August 1914: The First Goodbyes

As early as August 7, the word went out to militia units across the country: Enlist as many volunteers as possible.

For a hundred years people from Europe had flowed into these hills to begin a new life. In August 1914, the tide reversed. Suddenly families were bidding anxious goodbyes to loved ones going the other way.

When the unbelievable happened in Europe in the first week of August 1914 – when all the diplomacy failed and the complicated treaties kicked in, dragging the entire continent into war – most people here in these hills were only too glad to be living in a rather remote corner of the British Empire. They were justified in feeling somewhat detached. Not only was the conflict far away, but the warring European countries also had professional, well-trained armies to do the fighting. Besides, experts were predicting the whole thing would be over by Christmas.

Soldiers and their loved ones say goodbye at the Shelburne railway station, 1914. Photo Courtesy Dufferin County Museum And Archives P-0009.

But then came the call to arms

Those comforting thoughts lasted mere days. At the time, Britain still controlled Canadian foreign policy, and deep down everyone knew that when Britain was at war, Canada was at war.

As early as August 7, the word went out to militia units across the country: Enlist as many volunteers as possible. Among the units receiving the order was the 36th Peel Regiment, which included men from companies based in Shelburne, Orangeville, Mono Road, Brampton and Port Credit.

With no idea what they were in for, these early recruits were eager to get into the fight. On August 13, the Shelburne Free Press quoted Major Frederick John Hamilton, second-in-command of the 36th Peel: “We are ready to move off [to Europe] inside of 24 hours.”

A week later, local papers told readers that a fleet of liners was massing at Quebec City to carry Canadian soldiers across the Atlantic. Thus, even before the month ended, it had become obvious: the war might be “over there,” but Canada – and the 36th Peel – was going to be in the thick of it.

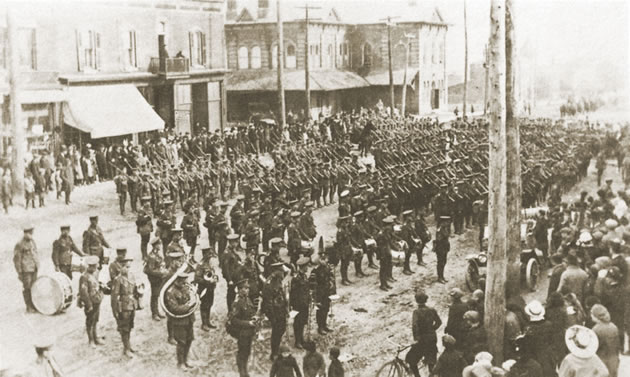

World War I: The 164th Battalion lines up on Broadway, Orangeville. From Into The High County by Adelaide Leitch.

How bad will it be?

No one was using the term “world war” in August 1914, but it was clear the Canadian government was taking matters seriously. In a speech on August 19, Prime Minister Robert Borden pledged that Canada would stand “shoulder to shoulder with Britain and the other British dominions in this quarrel.”

For the first time since the Fenian raids of the previous century, a full-time guard unit was placed at the Welland Canal. Heavy guns were mounted around the ports of Vancouver and Halifax. Newspapers ran comparison columns in the manner of sports news, totting up the potential power in the type and number of armaments each European country had in its arsenal.

Even so, for the people of these hills, much of this reporting had little immediate consequence. The fact that 331 submarines were being readied for action in the Atlantic did not count for much along the concession roads of Peel and Dufferin. What did catch the eye of local farmers, however, were ads telling them the army was looking to buy horses. Out on the concessions, that was real. Even more real were the orders from Ottawa calling on the recruits to assemble at Valcartier, Quebec, the hastily thrown-together camp that would become the training ground for the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Things were happening fast.

With cheers and tears, the first goodbyes

As August 1914 unfolded, many a tearful embrace was seen at railway stations in Shelburne, Orangeville and Bolton, as well as at flag stops such as Crombie, as the recruits from Peel and Dufferin left to assemble at Brampton. There on August 17 the soldiers prepared to leave for Toronto on the morning train and the impact of their departure gathered steam.

With no official announcement, and literally just an hour’s notice that the men were leaving, shops closed their doors and factory workers left their machines. By the time the train pulled out, an impromptu parade had marched down Main Street led by the Brampton Citizens’ Band carrying a huge Union Jack, and more than 1,500 people had crowded onto the station platform to cheer and bid goodbye.

