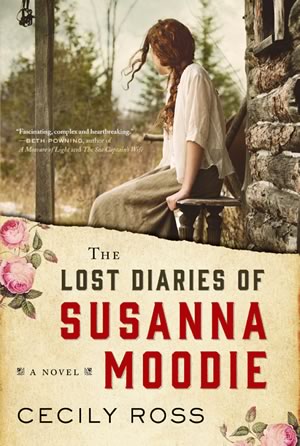

The Lost Diaries of Susanna Moodie

Author and In The Hills contributor Cecily Ross’s new literary novel colours in the outlines of iconic Canadian pioneer woman Susanna Moodie.

With The Lost Dairies of Susanna Moodie, Creemore author Cecily Ross adds a new perspective to the imaginative responses to Canada’s most famous literary pioneer. By birth Susanna was a Strickland from Suffolk, England. She was the youngest of six sisters, five of whom were writers, as was her younger brother Sam. In 1832 she reluctantly immigrated to Canada with her husband John Dunbar Moodie and endured seven harrowing years with her growing family in the bush north of what is now Lakefield, Ontario.

Moodie struggled and she endured, but she pined for the world she had lost. Finally, in 1852 she wrote very personally about her experiences, entitling her autobiographical sketches Roughing It in the Bush. Until her death in 1885 she considered herself “a [Canadian] daughter by adoption.”

Author Cecily Ross offers a fresh, accessible and at times wrenchingly emotional version of Canadian literary icon Susanne Moodie. Photo by Rosemary Hasner / Black Dog Creative Arts.

I encountered Susanna Moodie when I was assigned to teach Roughing It in the Bush at Trent University in 1972. I was relatively new to teaching Canadian Literature and was learning about it as quickly as I could. I did know “the bush” in question was just north of Peterborough and that Margaret Atwood had written a book of poems called The Journals of Susanna Moodie in 1970. I found Atwood’s interpretation stimulating and disturbing, magnifying Moodie in vivid and startling ways, but depriving her of her personal voice and her sense of humour.

Flash forward to 1978. As a project for my first sabbatical, I began to explore what was reliable and worth knowing in the welter of early historical and critical accounts of the writings of Moodie and her sister Catharine Parr Traill (Kate to her family). The latter’s book, The Backwoods of Canada (1836), was almost as well-known as her sister’s, and some critics viewed it as more admirable.

I soon became absorbed in the research and, with colleagues from two other universities, began a search that led to collections of the sisters’ letters, scholarly editions of their books, critical essays and biographies. One of my delights was to provide information to Charlotte Gray as she researched her double biography Sisters in the Wilderness (1999).

There are two paths that can be followed regarding the Strickland sisters. Mine is academic, historical and critical. The other is creative and imaginative. Indeed, the creative path was trod even before Atwood’s poems. Robertson Davies wrote a play involving both Moodie and Traill. Entitled At My Heart’s Core (1950), it was set in Peterborough. Notably, Davies disliked Moodie and made her a rather disagreeable character in his drama. Few since have been as negative about her.

Today Susanna Moodie continues to fascinate readers and creative writers alike. She has proved to be both a treasure trove and a foremother for numerous Canadian writers. I count among them Carol Shields (Small Ceremonies, 1976), Julie Johnston (Susanna’s Quill, 2004), Timothy Findley (Headhunter, 1993) and filmmaker Patrick Crowe who, with Carol Shields, wrote the script for a graphic novel version of Roughing it in the Bush (2016).

Ross’s Lost Diaries adds impressively to that roster. I found it a compelling read. In it the Susanna Moodie I have come to know and admire is presented with sympathy, feeling and, though fictionalized, close attention to historical accuracy.

The author’s uncanny ability to channel Moodie comes in part from her own life experience. Like her subject, she is an experienced writer and editor, including contributions to this magazine. And she likewise comes from a writerly family (including her sister, In The Hills columnist Nicola Ross). She even has a cheerful, scientifically-inclined sister named Kate.

But Ross’s inspiration runs deeper than that. As a young mother, she lived immediately across from the Moodies’ first homestead in the countryside near Port Hope. She and her two daughters explored the site with imaginations set afire by their reading of Moodie’s tales of hardship and perseverance. Indeed, one could argue that as a novelist, Ross succeeds in dramatizing her story more effectively than Moodie herself was able to do in her famous book – writing as she was primarily for a staid Victorian readership back home in England.

