this time because of the many cross-border customers subject to rigorous prohibition laws in the United States.

The Ontario Act was repealed in 1927, but the illegal border trade carried on until 1933 when prohibition came to an end south of the border. Various forms of local option in Ontario continued, however. Orangeville remained famously “dry” for years. And as recently as 1966, Caledon Township voted down the sale of beer in licensed establishments where women were permitted.