On August 20, 228 officers and men of the 36th Peel left Toronto for Valcartier, their last stop on Canadian soil before heading across the Atlantic to Europe. Another large crowd gathered at the Canadian Northern depot on Cherry Street, where they stood in pouring rain to say their farewells. Perhaps it was the weather, or maybe it was that there was now no turning back, but according to the Toronto Daily Star, the tears on that morning far outnumbered the cheers.

As 32,000 early recruits poured into Valcartier from across the country, conditions were chaotic. The former farm was infested with snakes, equipment and khaki uniforms were in short supply. As one officer of the 36th Peel noted, “order, counter-order, disorder” reigned.

To add to the confusion, many 36th Peel recruits were shuffled into and out of various newly formed battalions until finally four officers and 112 other ranks – about half the Dufferin and Peel men who had signed up in the early days – became F Company of the 4th Battalion and the rest were assigned to a variety of other units.

When the fighting finally ended in 1918, the number of Canadians who served in what came to be called the Great War had grown to well over 600,000. Close to 1 in 10 died and 172,000 were wounded.

In August 1914, among the first of many thousands, men of the 36th Peel march in Toronto to the train that will take them to Quebec to prepare for duty overseas. Peel Art Gallery, Museum and Archives.

The next goodbyes

The 4th Battalion embarked for England in September 1914, and for nearly four months drilled in the mud of England’s Salisbury Plain before heading to France in early February 1915. After another month of training, the Canadians were sent to what was by then called the Western Front in early March. If there were any doubts that the boys from the hills were truly in for it, they were completely wiped away by a letter to the Orangeville Sun, published May 27, 1915.

What Sergeant John Mills told the Sun must have somehow escaped the censors, for his letter provided excruciating details of what he called a “slaughter” with 700 of the battalion killed, wounded or missing. Mills was describing what is now called the Second Battle of Ypres in Belgium, a heavy assault by the German forces that included the use of gas. Even so, the Canadians, including the 4th Battalion, proved their mettle, holding the line at a terrible cost.

Shortly after that disturbing letter, the Shelburne Economist reported the 36th Peel had been ordered to recruit 150 additional officers and men. It surely meant the next goodbyes were going to be more anxious than ever.

The 36th Peel went through several name changes before emerging as the Lorne Scots of today. This fall marks the sesquicentennial of the regiment and, in conjunction with the Lorne Scots Museum, Peel Art Gallery & Museum is hosting an exhibition called Service & Remembrance: 150 Years of the Lorne Scots. See details in Must Do.

A different kind of recruit

A century ago, it wasn’t uncommon to see groups of men from these hills boarding trains every August. In 1914, the annual August harvest excursion to the Canadian West drew hundreds seeking to earn extra cash. Whether the trip was for profit or adventure is debatable. A CPR excursion ticket, round trip to Winnipeg, cost $18 and the average net pay for a month was about $40, including free meals and lodgings, which were rarely praised. In 1914, the pay of an army private was $1.10 a day, if he went overseas. In World War I, men from these hills went west as well as to war, for the wheat fields of the Prairies fed Europe, and workers were urgently needed to bring in the harvest.

The first to go

When the call for 25,000 Canadian volunteers went out in August 1914, it specified that men of appropriate physical condition between the ages of 18 and 45 would be preferred. Within that age group, unmarried men would be chosen first, then married men without families, then married men with families. The first group of 36th Peel recruits included only one married man. According to the Brampton Conservator, a recruit’s “ability to shoot straight” was also a determining factor.

A century of controversy

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the prolonged, brutal and highly controversial battle of the Somme. By this time in 1916 – mid-September – fighting along the Somme River in northern France had been raging for two and a half months.

A year into the war, the men of the 36th Peel who had survived the early fighting, whether in the 4th Battalion or other units, were in the thick of the carnage along the Somme. And carnage it was. By the time the offensive ended in a stalemate in mid-November, both the Allies and the Germans had suffered hundreds of thousands of casualties. Among the 620,000 Allied casualties were more than 24,000 Canadians. Given the enormous cost of this battle, historians have debated the wisdom of the Allied commanders’ approach and tactics ever since.

Though the 36th Peel no longer exists as such, the regiment’s legacy is perpetuated today in the Lorne Scots (Peel, Dufferin and Halton Regiment), a reserve unit headquartered in Brampton. Because members of the 36th Peel were so widely dispersed during World War I, their battle honours are held by many regiments, including the Lorne Scots. Among those honours are Ypres and the Somme, as well as many other famous World War I battles.