There is no extant evidence that Moodie kept her own diary, but we do know her sister Catharine Parr Traill did. So the probability of “lost diaries” does exist. Following that lead, Ross escapes the genteel writing traps that constrained Moodie. The Lost Diaries of Susanna Moodie offers a fresh, accessible and at times wrenchingly emotional version of Canada’s best known pioneer writer and literary icon.

Excerpt from The Lost Diaries of Susanna Moodie

Excerpt from The Lost Diaries of Susanna Moodie by Cecily Ross ©2017. HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved.

After leaving Reydon Hall, her idyllic childhood home in Suffolk, and making the crossing to Canada in 1832, Susanna and John Moodie first settled in what was little more than a cowshed near Port Hope. Although they eventually moved to a modest house, the inexperienced farmers struggled to make ends meet. Susanna’s sister Kate (Catharine Parr Traill) and younger brother Sam had moved north to Douro Township in the backwoods. Enticed by the proximity to her two beloved siblings and the prospect of a fresh start, the Moodies and their two small daughters soon followed. In this excerpt Susanna recounts their journey and reunion.

February 17, 1834 (Westove, Lake Katchewanooka)

It is two weeks since I was reunited with my dear sister and long-lost brother, and sitting here now in front of the Traills’ wood stove while the winter winds buffet their modest log home, I already feel transformed in some unknowable way – no longer Susanna of the Suffolk heath and broads, but a changeling I am only barely coming to know. The circumstance of my rebirth comes to me as if in a dream: Our journey north from Hamilton Township. The sledge poised on the crest of a fallen tree, the horses struggling to haul it down the other side, the driver calling out, urging them on, his whip cracking, and then slowly, slowly, the whole conveyance teetering and finally crashing onto its side, our worldly goods spilling out, pots and blankets, axes, barrels, tools, the paraphernalia of a settler’s existence. And then the box of china – the blue-and-gold Coalport tea set Mama gave me – tumbling through the air, emblems from another life, smashing into a thousand pieces against the immoveable frozen shield. I fell down weeping, ridiculous with exhaustion and rigid with cold after an eleven-hour bone-shattering journey from Hamilton Township (our drivers having decided to push through and make the two-day trip to Douro in just one day).

Shards of porcelain glinting in the moonlight – remnants of my old life. To think I carried that tea set across the vast ocean and over mud roads and forest tracks, that I stored the cups and saucers with such tenderness at the bottom of the flour bin all through our first winter huddled together in a lowly cattle shed. On the worst days, when the wind coming through the walls was like knives, and the sour smell of tallow and woodsmoke turned my stomach, and I thought I would give my first-born for a cup of real coffee, in tears, I would take the box out, dust off the gold crest embossed on its mahogany surface and press the cool, civilized sheen of a cup or a saucer to my rough, wet cheeks and think of Reydon Hall, of the lilacs in bloom, of the carpet of rosemary spreading between the flagstones in the back garden, of Sarah playing Mozart on the pianoforte. Foolish, foolish woman.

On my hands and knees in the snow, I began frantically gathering up the bits of crockery, making little piles, fitting this splinter onto that fragment like pieces in an unsolvable puzzle. But everything was destroyed, all except the sugar bowl’s delicate lid with its gold-leaf handle, which I slipped into my pocket, a grim reminder.

Moodie pulled me to my feet. “Praise God, no one is hurt and the horses have been spared. Leave the china, Susanna. It doesn’t matter.” He helped me back to the other sledge, where the babies slept on in blissful oblivion. And I knew he was right. None of it mattered. The past. England. The woman I used to be.

We were within sight of Sam’s house when the carnage occurred. And the only thing that kept me from coming completely apart was the figure of my brother emerging from the shadows like a knight errant. I didn’t realize who he was at first and watched, numb and emptied out, as this bearded, barrel-chested man clad in a great fur coat took charge of the situation, calming the horses and directing Moodie and the drivers in their so-far-fruitless efforts to right the overturned sledge. But when I heard his voice, resonant with the scenes of my childhood, though deeper now and suffused with self-assurance, I knew it was him, and the broken china was forgotten. I climbed down onto the moonlit snow and went to greet him, weak with joy at the sight of my own flesh and blood at last. But Sam, dear no-nonsense Sam, with a brusqueness that makes me gasp to think of it now, merely took me by the shoulders and ordered me back into the sledge.

“We’re not there yet,” he announced. “You’ll be staying at Westove. Kate and Mr. Traill are expecting you.”

“But Sam,” I protested, as horrified that he had barely acknowledged me as I was that our ordeal was not yet over. “Sam, it’s me, Susie.”

He paused and flashed me a broad grin, aware perhaps that he should make more of our long-anticipated reunion. “Sister. You look well,” he said. His smile faded imperceptibly. “Different. But good. Good.” And then he was off, grabbing one of the horses by its bridle and heading into the trees. A man of action, not words. I had forgotten.

In the end, it was only ten minutes more until I was transported into the consoling circle of my dear sister’s arms. I can barely recall it, but Moodie tells me I half swooned and had to be almost carried into the smoky comfort of Kate’s little home, into the halo of her embrace. After an orgy of greetings and tears, once our wet clothing had been removed and our stomachs filled with a sweet and spicy stew – “Venison,” said my sister, “from my Indian friends, and juniper berries” – we lapsed into a formidable silence. Too much has happened. Too much to say. Her little son, James, awakened by the invasion of noisy visitors, sat on his father’s lap and regarded us with solemn curiosity. Addie, almost the same age as her cousin, brazenly reflected his gaze from the safety of Moodie’s arms. Kate, who has not seen her namesake since she was a tiny baby, turned her full attention on my shy two-year-old, coaxing her onto her lap with promises of songs and stories. Sam left the cabin, returning with an armful of wood for the blazing hearth. My little brother Sam. Who is this sturdy pioneer? What do you say after so long?

But Kate, my sister Kate, is hardly changed – thinner, and if anything prettier, but still Kate. And as I watched her putting out bowls and pouring hot coffee, laughing like the young girl she once was, her cheeks red from the warmth in the room, the incredible swirling warmth, then all the months and miles, all the oceans and rivers and lakes that have been between us, melted away. We were together again.

Miniature portrait of Susanna, 1820s. National Library of Canada 15557.

I pulled my sister’s shawl closer. It smelled of chamomile and woodsmoke. While the men stood by the fire and talked of land prices and the weather, and Kate amused her niece, I looked around the cabin, at the walls hung with maps and hunting prints, at the green-and-white curtains covering the tiny windows, a rug woven in zigzags of colour covering the rough planks of the floor, tidy rows of jars and tins lining the pantry shelves, bouquets of dried weeds and flowers strung from the rafters, baskets decorated with dyed quills and coloured beads, a row of moccasins by the door, a quilt, both simple and intricate, draped over the back of a pine settee. I surveyed all this and considered Kate, so competent, so resilient, whereas I …

The room seemed to wobble and then fade, and then come into focus again. And for the next hour, Kate and Sam and I revelled in our memories, in the shared language of our childhood, finishing one another’s sentences, speaking in a code that must have bewildered Moodie and Mr. Traill, who listened in amused silence and then finally took the children to their beds, leaving my sister, my brother and me to our talk and laughter until I thought I might pass out from happiness.

~~~

Excerpt from The Lost Diaries of Susanna Moodie by Cecily Ross ©2017. HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved.

More Info

Cecily Ross will be a guest author at Words in the Woods, the Dunedin Literary Festival, on September 9. For details, see Must Do section.

Related Stories

How a Horse Helped Mend a Broken Heart

Mar 21, 2006 | | Back IssuesFor some reason, Basil, who is a naturally cautious if not fearful person, is not afraid of horses.

Memoirs of a Caledon Pioneer

Nov 15, 2007 | | Historic HillsAfter the ox cart driver bid farewell and left us, and I began to clear away the snow where we were to lay our bed.

Shadows in the Forest

Nov 22, 2016 | | Historic HillsMany a table regularly offered squirrels, groundhogs and, of course, ducks and geese.

Where the Wild Things Are

Nov 8, 2014 | | Notes from the WildWhere brook trout flourish, expect other exquisite wild things.

Clara Brett Martin: Canada’s First Woman Lawyer

Mar 21, 2009 | | HeritageA Modest pioneer, Clara Brett Martin, the daughter of a Mono Township pioneer family, became a pioneer of a different sort when she challenged the Law Society of Upper Canada to become the first woman lawyer in the British Empire.